Ger van Elk

Lüttgenmeijer, Berlin, Germany

Lüttgenmeijer, Berlin, Germany

The image of a horizon is one of the most primal and insistent of pictorial motifs. Incontrovertibly grand but also suggestive of cynical perfunctoriness, it is an ideal device for painters who wish to treat figuration with scepticism. It allowed Mark Rothko, for example, in his late acrylics known as ‘The Black Paintings’ (1968–9) to produce what are arguably his flattest and most abstract works, while having them clinch the sublimity of deep pictorial perspective out of a process that does everything to call such sublimity into question.

The Dutch artist Ger van Elk, now in his 70s, emerged in the late 1960s among a generation of early conceptual artists intent on rejecting painting’s hegemony. But he has always maintained a close relationship to the Western painting tradition, using photography to meditate upon it. In 1979, he created a series of small landscape photographs placed in sequence on a brass shelf. The horizon line was relayed from one photograph to the next, like a minimalist axiom subverting the illusionism of its constituent images. Two decades later, he installed a series of 17th-century Dutch landscape paintings upside-down and side-by-side, so the horizon line, running from one to the other, appeared as a geometric generalization traversing the individual pictures, and weakening the autonomy of their record.

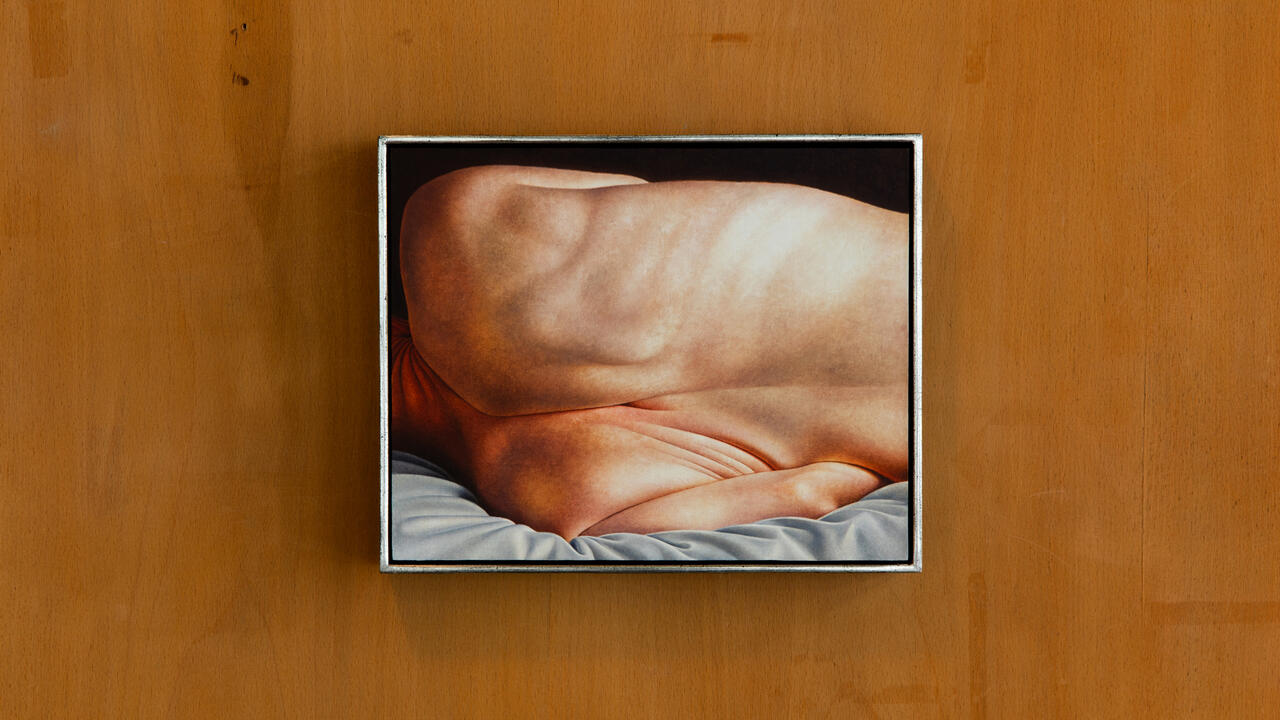

Photography and painting were also fused in the one earlier work in Van Elk’s recent solo exhibition at Lüttgenmeijer, titled ‘Sieben Automatische Landschaften’ (Seven Automatic Landscapes). This work, View of Kinselmeer (1998), is a narrow, horizontal photograph of a seascape, retouched with paint then re-photographed and divided into two sections corresponding to sea and sky, which face the viewer at slightly divergent angles from one another. The gesture reflects Van Elk’s doubt in, and even denial of, the original image – manifested by its filtering through paint, its bisection, the disruption of its single flat plane, and the reflective coating of its glossy Cibachrome, obscuring transparency. But his implication is that the horizontal landscape is so powerful a format it can withstand such deconstruction while maintaining its illusionism.

Van Elk’s new installation, Sieben Automatische Landschaften (2013), dispensed with both paint and photography, but comprehended both, and managed to distil all of the artist’s earlier landscape conceits into a more concise form. Van Elk filled seven rectangular glass containers, each three centimetres wide and two centimetres high, with equal amounts of oil and water – tinted different colours – and then encased each one in a larger rectangle of clear Perspex, 15cm x 10cm, like a passe-partout frame. Oil surmounts water, creating two almost equal zones. The use of dyes might invoke watercolour painting, a mainstay of the genre of landscape painting, but the objects themselves – their miniature scale, pristine surfaces, sour colours and hard-edged frames – evoke a Polaroid. The various combinations of colours made the installation a spectrum, with each landscape – hooked to the wall at head-height – confirming the others’ horizon lines, while distinguishing itself from them. But the individual ‘landscapes’ were hung far enough apart that their pictorial autonomy ultimately predominated over their submission to the overriding abstraction of the ‘horizon’ they shared. They could also be seen as modest physics experiments, discovering that oil rises above water, and does not mix with it, and that the objects could not be made any smaller without the capillary effect inducing a more emphatic curve to the juncture between oil and water, disrupting the flatness of the ‘horizons’.

This fastidious empiricism contrasts with the installation’s romantic nostalgia for the painterly vignette and, more specifically, for the great Dutch tradition of landscape painting. Sieben Automatische Landschaften remind us of paintings of Dutch flatlands by 17th-century artists such as Philips Koninck. Each one can be seen as representing a particular set of conditions: cobalt oil over khaki water, a clear dusk; pale blue over brown water, early morning; orange over mustard, a blazing sunset. But in Van Elk’s radical reduction of such sentiments to the smallest, most oblique vehicle imaginable, there is a pervasive sense of the absurdity and futility of the sublime landscape genre. The irony is all in his use of that adjective ‘automatic’, implying both the inevitability of a cliché, and the reliability of the viewer's susceptibility to it. Such irony tends to establish itself unequivocally, disqualifying any position which dares to dream; but here it is held in check by Van Elk’s yearning for the continuing possibility of pictorial illusion, as the liquid ‘landscapes’ are sealed within their Perspex frames.