How are Algorithms Changing the Way Art is Seen?

Jörg Heiser on the Soviet sci-fi classic Planeta Pur, algorithmic bias and the limits of artificial intelligence

Jörg Heiser on the Soviet sci-fi classic Planeta Pur, algorithmic bias and the limits of artificial intelligence

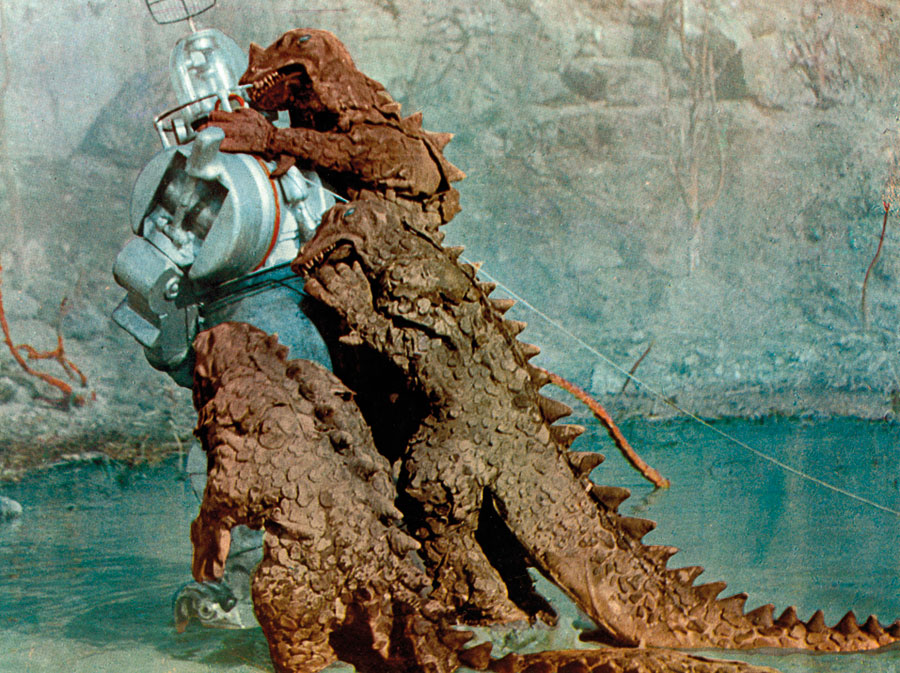

In the Soviet sci-fi classic Planeta Bur (Planet of Storms, 1962), a robot accompanies cosmonauts on a mission to Venus. His name is not Alexei or Ivan but John, and he attempts to save two of the scientists exploring the planet’s surface, carrying them across a lava stream. Yet, halfway through, John announces that, because of the heat, carrying the load any further would be hazardous to his mechanics. The scientists try to turn off his self-protection program – a switch on the robot’s back. Their attempts to do so cause John to malfunction, and he starts to play American big-band jazz like a jukebox. The two are eventually rescued by their comrades.

The message is clear: Western capitalism may produce superior technology, but its ethics tend towards egotism and cruelty; socialist comradeship will win. We know it didn’t, but that doesn’t undermine John’s warning. What need to be kept in check today are not just speaking tin cans with arms and legs but algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) – the invisible operators hidden in the depths of our networked world. The former hedge-fund analyst and big-data expert Cathy O’Neil describes these, in the title of her recent book, as Weapons of Math Destruction (2016). What she has seen in both finance and IT, she writes, is a ‘widespread use of imperfect models, self-serving definitions of success and growing feedback loops’, leading to algorithms that amplify social inequality or reinforce sexism and racism. For example, a Google AI designed to police online comments rated ‘I am a gay black woman’ 87 percent toxic compared to 20 percent for ‘I am a man’.

Algorithmic biases leading to crass discrimination or even deaths – as in the case of a Pentagon operation that underestimated the number of civilian casualties of anti-ISIS airstrikes in Iraq by a staggering factor of 31 – are not just technical defects: they are based on human prejudice. Against that background, asking about the effects of algorithms on the art world seems negligible. But art is not isolated from everything else. News-feed algorithms favouring populist vitriol for its click-bait quality have had comparable effects on debates around art. Museum scandals, calls to close exhibitions and to destroy or remove artworks – which are quick to draw parallels with Nazi censorship – are sure to gain online traction instantly, dividing the public sharply into opposing camps. Attempts to discuss complication and nuance, or what we actually see in an artwork, are trolled or buried under heaps of self-righteous, often slanderous rhetoric.

Hence, how handy it is that seeing, processing and creating images can now be delegated to AI. Google’s Art & Culture app has made the rounds with its novelty effect of pairing faces with museum paintings, matching ginger-haired art critics from Germany with portraits of 17th-century Dutch gentlemen – while a colleague of African descent may be twinned with casually racist depictions of servants and slaves. Last year, researchers from Rutgers University collaborated with Facebook to devise an AI that generated new imagery from more than 80,000 paintings from the 15th to the 20th centuries. Hired as evaluators, people working for Amazon’s Mechanical Turk – a crowdsourcing marketplace that brokers human intelligence – predominantly interpreted these images as handmade. According to one of the researchers, the AI was programmed to make something with ‘arousal potential’ so that it wouldn’t be ‘considered boring’, something ‘novel, but not too novel’. In other words, the machine produced what a second-rate, market-conforming artist would make – mildly quirky abstractions, in this case. And those who evaluated them did not necessarily have an interest in art, much less a serious commitment to it. There seems to be an algorithmic bias against imagination at work, and against serious engagement.

So, what to do? Compliance to ethical standards needs to be established in IT companies and AI conception should not be left exclusively to programmer geeks. Even more importantly, the three laws of robotics devised by sci-fi writer Isaac Asimov must be put into practice, politically and juridically. First introduced in the 1940s, they state that robots must not harm humans, that they must obey humans (unless it would break the first rule), and that they must protect their own existence – provided there is no conflict with laws one and two. John, in Planeta Bur, broke all three. Equally, an algorithmic bias could be read as harmful to humans, while its mechanics usually remain hidden. Marc Rotenberg, a US law professor, therefore suggests adding two more laws: the fourth, under which a robot must be able to identify itself to the public, and the fifth, under which a robot must be able to explain its decision-making process. In other words, no more secret codes and no more AIs whose actions aren’t even understood by their programmers. Art can afford to be ambivalent, even mysterious; science and technology can’t.

This article appears in the issue 194 April 2018 print edition, with the title Artificial Stupidity.