Captain Russia

In this series, frieze d/e looks at the logistics behind art works. Here, Isa Rosenberger explains the film she made for an exhibition aboard a nuclear-powered icebreaker in Murmansk

In this series, frieze d/e looks at the logistics behind art works. Here, Isa Rosenberger explains the film she made for an exhibition aboard a nuclear-powered icebreaker in Murmansk

At the end of 2012, I received an invitation to be part of Lenin: Icebreaker, an exhibition aboard the nuclear-powered icebreaker ‘Lenin’ in Murmansk. I had just begun a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program in New York. This put me in the absurd situation of being an Austrian in New York working on a project at the north-western tip of Russia. But I knew that invitations like these – to contribute to a project that is ‘crazy’ in the best possible sense – don’t come twice, and that I would accept, come what may.

Austria’s cultural attaché in Moscow, Simon Mraz, curated the exhibition with Stella Rollig from LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz as part of the 5th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art. A number of Russian and Austrian artists were invited to engage with the legendary vessel: the world’s first nuclear-powered icebreaker and once a celebrated symbol of Soviet progress, the ‘Lenin’ is now a museum anchored in Murmansk.

Faced with this impressive ship, which in itself already represents something akin to a Soviet total art work and which is already so politically loaded, it was a challenge to develop a work that would not be overpowered by the location. In February, I flew from New York for a visit – an extremely eventful trip that reminded me of a Cold War thriller. In the ship’s canteen, I noticed a projection screen, the room having doubled as a cinema. This gave me the idea of reactivating the screen, with a video work dealing with the Cold War and – like most of my films – combining documentation, fiction, staging and performative elements.

Initially, I wanted to ask passers-by in New York and Moscow about their memories of the Cold War. This proved difficult logistically, however, both in terms of budget and time. So I decided to concentrate on Russian immigrants to New York whose life stories were written by the Cold War. But when I raised the topic with older people at Brighton Beach in southern Brooklyn – also known as ‘Little Russia’ – things did not go smoothly: even after years in the United States, many of them still only speak Russian, which I do not. Added to which a certain mistrust arose as soon as the Cold War was mentioned. Finally I found the Knesset Adult Day Care Center, where my idea was very openly received. There I met Vladimir K., 83 years old and full of energy. For many years, he was a captain in the merchant navy of the former Soviet Union. He has been living in the United States since 2000.

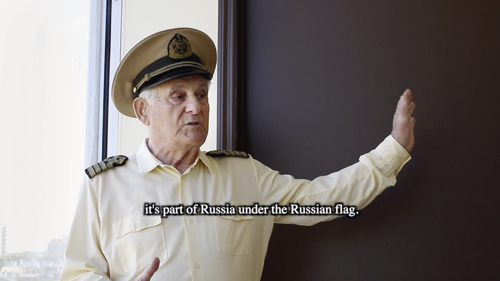

Meeting Vladimir proved to be a stroke of luck. His biography brings together many different issues and evokes diverse images of travel: between continents, between historical periods, between political systems and ideologies. Vladimir’s talent as a performer, his enjoyment of being in front of the camera, and his nuanced way of speaking about history (and his place within it) gave me further reasons to make him the central character in my film.

Over several weeks, I interviewed him extensively with the help of an interpreter and we shot a number of scenes on Brighton Beach, some of them staged. There was no film crew, just me and my video camera. One day, Vladimir turned up in his captain’s uniform, producing some great footage: in his original Soviet-era outfit, the captain proudly strode along the seafront promenade as passersby stopped to look at him with a mixture of disbelief and reverence.

The resulting film, Wladimirs Reise (Vladimir’s Journey, 2013), opens with a fictitious scenario: Nikita S. Khrushchev and Richard Nixon meet in the afterlife and are obliged to continue their legendary ‘Kitchen Debate’ of 1959 for all eternity. (The Soviet premier and the then US vice president held this improvised debate on the relative merits of communism and capitalism in front of television cameras at the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959.)

Historical archive material serves as an important point of reference in my film, connecting different levels, places and periods. My thinking was that the ghosts of the past pursue us into the present as undead revenants. The current confrontations between the United States and Russia increasingly remind me of the rhetoric of the Cold War, even if conditions today are entirely different. In this context, I was also interested to read Jacques Derrida’s Specters of Marx (1993; 1994), from which I borrowed a quote for my video: ‘And this being-with specters would also be, not only but also, a politics of memory, of inheritance, and of generations.’

To achieve a ghostly effect, I reproduced the original colour footage of the ‘Kitchen Debate’ in black and white, in negative. As I could only find a low-resolution copy of the original, the sound is not great, but that doesn’t bother me as it makes the clash between the two politicians sound even more ghostly. In the course of my research, I also happened across a television clip showing Nixon during his Soviet trip of 1959 visiting the ‘Lenin’, then anchored in Leningrad. In front of the icebreaker’s crew, he gave a brief but highly dramatic speech that I show during the opening credits: ‘The Soviet Union and the State of Alaska are only 40 miles apart. Very little ice for the powerful Lenin. The two nations must work together to break the ice between them!’

I think the scenes in the film where I ask Vladimir K. about his memories of the ‘Kitchen Debate’ give a particularly good sense of what mainly interests me: how alternative versions of the past and present can be obtained from a confrontation between personal memory and canonical history. Among other things, Vladimir says: ‘This meeting was a historical event, and it doesn’t matter that Nixon had eavesdropped … I remember it very clearly: What they said didn’t only not apply to Russia, but it didn’t apply to the Americans either.’ One scene I find especially striking is where Vladimir, although he only really speaks Russian, casually comments in English on the debate between Khrushchev and Nixon: ‘It’s PR!’

Unfortunately, Vladimir was unable to attend the exhibition opening in Murmansk in September – at 83, the journey would have been too strenuous. But the Knesset Adult Day Care Center also has a projection screen, and the film was shown there in October. And next year, the exhibition (sadly without the ship) will be coming to the Austrian Cultural Forum in New York – where Vladimir will be my guest of honour.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell