How to Keep on Clubbing During Lockdown

Through sub-par speakers in bedrooms and living rooms, across cities and continents – queer joy persists

Through sub-par speakers in bedrooms and living rooms, across cities and continents – queer joy persists

Someone is scrunching their hair, smoking and shimmying in a plant-filled bedroom. A person in a sheet mask is bopping their head while nibbling on a chicken wing. Someone else in a tiara, alone in a kitchen, is rolling back their eyes. On Zoom, the dance floor is a grid: a screen stacked with windows of people perusing, performing, chatting, chirpsing, swigging, cereal munching and lipsynching Lizzo’s ‘Truth Hurts’ (2019): ‘I just took a DNA test, turns out I’m 100 percent that bitch.’ Emerging as part of a wider surge in multi-person video chats, Zoom clubbing allows people to hook up virtually and unwind from the stress of social distancing and isolation. With everyone’s cameras switched on and all users pinnable, it encourages an enticing, woozy voyeurism.

We’re at Queer House Party in our living room in southeast London, one week after lockdown was introduced in the UK: a patchwork of neon and fairy-lights, headshots and swaying silhouettes fills the screen. Some London flatmates, donning leather and lamé, hop as the beat builds, fanning themselves like superstars. Two people bop and roll in front of a tropical beach-themed virtual background; a giant cat pixelates over their heads. A Marie Antoinette figure in a moustache grins suggestively to Mousse T’s ‘Horny’ (1998). Hosted by artist Liv Wynter, with resident DJs Harry Gay, Wacha and Passer, the party makes its policies available on the safeguarding page where the link to the meeting is shared. ‘This is a queer-run space. We will not tolerate homophobia, transphobia, whorephobia, misogyny, misandry, racism, sexism or any hate speech against any religion or belief.’ On its first night, the event reached 1,000 people.

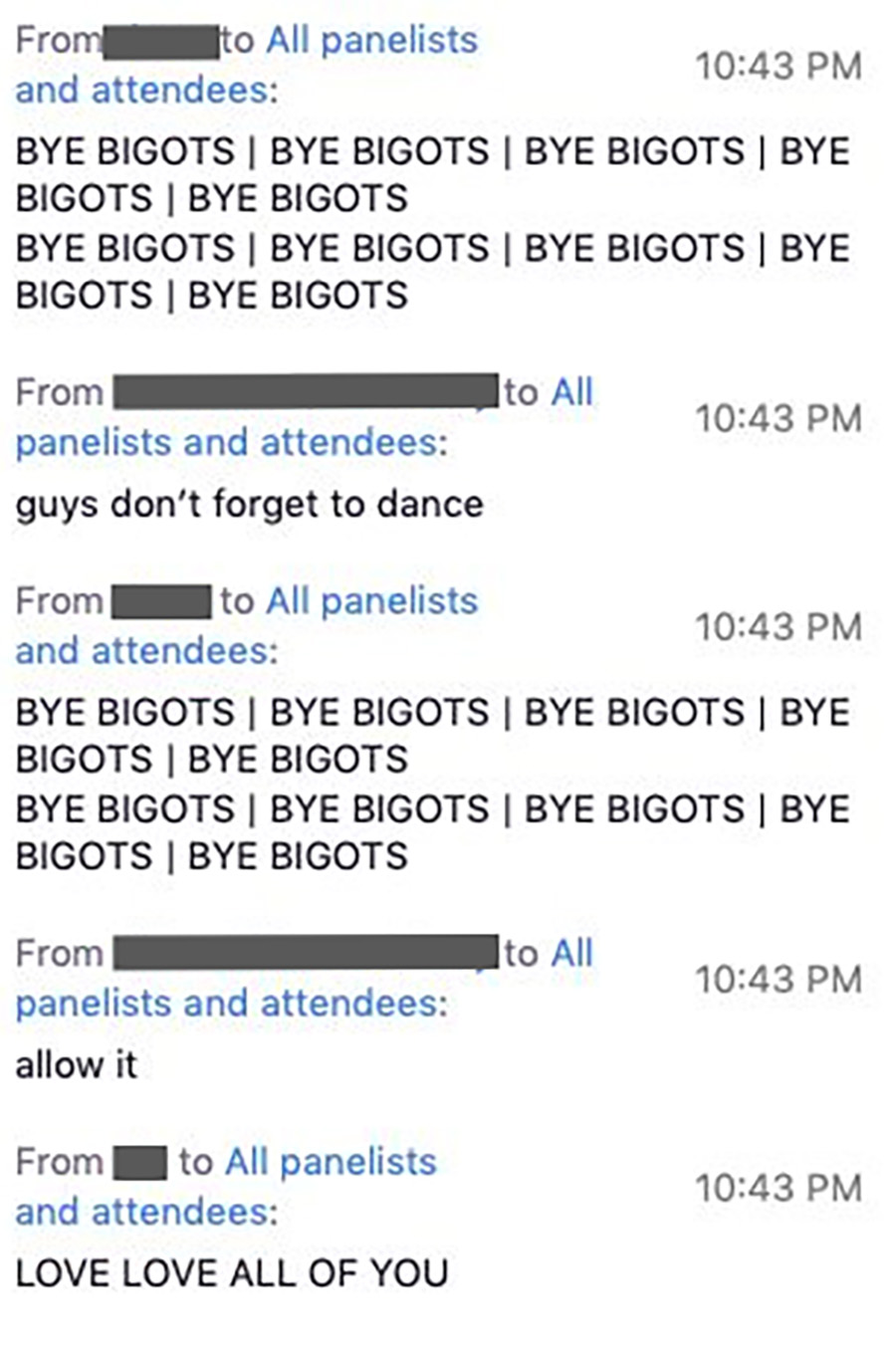

At one point, there’s an outburst on the chat sidebar. Someone is spurting racist abuse in block capitals, like some deranged trollbot. People quickly countertroll and, before long, the user is blocked and the party resumes. As we pin and zoom in on these people, we get caught in a loop between who we’re watching and how we’re appearing. Our eyes dart between them and ourselves, wondering if our gazes will meet. Instead of making ourselves known by direct messaging, we trawl on, eye-fatigued but insatiable.

At Cloud 9, a daytime party is happening. The energy is unreserved and warm. Hosts randomly spotlight guests who, when they realize, start dancing while the chat complements them and people move along. ‘24-hour RAGE TWERK SCREAM TWIRL CELEBRATION THAT WE THRIVE ON DEEPLY INTERTWINED LOVED’, reads Cloud 9’s bio. Cups and bottles clutter kitchen tables as relaxed grooves fill the air, hinting that this party has been going on for a while. Organized by New York-based collective BUFU and China Residencies, the event was developed by a network of QTPOC artists as part of a wider community-support initiative titled CLOUD (Collective Love on Ur Desktop). Their recent programme has included ‘Readings From Mothers: Black Women Writers’, ‘Morning Movement Meditation’ and ‘Sexting at the End of the World’.

The following day, we roll out of bed in time to catch Sunday Club on twitch.tv at 4pm in Berlin. To a soundtrack of house grooves that feel light but keep us going until 10pm, people make cinnamon rolls, join from parks, dance and project their images onto the main screen. This party is smaller than the others we’ve attended: it’s friendly, artsy, DIY. Pitched as ‘an interactive live-streamed participatory art and dance ritual’, the event encourages guests to send videos of themselves dancing in their rooms or to join live via Google hangouts. You can tell people know each other when they choose to unmute their mics to say hi.

The crowd at London- and Brighton-based Gal Pals is buzz cuts, bleach dies, dances with dogs and a Girls Girls Girls sign in pink neon. Centring on womxn, trans and non-binary people, this DJ duo plays only women bangers. Fifteen minutes into the party, we can tell guests are excited to see each other again as they smile into their cameras. At one point, a participant unmutes their mic to spout sexist, transphobic and racist slurs over the music. Everyone is startled and stares into the screen confused. Someone shouts back: ‘Go get off at Pornhub!’ Within seconds, each screen turns black and the party is shut down.

Having addressed the incident on their Instagram story, Gal Pals relaunched the event 15 minutes later by asking attendees to message them for a private link. As people trickled back in, the night kicked off again and soon descended into us singing into our sangria to remixes of Rihanna and Taylor Swift. Gal Pals came back stronger by adapting their security measures and hosting a second party the following week; further events are scheduled for this month.

Targeted harassment is taking new forms with Zoombombers managing to infiltrate virtual meetings of all kinds – from religious groups to school classes – with shocking imagery and hate speech. Queer and trans organizers accustomed to navigating safety in physical spaces are now adapting to a different set of dynamics online.

All the parties we went to explicitly stated their zero-tolerance appproach to harassment and non-consensual activity, often highlighting who they were for, and stating their responses to online safety. This encouraged users to make informed decisions on whether they should join. The parties also gave consideration to how guests were admitted: where Gal Pals now have people individually message them to gain access, Queer House Party uses a public link but hand-picks who can show their video. Another way these places are preserving their integrity is by muting participants and having moderators on hand to respond to any issues that arise, provide tech support and address guests’ concerns.

Virtual clubbing may outlive the lockdown measures and stick around in the long run. As people continue to leave their trails in these online clubs, event hosts should make their chosen platform’s data practices explicit and communicate that what people display might be made public. Organizers cannot wholly ensure participant privacy, and transparency around this subject is crucial.

Virtual clubbing has its perks. With each party creating a completely different dancefloor in our living room, we bopped into the New York, Berlin, London and Brighton queer scenes within the same week. Organizers are building spaces of mutual recognition, where people with shared identities connect, communicate, dance and flirt outside of everyday prejudices and marginalization. In the context of COVID-19, these parties offer a refuge to queer and trans people.

The global accessibility of these spaces has a flipside. Considering that more than 70 countries still criminalize homosexuality, not to mention the oppressive data practices common to online platforms and a history of trolling against LGBTQ+ people, queer organizers can be caught in a double bind. Yet, to disparage virtual clubbing as a hotbed of abuse is to undermine the resilience of the communities behind it. Descending from a legacy of fearlessness in the face of hate, organizers are agile at sidestepping the potential dangers and, rather than dismiss them altogether, are utilizing the resources available to them by adapting technology to meet their needs. The politicization of queer and trans lives renders these parties acts of resistance.

The nights we attended included hits from Bonnie Tyler to Gloria Gaynor – the kind of karaoke ballads that feel somehow appropriate for a sudden release of pent-up emotion – but how they’ll develop remains to be seen. Queer House Party ends every set with ‘What’s Up?’ (1992) by 4 Non Blondes. ‘What’s going on?’ No one knows. But, consciously or not, queer and trans organizers are sending a message to their community: ‘Hey, this is wild, but we’ll pull through it together.’ Amidst the general disorientation – through sub-par laptop speakers in bedrooms and living rooms, across cities and continents – queer joy persists. As one Queer House Party guest reminded the crowd amidst the trolling spam in the chatbox: ‘Don’t forget to keep dancing!’

Donations:

Queer House Party

Cloud 9

Sunday Club

Gal Pals