I See, So I See So: Messages from Harry Smith

Temporary Gallery, Cologne, Germany

Temporary Gallery, Cologne, Germany

A ‘medium’ has the capacity to transmit as well as to transform, and it is perhaps with this understanding that filmmaker and ethnomusicologist Harry Smith once said: ‘My movies are made by God; I am just the medium for them.’ Best known for his influential Anthology of American Folk Music (1952), Smith produced 23 films during his lifetime before spending his final years as ‘shaman in residence’ at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. ‘I See, So I See So: Messages from Harry Smith’ takes the prodigious polymath’s life and oeuvre as a springboard to explore the idea of the medium, in technological as well as spiritual terms. Curators Regina Barunke and Anja Dreschke have assembled works from the late 1950s to the present that examine the artistic appropriation of ecstatic practices, their mediation and the metaphorical correspondences between the two.

At the centre of the gallery sit 18 of Smith’s String Figure constructions (c.1970), which provide a glimpse into his vast anthologizing endeavours. A taxonomic collector of colloquial things, like paper planes, Smith submitted everyday stuff to his own cosmological worldview. In his hands, strands of raw cotton twine, looped and twisted into varied configurations and glued onto black paper, seem to create a language of their own. Their sinuous forms assume an unexpected correspondence with the grid of nine spiders’ webs in Rosemarie Trockel’s What It Is Like To Be What You Are Not (1993). Trockel’s silken lattices, each aberrant in its own strange way, reveal the effects of psychotropic drugs on arachnoid behaviour. Borrowed from the results of a 1948 pharmacological experiment, each web might be seen to embody an interface between the spider’s physical world and various altered states of consciousness. On the opposing wall, spiders and sensorial experiences resurface in Franco Pinna’s photographic series ‘Il tarantismo’ (Tarantism, 1959), which documents an anthropological study into a popular form of musical exorcism used to remedy the bite of a tarantula in Italy’s agrarian south.

The ethnographic impulse can also be traced in films by Peter Adair and Tamar Guimarães & Kaspar Akhøj, which apply divergent approaches to representing collective spiritual practices. Adair’s Holy Ghost People (1967) is an unassuming, intimate account of a religious movement in the American South. Shot with a handheld 16mm camera, the film traverses a crowd of believers as their movements quicken and their fervour erupts into wild-eyed rapture: bodies convulse, people speak in tongues, preachers wrestle venomous snakes. Meanwhile, Guimarães & Akhøj’s film, A Família do Capitão Gervásio (Captain Gervásio’s Family, 2013–14) turns to a Spiritist community in Palmelo, Brazil, whose resident mediums invoke the spiritual through more meditative means. Crepuscular shots of the town’s healing centre are coupled with images of Brazilian modernist architecture, evoking a network of ‘astral cities’ that Spiritist mediums envision as utopian versions of their own. While Adair’s treatment of the camera as a direct means of capturing reality seems to affirm the ontological objectivity of cinema, Guimarães & Akhøj’s shots occlude as much as they reveal, producing a more speculative space.

Works by Wallace Berman and Apichatpong Weerasethakul explore the extent to which technology can function as a mystical conduit. Compelled by a life-long interest in the Kabbalah, Berman deploys a found image of a hand-held transistor radio to allegorical effect in his Verifax collages (represented here by the 'Radio/Aether' series, 1966/74) and in the slipstream of images that make up his only film, Aleph (1956–66).

Weerasethakul’s Windows (1999) is a digital ‘flicker film’ of sorts, made whilst the filmmaker was toying with the camera eye’s mechanism in his hotel room. Against this intimate backdrop, the silent pulsation of colour and light becomes increasingly stroboscobic, inevitably recalling Tony Conrad’s iconic Flicker (1966). But whereas the source of Conrad’s hallucinatory effects is revealed within the material of his 16mm filmstrip, Weerasethakul’s source remains enigmatic, like seeing the world through a ‘spiritualized’ camera.

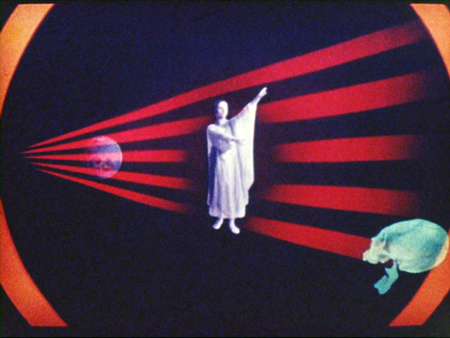

This hypnotizing, disorienting flicker might lead us back to Smith, who strove to achieve a mystical correspondence between the senses through experiments in visualizing music. In films such as Film no. 17 (Mirror Animations Expanded) (1979), a mandala-like collage animation of hermetic imagery set to Thelonius Monk’s signature piano riff, Smith seems to channel an inner kaleidoscope to marry image and sound. While such films now risk appearing naive and marred by new-age clichés, the lure of the cosmic still captures the artistic imagination.