Henry Fuseli’s ‘The Nightmare’ Makes Terror Erotic

Why is female fear often conflated with desire?

Why is female fear often conflated with desire?

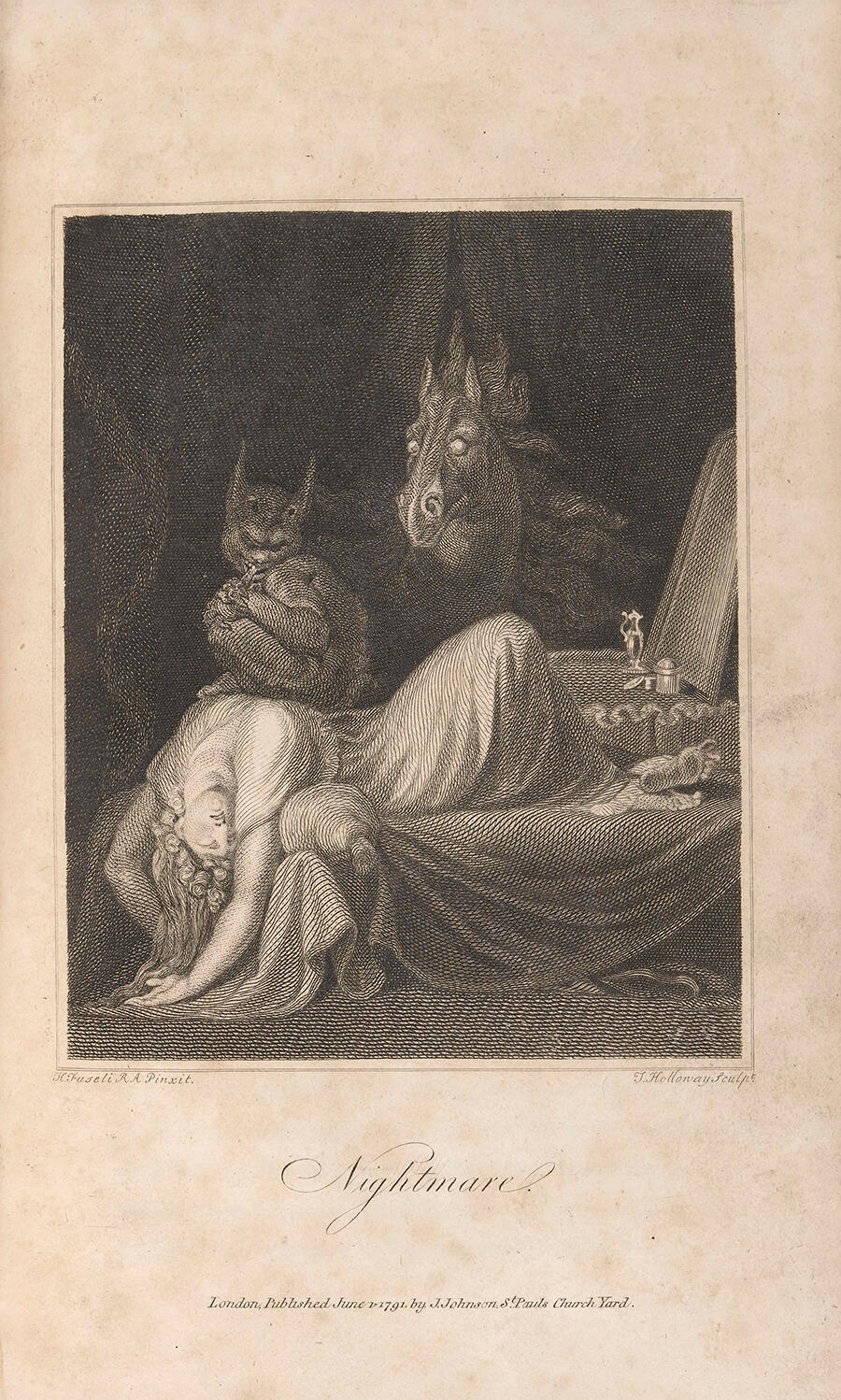

A sleeping woman contorts her body on a chaise. A gargoyle crouches on her stomach. A mare’s eyes glow in the darkness, its head casting a devilish shadow on a crimson curtain.

When I first saw a reproduction of Henry Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare (1781) in secondary school, I experienced anew a sensation I’d never previously encountered translated into words or images. Since my childhood fever dreams, I’d occasionally perceived another force – a person’s body – visiting me in my sleep, squashing me, stopping me from waking. Even though my mind was conscious, my body was paralysed in the darkness. I would feel the force pushing and pulling on my limbs. Sometimes, it would lift and twist me, stretch me in the air, drive me down a racing track. Sometimes, it would stand at the end of my bed, confronting me with shadowy half-visions. I would try to tear myself out of it, rap my fist on something – anything real – as a wake-up signal. But the malevolent force kept pulling me down.

When I finally managed to wake, heart pounding, switching on the light, the shadows lingered, the room felt alien. Panic would strike: the swelling of my hands and tongue a sign of the oncoming bodily separation. Then, I would feel myself sinking into sleep once more, unable to move, the force creeping up my jaw. It was going to start all over again.

When The Nightmare was first exhibited at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition in London in 1782, it ‘excited … an uncommon degree of interest’, according to the artist’s biographer, John Knowles, in The Life and Writings of Henri Fuseli (1831). The subject matter was entirely unprecedented but won enduring fame, with artists, writers, printmakers and publishers producing countless reproductions and interpretations of the work.

The woman’s suggestive pose, with her back arched almost to a right angle, has invited various speculations as to the work’s underlying symbolism. In Eros in the Mind’s Eye (1986), Donald Palumbo argues that the woman’s position was one then deemed to encourage nightmares, that Fuseli wished to imply that she was willing the haunting. Meanwhile, in his History of Art (1962), H.W. Janson focuses on her perceived sexual receptivity, arguing that she represents the artist’s beloved, with Fuseli identifying as the incubus. This confusion of female fear with female desire makes the work all the more disturbing.

Now, when I look at this painting and remember giving myself away to a dark force in the night, I wonder who was the guilty party: me or it?

Main image: Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781, oil on canvas, 101 × 127 cm. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons/Detroit Institute of Art