‘I Believe Deeply that the Best Kind of Art is Public’: An Interview with Senga Nengudi

The legendary sculptor and performance artist talks liquid sculpture, the politics of dance and the liberating qualities of nylon hosiery

The legendary sculptor and performance artist talks liquid sculpture, the politics of dance and the liberating qualities of nylon hosiery

As a member of a radical generation of Los Angeles-based artists who emerged during the turbulent Civil Rights Era (1954–68), Senga Nengudi’s practice has expanded the threshold between sculpture and performance art. At a time when traditional media had given way to the dematerialization of the art object, Nengudi set about inventing her own artistic language with little more than a pair of nylon stockings. In her early experiments, skin-like materials filled rooms and spaces, having been stretched and pulled, tied and knotted, twisted and suspended from walls and ceilings. Compelled by the kinaesthesia of the body, she began experimenting with various forms of movement and collaborating with fellow artists, such as David Hammons and Maren Hassinger. In these performances, the artist’s anthropomorphic forms became extensions of live bodies, transforming sculptural materials and found objects into ritualistic environments of political and civic activation. In her best-known series, ‘R.S.V.P.’ (1977/2003), the splayed, limb-like, nylon forms speak not only to the question of women’s delimited roles in contemporary culture, but also to the physical reality of the artist’s changing pregnant body. Drawing on references as seemingly varied and unorthodox as Japan’s Gutai Art Association and traditional West-African masquerade, Nengudi’s expansive practice allows the material, as well as the viewer, to embody another dimension. In social spaces where blackness is so often circumscribed through mental constructs, Nengudi’s works continue to generate spaces of memory and meditation, spaces in which to reflect on the aesthetics of African diaspora and its futures.

Osei Bonsu You began practising as an artist in Los Angeles during an era of cultural nationalism and civil unrest. For many of the artists who migrated west, the city seemed to be a place of utopia and possibility, extending a longer narrative of black migration. What did it mean to be an artist in LA during this period?

Senga Nengudi I moved to Pasadena from Chicago as a child, so it wasn’t as if I had some romantic notion about moving to LA. Growing up, I never looked at LA as the place to be. In fact, there was very much the notion that everything was centred around New York, artistically speaking. We, as artists, were doing what we did under the shadow of New York and this sense of inferiority extended to the music scene as well. Things have changed since but, at the time, we were fighting to be seen. But we did our work and stayed focused on our vision.

OB While a student in the 1960s and ’70s, you began teaching in the dance and art departments at the Pasadena Art Museum and the Watts Towers Arts Center. What role did your experiences there play in your practice?

SN It all seemed to intertwine like a tapestry or a weaving. I had my own sensibilities, of course, but being in those environments allowed me to explore alternative directions. They also allowed me to focus and intensify my interests in a particular way because of what I was exposed to. Watts Towers Arts Center really pivoted around Simon Rodia’s way of thinking, his spirit of going around and collecting found materials and then incorporating them into his cement towers. After the Watts Rebellion in 1965, the tower was one of the ways we were able to look at life and art differently. Up until then, many artists were academically trained and used traditional materials. This concept of art is blown away when the place you live in is being burned to the ground. You have to think of another way. It makes perfect sense that you take what is left and form it into something that gives you strength and personal power, like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

OB How did you relate to other members of the Los Angeles art community at the time?

SN Things started shifting. There were some of us, like myself and David Hammons, who began to think about things differently. I had barely met Maren Hassinger at the time. There was the well-established Brockman Gallery, run and owned by Alonzo Davis, and Gallery 32, run by Suzanne Jackson, the city’s first black female gallery owner. Her gallery had a relatively short life but a major impact on our community, especially for women of colour. Then there was Pearl C. Woods Gallery, located above a church building and run by Greg Pitts, an artist and art historian. Greg’s place was a home for those of us going out on a limb. At the time, some of us were really enamoured with Sun Ra, Art Ensemble of Chicago and Cecil Taylor. Our ideas were becoming more performative and, from the mid-1970s onwards, we were interested in radical or unusual forms of collaboration.

OB Throughout your career, you have explored the space between dance and the body in movement. When did you begin to cultivate an interest in dance as a practice?

SN I was formally trained insofar as I took classes but I was never really involved with a major dance company. Ever since I was a child, I couldn’t really separate which I liked most between art and dance. I really loved dance but I didn’t like the politics of the dance world; I found it restricting – especially in terms of my body, race and appearance, and how dancers were expected to look at the time. As someone who has always danced to the beat of their own drum, so to speak, it was very freeing to be able to move in a way that wasn’t typical or restricted to someone else’s choreography. I was interested in dancers who struck out on their own, like Eiko Otake and Takashi Koma Otake with their butoh-style choreography, and I was also impressed by Pina Bausch. This way, I was able to incorporate dance into my other visual interests. Today, I am almost obsessed with looking at people and observing the vocabulary of their movements. Just as each person has their own style of handwriting, so they have a particular body language that they’re often not aware of.

OB Some of your earliest ‘Water Compositions’ from the late 1960s involved filling plastic bags with water. This condition of permanent transition seems to have guided much of your work.

SN Personally, I like materials that are transformative, when there is another use for them. I am particularly interested in this notion of shape-shifting. Water became this amazing material for me: it can be frozen solid or liquid; it seeks its own level. Water, more than any other natural element, has so many different forms. It is so powerful, so healing, so nurturing; but, it can also drown you. When I began to put water into vinyl plastic forms, I was exploring that. The ‘Water Compositions’ had to do with the body in the sense that they yielded to your touch. They produced a sensual experience. I stopped making water sculptures when water beds became a commercial fad.

OB This idea of tactility was central to your early practice, so it seems rather ironic that your work is increasingly shown in museums where such interaction is usually forbidden.

SN For me, it’s very hard because I believe deeply that the best kind of art is public art. Art is for everyone and should always be accessible. I believe that public art plays a tremendous role in influencing people. In a museum environment, art isn’t always there for you. Most exhibits have a limited run. One of my thrills is to go to the Museum of Modern Art and look at Claude Monet’s Water Lilies (1914–26), to just be with that piece and see its surface before my eyes! You don’t always have that luxury. My own artwork is so delicate that it’s often not even an option.

OB Your work is ephemeral due to its form as well as its materiality. You started working in this way at a time when sculpture was bound to a masculine tradition of permanence. Were you specifically addressing this?

SN It was a sensitive subject. Because of the materials and compositions, I often found that women were more receptive to my work than men. I’ve often gotten responses from women about how they connect with it, in terms of expressing their internal selves and the tensions of being a woman in the workplace. Or simply of being a woman. One day, some men who were working at a gallery came in and started looking at my work. Initially, they were laughing but, as they observed it more carefully, they became almost sombre.

OB I’m especially interested in the radical performance works you organized in collaboration with Maren Hassinger. How did these come about?

SN Brockman Gallery was the established agent to run and administer the federally funded Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) programme in the 1970s, which was fashioned like the Works Progress Administration (WPA) programme of the 1940s, and hired artists to complete public artworks. Maren and myself were two of maybe ten artists in that programme, and that’s when we became friends and realized our common interests in relation to dance and sculpture. We became part of Studio Z – a loose collective of artists – and would run around town staging art actions wherever there was a location that called to us. Sometimes, we were just responding to the moment.

OB When did you realize the work’s spatial possibility?

SN I think the lightbulb moment came when I decided upon the pantyhose. I had been looking for a material that would give a sense of the body and have the same characteristics of elasticity and flexibility. I played around with so many different materials: I tried using resin to make sculptures hold but they lost that bodily quality. Every time I tried to make the work more permanent in some way, the sculptures just lost their energy. Once I began really playing and exploring with nylons, the process automatically brought about a sense of performance. I am very shy, so some of my works were private performances, which I would have someone photograph. I didn’t have an audience because the idea was terrifying to me. When Maren was willing to work with me, it was very helpful because that expanded performance possibilities.

OB Who were your influences at the time?

SN My influences were the artists I was surrounded by. David Hammons is brilliant, but also some artists who are less well-known, like Franklin Parker and Joe Ray. In the art history books I grew up reading, there was no mention of black artists. That’s why Romare Bearden wrote his A History of African-American Artists: from 1792 to the Present (1988): to make visible the African-American contribution to visual culture.

OB In 1978, you organized Ceremony for Freeway Fets, a full-length collaboration with Hassinger, Hammons and a small orchestra of musicians. How did this multi-layered performance develop?

SN I wanted it to be a culmination of what I was interested in at the time, which was performance, dance, ceremony and ritual. It was quite euphoric to harness this collaborative energy. The musicians were actually visual artists who knew how to play instruments and everyone there was part of Studio Z. I thought of the performance as a christening of the public artwork that I had installed under the freeway. Somehow, through ceremony, I wanted the work to be properly ‘blessed’. I dealt with my shyness by performing under a tarp and mask, which felt transcendent. It was an extension of being influenced by and interested in African traditions. An observer remarked how the performance seemed both African and Japanese in its aesthetics, without knowing how much I love both cultures.

OB Could you talk more about your interest in these cultural traditions?

SN Just like every black child, I was made to go to church and I have always been interested in the spirit, but not in relation to religion per se. There is a spiritual belief system in almost every culture and that has always been attractive to me. I remember going to the library in junior high and looking up Greek gods only to realize how connected they were to Yoruba deities. Whether it’s an Indian roadside altar or a magnificent Brazilian cathedral, I am fascinated by how something becomes charged with a spirit.

OB In the late 1960s, you spent time in Japan and began to study the activities of the Gutai Art Association. What did you find appealing about Japanese art?

SN I applied to study in Japan because I thought it would offer a totally different point of view, and I was right. I chanced upon the work of the Gutai group at the back of a book on contemporary Japanese art. I immediately knew Japan was the place for me. Although I arrived there in the late 1960s, I never came across them or their work.

I loved the simple and purposeful way in which things were done – from traditional tea ceremonies to ceramics that are intentionally made to look imperfect. I was also excited by the sense of movement you see in traditional Japanese Noh theatre and the layering of emotional experiences I encountered in Kabuki.

OB That sense of refinement and utility seems to be central to series like ‘R.S.V.P.’, which you have recently revisited in your newer series ‘RSVP Reveries’ (2007–ongoing). Like human bodies, these works are constantly evolving.

SN When I first started the ‘R.S.V.P.’ series, I used a lot of found materials. When I decided to begin re-creating the works, there were certain pieces I could not duplicate because of that. So, I started to think about the newer pieces as ‘reveries’, dream-like reflections on the original works. With these works, I discovered a new means of expression through materials that was compelling and revealing. ‘R.S.V.P.’ has a lot to do with the tension between material elements and the body and, even though I’m more mellow now than I was when I began making them, that tension is still there.

OB Finally, I wanted to ask you about the physical mobility of these sculptures as they’ve taken on lives of their own. How do you reconcile the detachment of the sculptures from your own labour?

SN That is a difficult question. I am thinking more about the early days when no one had any money and the alternative galleries we worked with had no budget. Danny Davis, a friend of mine who was a musician with the Sun Ra Arkestra, had just come back from a tour in Egypt. He had a huge leather travel bag from which he pulled out a number of magical objects. This experience hit a chord and got me thinking: we women conventionally carry our lives around in our handbags! I soon figured out that I could put a whole exhibition in my bag, pull it out and stretch the pieces out enough to fill a gallery. Now I have works that travel all over the world, but I’ve had to give up personally installing them because I know I’m not going to be here forever. I’ve had to let go.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 198 with the headline ‘Yield to Touch’

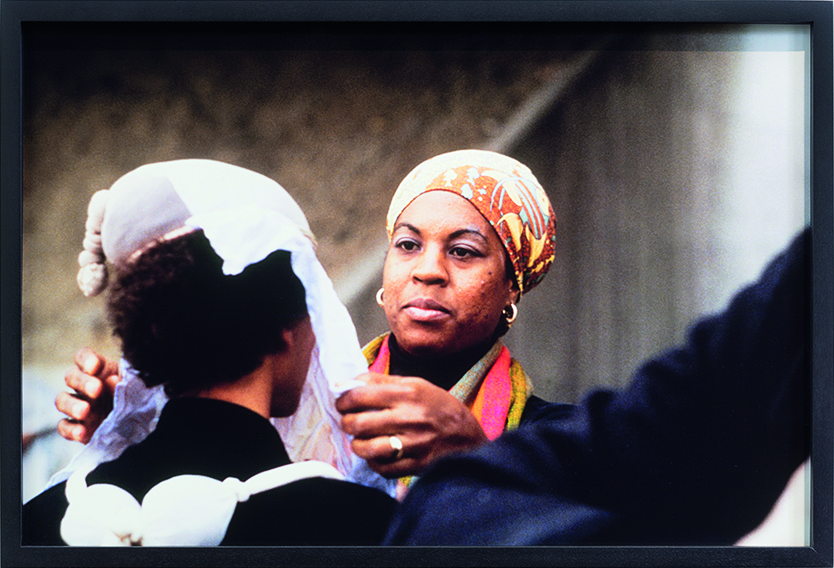

Main image: ‘Head Back and High: Senga Nengudi, Performance Objects (1976–2017)’, 2018, installation view. Courtesy: art + Practice, Los Angeles; photograph: Joshua White