How Artist Bruce Nauman Plays at the Edges of the Human

A retrospective survey at MoMA and MoMA PS1, New York, considers how Nauman stretches language, to demonstrate how it, in turn, moulds us

A retrospective survey at MoMA and MoMA PS1, New York, considers how Nauman stretches language, to demonstrate how it, in turn, moulds us

‘My work’, Bruce Nauman told Art in America in 1988, ‘comes out of being frustrated about the human condition.’ Black radical aesthetics and criticism prefigured my encounter with ‘Disappearing Acts’, the artist’s retrospective survey at the Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1 in New York, which was first mounted at The Schaulager last summer in Basel. For me, ‘withdrawal as an art form’ – to use the show’s description of Nauman’s work – calls to mind fugitivity. Black critical thought is a critique of the human as a condition of unfreedom. What is life without (such) conditions? The human is a border concept – some are in, while others are barred from the fold. Nauman plays at the edges of the human, blurring and fraying its conceptual boundaries. These topics are crucial for our current catastrophic moment and the human-as-border concept undergirds the current wave of global fascism, ecological disaster, late-stage racial capitalism and sovereignty’s signature walls and cages.

‘Disappearing Acts’ is awe inspiring in its magnitude and scope. At MoMA PS1, where a sizable chunk of the show occupies the museum’s three floors, expansive rooms allow for full immersion in Nauman’s large installations and sculpture from across his six-decade career. Coupled with the sixth floor at MoMA, the exhibition presents an artist of enormous technical and aesthetic complexity. In one particularly representative chalk and graphite drawing, My Last Name Extended Vertically Fourteen Times (1967), Nauman’s surname is stretched into a kind of seismograph that causes you to disentangle the letters slowly. This process not only disfigures his name (now so emblematic of artistic dexterity in the second half of the 20th century), but our own cognitive and linguistic schemas in a discursive torsion that twists language’s familiarity and the presumed universal nature of grammar and its visual representation. As Ludwig Wittgenstein writes in Philosophical Investigations (1953): ‘For philosophical problems arise when language “goes on holiday”.’ Throughout this wide-ranging retrospective, Nauman stretches language, makes both its games and its form plastic, in order to show how it, in turn, moulds us.

Much of Nauman’s work considers those holidays of meaning. For his astonishing seven-channel, 3D video installation Contrapposto Studies, i through vii (2015/16), Nauman plays off Greek classic sculptural positionality. Two rows of seven channels show the artist in a plain room, with the videos on the top screened in inverse colour to those on the bottom. Here, his body – shot just below the chin – is slanted and skewed in its gait, and he moves in a way that throws off his vertical axis. But it’s not only his body, which was my primary focus, that is distorted: it’s the entire room. (The video is projected floor to ceiling.) Studies interrupts the human condition of our sense of our bodies in space; time – like language, like the body – appears out of joint. The bottom seven channels are moving at a slightly different rate from the top half.

In a work from 1968, First Hologram Series: Making Faces B, Nauman’s face – that element of his body missing from Contrapposto – is contorted in a green, holographic image projected onto glass. The artist has pulled back his lips with his hands to bare his teeth. He appears, in a green glow, to be disembodied. Is this what it means to make a face? But don’t we all know what a face is supposed to look like? Yet, if faces can be made, invented, changed, Nauman seems most interested in the disturbances that ripple through subjectivity. This work made me think of resistance to facial recognition and how, from phrenology to criminology to facial-recognition technologies, the face is always an object of biopolitics and taxonomy.

Nauman is less occupied with ending what Giorgio Agamben calls in The Open: Man and Animal (2002) the ‘anthropological machine’ than he is in laying bare its inner workings and questioning its protocols. On this point, Nauman’s two-channel video of an inverted cowboy on horseback, Green Horses (1988), contrasts with his pyramidal foam sculpture of animal cadavers, Leaping Foxes (2018). Rather than merely comprising a display of interspecies companionship and care on the one hand and abjection and death on the other, taken together these two works move us to consider relationality and creaturely entanglement, animacy and finitude, all as part of the human condition – in an inescapable spectacle of subjection. In the video Wall/Floor Positions (1968), the artist moves hands and feet on the floor and wall in animal-like fashion. We might read Nauman here as refiguring, and perhaps even refusing, normative human behaviour to invite us to reconsider the relationship between movement and animacy, briefly suspending the terms of that ‘anthropological machine’.

Bruce Nauman, 'Disappearing Acts' runs at MoMA PS1 until 25 February 2019.

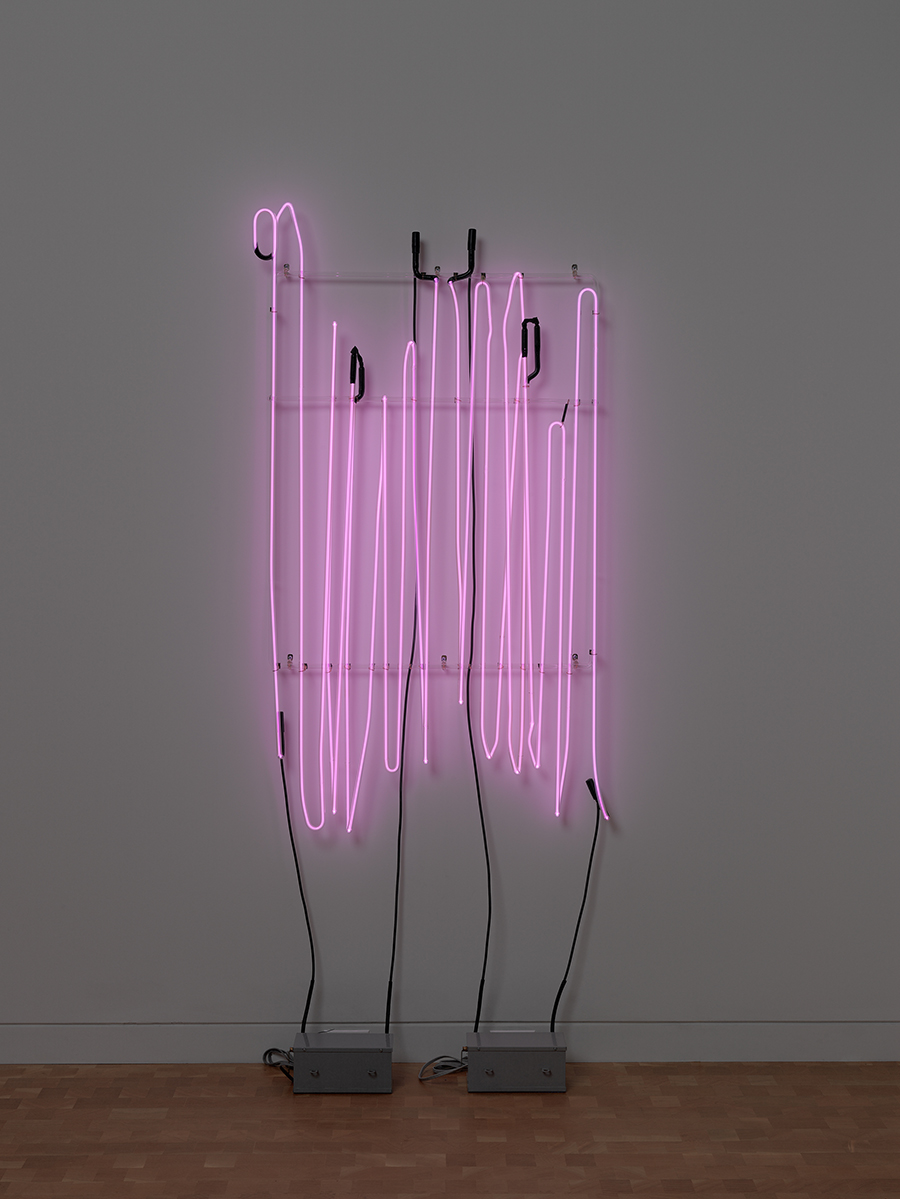

Main image: Bruce Nauman, Human Nature/Life Death/Knows Doesn’t Know, 1983, installation view. Courtesy: © 2018 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; photograph: Ron Amstutz