Forty Years of the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival

From the drone blasts of Polwechsel to Pauline Oliveros's ecological politics, deep listening at the festival’s anniversary edition

From the drone blasts of Polwechsel to Pauline Oliveros's ecological politics, deep listening at the festival’s anniversary edition

Friday 13 October 1978. As thick banks of winter fog descended on northern Europe, the doors of Huddersfield’s town hall – a high-vaulted, Victorian box in that mix of austere sobriety and baroque ornament peculiar to public entertainment palaces of the time – opened and a new festival of contemporary music began. The first concert started strangely, with music by the 19th century composer-pianist Franz Liszt; but ended with a bona fide 20th century masterpiece, Iannis Xenakis’s Eonta (1964) for piano and brass quintet.

Yet the festival’s start date proved inauspicious. That fog stranded several performers at airports in Europe and replacements had to be found at short notice. The carefully themed programme was ruined. Nevertheless, when the festival closed five days later, with a performance by the pioneering quartet Warsztat Muzyczny (Music Workshop) from Warsaw, it could be judged a qualified success.

The Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (HCMF), as it was christened, and which has just celebrated its 40th edition, was founded at a time when regional arts funding was at its height. It was the brainchild of Richard Phillips, music officer of Yorkshire Arts Association. Having recently toured a number of European music festivals, Phillips decided that Yorkshire needed its own. In fact, it needed two: an early music festival for the medieval city of York, and a new music festival, for which Huddersfield, a city whose polytechnic had a thriving School of Music specializing in the 20th century, was chosen as host. Richard Steinitz, a composer and lecturer at Huddersfield polytechnic, became the festival’s director, a role he held until 2001. Both festivals were constituted in a remarkable two-year period of civic altruism that also saw the establishment of the Yorkshire Sculpture Park near Wakefield and Opera North, in Leeds.

In subsequent years, Huddersfield’s festival moved to an even darker and damper week in mid-November, but the weather has never slowed its ambition. It is a cliché to say, but a small post-industrial town in West Yorkshire, on the brink of winter, is an odd time and place for one of new music’s annual pilgrimages. (One composer noted on Facebook that Huddersfield’s first snow of the year always falls during HCMF week. This year was no exception.) And yet it draws listeners year on year; and they come from the local area as much as from London or mainland Europe.

As we all do as we approach 40, there was a certain amount of self-reflection and recollection in this year’s programme. If the London Sinfonietta’s concert – a sit-down event of conventionally notated works, two of them more than 30 years old – seemed anachronistic in context, it could be excused on these grounds. Indeed, its two old-school modernist slabs, Xenakis’s Thallein (1984) and Harrison Birtwistle’s Silbury Air (1977) were both works the Sinfonietta (itself in its 50th year) had commissioned and, moreover, were by two composers with Huddersfield associations dating back to the festival’s earliest days – Birtwistle was one of the first major composers to attend, and Xenakis the first to have a full day devoted to his music (in 1982).

Read: Andrew Mellor on 50 years of the London Sinfonietta

But, it has to be said, the Sinfonietta are part of HCMF’s history more than its present. When HCMF was founded, ‘contemporary music’ still very much meant composed works in the classical tradition – written down and given to performers to realize. Electronic music, performance art, music theatre and even free improvisation were all active forms, and all featured to a greater or lesser degree at the festivals of the 1980s and ’90s, yet Steinitz’s primary interest remained composition, and this is where the festival’s focus was trained. When the festival was handed to its current director, Graham McKenzie, in 2006 (after short spells under the direction of Susanna Eastburn and Tom Service after Steinitz’s retirement), that focus shifted noticeably. McKenzie came to Huddersfield from Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts, where he had programmed music alongside the visual arts, commissioning new works and inviting internationally renowned musicians.

Steinitz, writing in his history of HCMF’s first 33 years – the sumptuously illustrated Explosions in November (2011) – acknowledges that McKenzie’s appointment ‘signalled a more decisive change of direction … Graham brought an enthusiasm for visual and experimental work and multidisciplinary practice across genres’. Non-traditional concert spaces, multimedia, installations, performance art, electronica and improvisation all moved from the festival’s edges to its centre, on an equal footing with its traditional core of notated music. In this it is reflecting the practice of many European festivals today – such as Borealis in Bergen, Gaudeamus Muziekweek in Utrecht, MaerzMusik in Berlin and Ultima in Oslo – but doing so on a scale (almost 40 events over 10 days) that few of them can match.

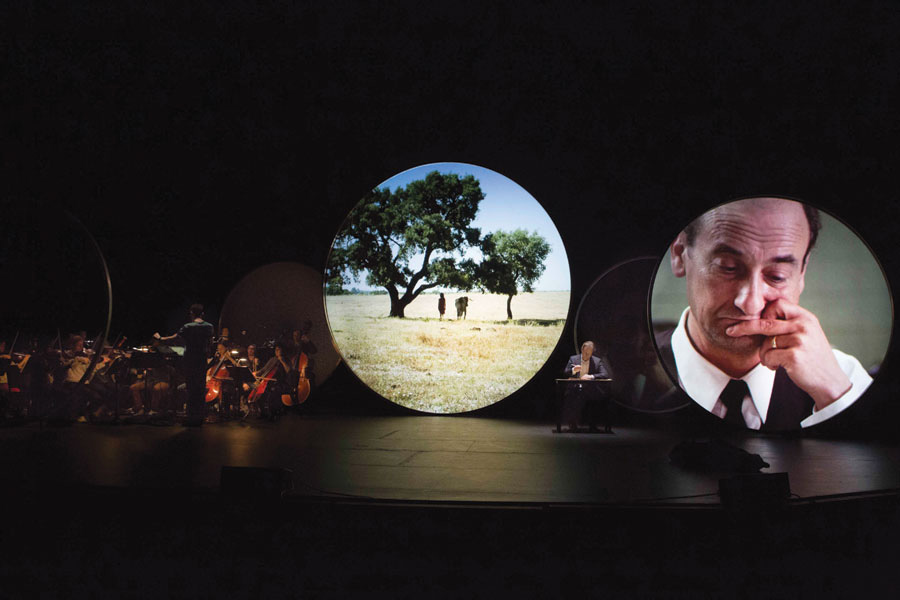

Improvisation in particular has been among McKenzie’s strengths. Real-time composition was never wholly absent from previous years (the list of musicians who played in the pre-McKenzie era includes Anthony Braxton, Barry Guy, Evan Parker and Terry Riley), but McKenzie turned serious attention beyond notated music for the first time. His first few festivals included performances by (among others) John Butcher, Rhodri Davies, Axel Dörner, Frances-Marie Uitti, the Simon Fell Ensemble and Evan Parker’s Electroacoustic Ensemble. This year saw returns by Butcher and Davies (the former reunited with his old group Polwechsel in a devastating 70-minute blast of drones and percussive agility that also featured Austrian composer Klaus Lang firing up the rarely used St Paul’s Hall organ), as well as a trio of Michaela Grill, Philip Jeck and Karl Lemieux; Nik Bartsch’s MOBILE; the noise-cum-Americana duo Archer Spade (trombonist Dan Blacksberg and guitarist Nick Millevol); and the folk-inspired violin and recorder drones of Laura Cannell.

Another thread was that of realizations or reconstructions. Berlin’s zeitkratzer ensemble performed their acoustic arrangements of early Kraftwerk tracks; in a second concert they were joined by Ensemble 2e2m from France for their renowned realization of Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music (1975). Elsewhere, the 60th anniversary of the now defunct Polish Radio Electronic Studio was celebrated in concerts by Thomas Lehn and Valerio Tricoli that reconstructed (and in the latter case reimagined) music by two pioneers of electronic music in Cold War Poland, Bogusław Schaeffer and Bohdan Mazurek.

For all this, the greatest sense of occasion was still attached to the most conventional moments in the festival’s ten days: Big Works by Big Names. Brian Ferneyhough’s deeply moving Umbrations (2017), played by Frankfurt-based Ensemble Modern and the evergreen London-based Arditti Quartet, was an apparent farewell to composition by an ageing master; James Dillon’s Tanz/haus (2017), another festival commission, was the latest major contribution from an HCMF regular (and winner of a Young Composer Award at the 1978 festival) – it was played by Scotland-based Red Note Ensemble. Other notated music specialists, among them the Montreal-based Bozzini String Quartet (playing music by the wonderful Canadian composer Linda Catlin Smith), Ensemble Grizzana, led by the Swedish composer Magnus Granberg, the Swiss/German/Israeli/American Ensemble Nikel and London’s Riot Ensemble (of whose artistic board I am a member) also made strong impressions.

The death of the great American experimentalist Pauline Oliveros coincided with last year’s festival, and this year she was remembered in several events, including the UK premiere of her 75-minute Primordial/Lift (1998), played by members of New York’s ICE and Manchester’s Distractfold. A grand expression of Oliveros’s ecological politics and her philosophy of ‘deep listening’, it was structured around a low frequency oscillation that rose from 7.8Hz to 13Hz (below the threshold of human hearing, which bottoms out at around 20Hz), matching a shift in the earth’s own electromagnetic resonance that the new age author Gregg Braden projected would take place between 1960 and 2010, and precipitate the reversal of the earth’s magnetic poles.

It was a beautiful experience. Oliveros’s own low frequency oscillator had been shipped over for the occasion, so she was in a sense still present. Her partner, the writer IONE, introduced the work, and the evening had a sense of commemoration and celebration. Among the few lines in the score is the instruction to play something, then listen, then play something else, and the music produced by this gentle guidance was sparse in texture but rich in aura – an invisible net of connecting threads. Another chilly night in Huddersfield’s venerable town hall, another little bit of new music magic.

Main image: Polwechsel in rehearsal. Courtesy: Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival; photograph: Graham Hardy