The Horrifying Beauty of Dana Schutz’s Paintings

At Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, the New York artist renders grotesque iconography with deeply unsettling results

At Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, the New York artist renders grotesque iconography with deeply unsettling results

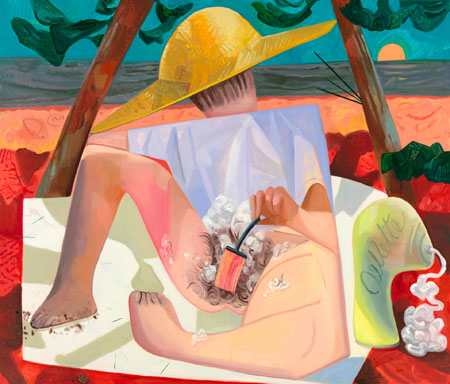

Dana Schutz renders grotesque iconography with painterly virtuosity. In her solo exhibition at Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal – her first in a Canadian museum – 24 paintings completed over the last 15 years feature deformed faces and contorted bodies that draw on Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection, with deeply unsettling results.

The figure struggling acrobatically to put on clothing in Getting Dressed All at Once (2012) is less illustrative of a department store shopper than of Schutz herself, given the painter’s messy and improvisatory relationship to her chosen medium. There is a punchy dynamism to Schutz’s paintings, and an inherent instability that one assumes she must work hard to achieve, but which nevertheless appears effortless. Her bold palette, animated formal compositions and riffs on 20th-century painting (subtle and not-so-subtle allusions to synthetic cubism and Czech surrealism) give these paintings a commanding presence.

Schutz finds precedents in the works of fellow painters Maria Lassnig and Marlene Dumas, but her work is her own signature brand of in-your-face American Pie. Its pastry dough could be courtesy of Philip Guston: Schutz’s piping hot colours and whipped cream-like impasto are reminiscent of Guston’s late pink paintings. Wonderfully thick excrescences in their surfaces remind the viewer of the medium’s material nature. Paint is Schutz’s fundament.

At MACM, the paintings’ subjects are morphologically grotesque, though their deformations never feel gratuitous. Their uncertain forms echo Kristeva’s declaration in Powers of Horror (1982) that ‘Abjection is, above, all, ambiguity.’ Schutz’s transgressively ambiguous play with painting styles lends her figures their own sense of physical instability: in Sneeze (2001), for example, the snot that issues from a figure’s nose – more like a pig’s snout than a human’s – is painted with an exuberant splash of pigment. In other paintings on view, the ground shifts uncertainly beneath the figures’ feet, imparting an uneasy feeling of vertigo. Schutz’s subjects move in what always seems to be the wrong direction. Painted at high chromatic temperatures, their contorted bodies appear malleable, like melted plastic.

Many paintings openly provoke visceral disgust. In Face Eater (2004), for instance, a human figure tries to consume itself whole. Other bodies appear plagued by flesh-eating bacteria, mutations caused by nuclear radiation, and other anatomical abnormalities. In other paintings the horror is more indirect: the blindfolded men in suits in Men’s Retreat (2005) recall trigger-happy former American Vice President Dick Cheney on a hunting party, or the murderous Elite Hunting Club in the cult slasher flick Hostel (2005).

Schutz’s horrifying and anamorphic paintings are loosely based on what she calls ‘metanarratives’, which regard the grand narratives of history painting with more than a little suspicion. Google and Boy With Bubble (both 2015) slip in and out of pictorial genres like wily shape-shifters. Schutz describes their subjects as ‘composed and decomposing, formed and formless, inanimate and alive’. For this painter, the genre of painting – and reality itself – is endlessly pliable.

Schutz’s work can be aggressively ugly but never lowbrow. She reminds us that ‘beauty’ is not synonymous with mere attractiveness and that ugliness does not always elicit revulsion. Ugliness challenges us by upsetting our presumptions about appearances. One of the most crowd-pleasing pictures in London’s National Gallery is Quentin Matsys’s The Ugly Duchess (A Grotesque Old Woman) (1513), which depicts a royal sitter suffering from Paget’s bone disease, which cause horrible facial deformities that seemingly afflict Schutz’s fearsome Face Eaters. Schutz’s grotesquerie seduces with its ugliness. Indeed, what seems grotesque on the surface pulses beneath with a strangely compelling and singular beauty.