Gianfranco Pardi

Giò Marconi, Milan, Italy

Giò Marconi, Milan, Italy

Gianfranco Pardi cannot have slept much in 1973, judging by the amount of work he produced that year. That prolificacy would perhaps be unremarkable, were it not for the works’ unerring consistency and precision. The relentlessly laconic titles – nearly every object from this period bears the designation ‘Architecture’ – obscures a variety of materials (buffed metal, steel, wood, aluminium, acrylic on canvas) and format (pyramidal, trapezoidal, vertical and horizontal). The majority of the works, however, are simply rectangular. Their geometric variation is an interiorized one, effected both on the canvas’s surface (as drawn grids or diamond-shaped reticulations) and in front of it (in the form of tensed cables or metal plates). Sometimes the dialectic between painting and sculpture takes place within individual pieces, which combine painting with other materials; at other times the pictorial aspect is emptied out in favour of a more emphatically sculptural presence.

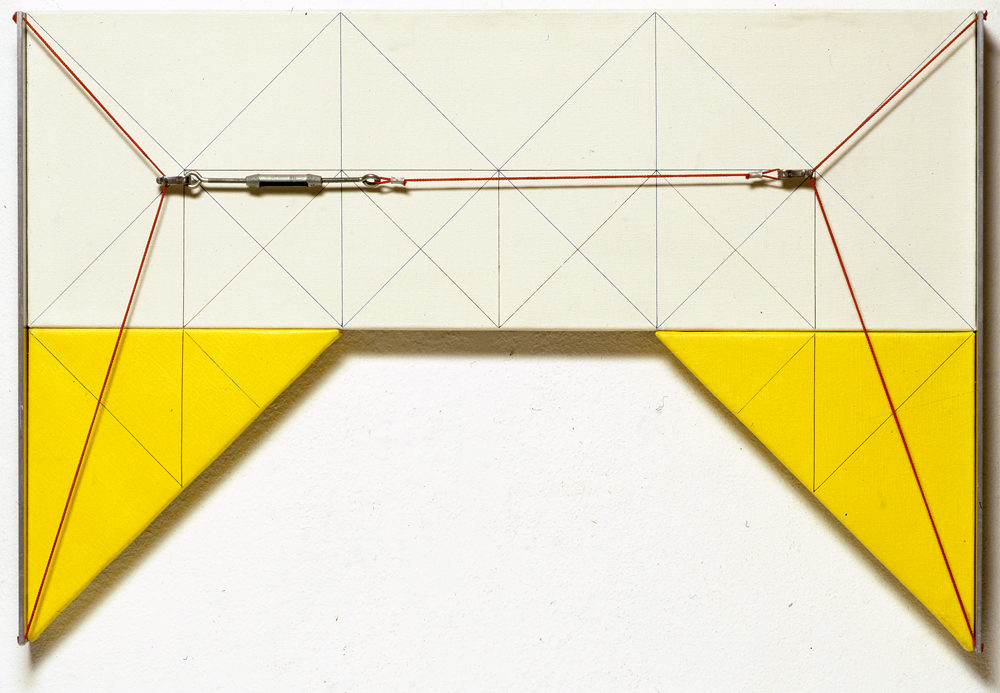

Often a steel or nylon cable is threaded through and over the canvas’ frame but is duly tucked back inside its borders, criss-crossing symmetrically or slightly off-kilter. Some of the works bear aluminium plates, cut to square and suspended atop their surface by the ever-present cables. In one work from 1975 the plates are centred; in another contemporaneous piece they are moved to the upper and lower portions of the canvas, cables threaded between them in a dance of diamonds and triangles. Each work plays out a shifting conversation between the canvas’ painted, acrylic surface – refined, tight-lipped, delicate – and the acrobatics of its tensed cables. Even in their humility these conversations are absorbing.

The geometric rigour and frank materialism of Pardi’s work evokes the legacy of Russian Constructivism, particularly its ‘productivist’ phase, when objects aimed at some future use-value. (The title of one work from 1973, Proun, is a direct nod to the eponymous series of works by El Lissitzky of 1919–23, suggesting this affinity was not lost on Pardi). Of course, Pardi’s works do not pledge any practical application. Their designation as architecture is purely nominal. Even the apparent functionality of a bracketed column of riveted and painted aluminium from 1972 appears alienated from any structural function. But his project returns us to the Constructivists’ adventurous exploration of materials, although it is tamed by an almost arithmetical sobriety (reminiscent, in turn, of De Stijl).

In that respect Pardi’s canvases are also reminiscent of Frank Stella’s ‘black paintings’, most notably Die Fahne Hoch! (The Flag On High, 1959), in terms of the lines’ immanence to surfaces and boundaries, calling attention to the work’s support. The ever-present cables (and their prominent joints) alternately hyperbolize and distract from that attention. In some works the trajectory of the cables diverges from the lines traced underneath; in others they square almost exactly with the fastidious itinerary of the canvas grids.

The effect of the juxtaposition between these drawn grids and the literalness of the cables’ physics is hard to pin down. Do the cables complement the neat geometry of the painting? Or do they flout it? Do they reinforce the works’ pictorial (and essentially flat) formal concerns, or do they interrupt them, insist on the canvas as an object? They might be said to stir a double consciousness in the viewer, vacillating between objecthood and opticality (perhaps even ‘literalism’ and ‘grace,’ to rehearse terms that haunted Stella’s reception across the Atlantic). Ultimately, however, the cables’ bulbous clamps and slender shadows underscore their exteriority even when they appear in concert with the temporal and spatial dimensions of the canvas’ surface.

These formal concerns conceal – perhaps hide in plain sight – Pardi’s philosophical and literary sympathies with, among others, Friedrich Nietzsche, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Martin Heidegger. Such sympathies were most evident in the exhibition’s final room, featuring Pardi’s installation Poetically Man Dwells (1977) – its title borrowed from an essay by Heidegger, itself lifted from a line by Friedrich Hölderlin. It re-creates three doors (one of them solid, the other two pierced with several slats) from one wall of the house in Vienna that Wittgenstein designed for his sister. The installation was originally mounted in 1978 in the Studio Marconi, run by Giò’s father, Gino Marconi, himself a famed Milanese gallerist who in the 1970s helped launch the careers of several notable artists. Along with photographs of that original installation numerous preparatory studies – cardboard maquettes, drawings and perspectival renderings – offered a reconstructive archaeology of Pardi’s (deceptively spare) final objects. The artist himself calls them ‘flawed approximations of a possible logical framework for defining the wall’s space and its ratios’. This ascetic ratiocination cannot obscure Pardi’s fundamentally lyrical concern with geometry, in both its earthly manifestations and its metaphysical resonances. His work constitutes a major achievement in the history of Italian abstraction. This show did much to flesh out the dimensions of that achievement.