Iconoclash

Oliver Laric uses memes, movable type, copies and collective agency to make art that is only partly ‘his'

Oliver Laric uses memes, movable type, copies and collective agency to make art that is only partly ‘his'

Oliver Laric once showed me a 16th-century print by Flemish court artist Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder. The etching depicts a scene of iconoclasm, or Beeldenstorm, during the Reformation, when churches and public spaces in northern Europe were systematically purged of religious imagery, often by mobs. Hallucinatory in its detail, the print shows a swarm of figures on a mount pillaging icons, breaking statues, tossing altarpieces into a fire. Birds in the air shit on monks beside bare trees that crown a bald outcropping; broken relics and shattered crucifixes jut out like gravestones from a pit.

Gheeraerts’s work isn’t simply a depiction of image breaking. When viewed from afar, the mass of active figures in the print forms a new, anamorphic image: a grotesque, composite illusion of a monk’s rotting head. An assembly of small bodies forms a sagging mouth (full of drunken townsfolk), and a group of monks ploughs a field that’s also the head’s wrinkled brow; a monkey stands inside an ear, and the figure’s nose is formed by a crucifix about to be toppled between two hollowed-out eye sockets.

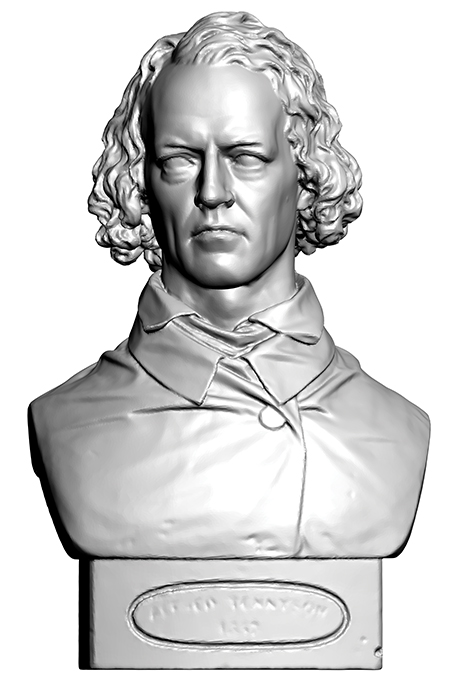

I don’t think Laric had ever seen the real Allegory of Iconoclasm (c. 1560–70) – which exists only as a smallish, unique print in the British Museum – when he introduced me to Gheeraerts’s work during a conversation about his own video Versions (2012), the third in his series of that name, in which the monk’s head appears briefly. I write ‘real’, although Laric’s information-driven videos and sculptures confound distinctions between real and fake, even making that effacement their subject. I write ‘own work’, despite Laric’s ongoing concern with the mutability of authorship and ownership. An author is fungible, particularly as enabled by recent forms of collective and participatory labour. Internet memes, popular and children’s films, super-cut YouTube videos, medieval sculptures, outsourced remakes and the ‘participatory’ labour practices of North Korean monuments are all found, re-remixed and translated in Laric’s works. And although I write ‘conversation’, that word only partially accounts for the hopscotching, hyper-medial surge of links, flickering images and n+7 web results that the artist retrieves, combs through and reassembles to display and comment on his own material, as well as that of others. ‘I sometimes Google terms that seem to have nothing to do with each other,’ Laric says. ‘“Mikhail Bakhtin and prosumer” or “Samuel Beckett and Teletubbies”. Usually, there’s an unexpected link.’ In the latter case, it might be Beckett’s Quad (1981), whose four actors could be proto-Teletubbies; in the former, it’s Bakhtin’s dialogic understanding of how production oscillates between collectives and individuals – a dialectical motor Laric puts to work in his collectively-based pieces.

There is no distinction between the material Laric finds and that which he presents as his own. Laric’s exhibition ‘Kopienkritik’ (Copy Critique) at the Skulpturhalle in Basel in 2011 took its cue from the 19th-century methodological approach to philology and ancient sculpture, which viewed (inferior) Roman ‘copies’ in terms of (superior) Greek ‘originals’, reconstructing those lost originals via the bulk typologizing of inferior later copies. Laric cast and grouped that museum’s collection of Greek and Roman plaster casts into typologies, alongside video monitors and heads cast by the artist. ‘Copyright did not exist in ancient times, when authors frequently copied other authors at length in works of nonfiction.’ This declaration does not come from a history of literary influence, but from the GNU Manifesto, written by MIT’s Richard Stallman in 1985 to announce an influential, free software, mass collaboration coding project (and the theoretical backbone to much open-source digital content today). ‘Be promiscuous,’ reads an Open Source Initiative manifesto encouraging coders to distribute their works free of charge. Laric draws on this ethos of collective reworking.

Although you can find it on YouTube, Laric’s Touch My Body: Green Screen Version (2008) is not really a video but rather a participatory game, or dare, that Laric intended to be appropriated and modified. For Touch My Body..., Laric stripped Mariah Carey’s music video for her 2008 song of the same name of all but Carey herself, and replaced it with a green screen, against which any background could be inserted. When Laric posted the piece to YouTube that year, users took the cue and began uploading amateurish, witty remixes using Laric’s template. (Including one with a background of zombie gore taken from Sean of the Dead, 2004). Today, the first result when searching for Laric’s piece on YouTube is not his original video, but an amateur mash-up, of which there are many.

Memes – like fame, lies and capital – accrue value and cachet as they circulate. But they also date and flatten, and while Touch My Body ... lacks the complexity of Laric’s later pieces, it demonstrates the atmosphere in which his work arose: the newly ‘social’ internet; the advent of the ‘prosumer’ (‘producer-consumer’ or ‘professional-consumer’) technology that enabled easy editing by 15 year olds; online video-sharing platforms; freely accessible, though commercial, image repositories such as Getty Images and Flickr. On a larger scale, the points of departure for Laric’s works have been incipient shifts in group structures and collective agency (shifts not limited to the internet), the global political atmospheres of what in the mid-2000s began to be called ‘truthiness’: a simultaneous reliance on, and distrust of, circulated images and narratives.

The striking succession of historical images that opens the first of Laric’s essayistic video series ‘Versions’ (2009–12) is as much a comment on political shilly-shallying as an assertion of the masses’ new claim on image production and circulation. The video, which is a trove of examples of the fraught status of reproductions and copies from recent and contemporary material culture, begins with an image (released by Iran’s state media to Agence France-Presse in 2008) of four missiles, which was used to illustrate Iran’s missile tests when it appeared on the pages of the Los Angeles Times and the Financial Times, among many others; following this, Laric inserts a graphic that indicates how that image was clearly manipulated, if not fabricated, using Photoshop (the multiple missiles are effectively copy-and-pasted from within the image). And finally, a series of user-generated spin-offs of the Photoshopped image showing dozens of missiles, their streams in comic curlicues. I can’t think of any better way of exemplifying Jean Baudrillard’s ideas about simulacra and hyperreality in our age of truthiness than this simple slideshow compiled by Laric.

Until a few years ago, the internet was the main (and often only) way to see Laric’s works, and those of sanctioned fellow artists. Before I ever heard of him, I would often look at VVORK.com, the influential blog he ran from 2006 to 2012 with Aleksandra Domanović, Christoph Priglinger and Georg Schnitzer. The set-up was simple: an art work or two posted daily, either by one of the four founders or (usually) by another artist. VVORK would ‘curate’ not only images of contemporary works but also historical ones, predating that now-orthodox usage of Tumblr, and still contrasting with exhibition-based blogs like Contemporary Art Daily. On a random day in 2009, these posts might include a 2001 tray installation by Brian Jungen, a 2009 work by Markus Schinwald, a 1967 piece by Les Levine, and the ‘Silhouettes’ series (Untitled) by Seth Price, whose 2002/2008 essay ‘Dispersion’ continues to be one of Laric’s conceptual cornerstones. Laric believes – like Price, and as Marcel Broodthaers is quoted as saying at the beginning of the ‘Dispersion’ essay – that ‘artistic activity occurs, first of all, in the field of distribution’.

Laric, whose first solo show in Berlin was in 2012, says that ‘for many artists, distributing images of their works online happens secondary to physical exhibition. For me, the online distribution happened first.’ Distribution is the aim and theme of his recent Lincoln 3D Scans (2013) – the result of his receipt of the Contemporary Art Society Annual Award – for which he is 3D scanning and publishing 3D models of the complete holdings of the Usher Gallery and The Collection in Lincoln, to be used in an unknown fashion, for free, and for any reason – whether advertising, garden decoration, scholarly research or design. Despite the expense and technological expertise required for such a task, Laric is driven by a bootleg, Samizdat-like stance, shared by other artists working with the internet as medium, one with art-historical roots in conceptual art’s blurring of documentation and event, work and distribution, as well as in the history of design.

More particular to Laric’s work is how this axiomatic stress on self-dispersion is also an attempt by the artist to self-efface, to swamp the ego in an ocean of collectivity. Viewed from a distance, this attempt is the allegorical gist of Laric’s entire project. Above all, it’s the ambiguities of invisible labour that Laric explores. This concern is also perceptible in his discrete objects: the 3d printed sculptures of Reformation-damaged Icons (Utrecht, Worcester, 2009), or the 2013 ‘everyman’ statuette Laric commissioned from the North Korean Mansudae Overseas Projects, a factory in Pyongyang specializing, controversially and rather terrifyingly, in creating communist ‘realist’ kitsch monuments.

The paradoxes of collective authorship also draw Laric toward religious objects, as well as memes, whose communal authors are anonymous: both are acheiropoieta, or ‘made without hands’, as Laric points out, using the theological term for icons which are said to have originated without human intervention. ‘Long before the hammer strikes them, religious images are already self-defacing,’ wrote art historian Joseph Koerner, who also provided Laric with the words for the sweeping iconoclastic scene with which the 2010 Versions film begins. In the middle of that video, the narrator announces how ‘for the first time several months ago, I spent hours looking at the façade of the cathedral. But only when I bought a book on the cathedral a week later did I really see it. The photographs enabled me to see in a way that my naked eye could not.’ Laric’s point here – or the narrator’s, or Susan Sontag’s, who said these words, or the interviewer’s, who transcribed the text in a book from which Laric appropriated it – is that experience is always already in a state of double-exposure; all production is a reproduction. And, contrary to Walter Benjamin’s ideas, the aura of certain works is not shattered by mechanical reproducibility, but may be paradoxically augmented by it. As suggested by art historian Anthony Hughes, also quoted in Versions, ‘multiplication of an icon, far from diluting its cultic power, rather increases its fame’.

These assertions might come off as didactic without the weight of the three video works’ remarkable examples, culled from material culture, and read over a seamless stream of gnomic, unattributed apercus. Donald Richie’s The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1998), Jorge Luis Borges’s ‘The Homeric Versions’ (1932), Vitruvius, Michel Foucault, studies of mimesis in classical antiquity, all outlining the artist’s ‘innate preference for the represented subject over the real one’, a phrase Laric borrowed from Henry James’s 1892 short story ‘The Real Thing’.

Everything in Laric’s works seems to be saying the same thing – or, to quote Versions, ‘same, same, but different’. That’s precisely Laric’s point, which is that all matter, and all that matters, is repetition. We may have never seen Where The Truth Lies (2005), but we may unconsciously recognize Pierre König’s Stahl House, the Los Angeles modernist villa featured in the film, because it previously appeared in Nurse Betty (2000) and Why Do Fools Fall in Love (1998). Interestingly, the villa was built in 1960 as part of the Case Study Houses programme, before Laric made it his own case study, presenting the three, near-identical portrayals of the villa across three screens in Versions. An odd quote from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Twilight of the Idols (1888) is read over scans of book-printed photographs by Candida Höfer of various cast versions of August Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais (first completed in 1889). The video ends with a 3d-rendered model of a sculpture by Laith al-Amiri installed in the grounds of an orphanage in Tikrit, Iraq – a replica of the shoe that was thrown by an Iraqi broadcast journalist at George W. Bush during his 14 December 2008 visit to the country. Over one poignant, partly silent minute, we see Mowgli from Disney’s The Jungle Book (1967) in split-screen next to Christopher Robin from Disney’s Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day (1968), doing precisely the same things: throwing a rock, walking, interacting with animals. Clearly, and rather unnervingly, they were drawn using the same types, just as in real life the same actor, Bruce Reitherman, provided the voices of Mowgli and Christopher. Moveable type, it seems, is not only the backbone of words and letters, but in an extended sense, the atomized unit of material culture.

Although Laric’s videos claim to advocate the emancipatory potential of such copies, doubles and remakes, they seem to be at their best when their effects are unsettling or contradictory. Art works that affect us keep up the illusion of uniqueness, and draw upon the strength of repetition even as they play down their sources, their status as copies. The ‘Versions’ films are poignant specifically because they play up that loss, that iconoclastic betrayal. Viewing these examples provokes the same kind of uncanny feeling you might have when the illusion of a real bond is shattered: finding out that the alluring scent of a lover was actually a perfume purchased and worn by thousands of others – or, worse, that the bond was the result of that very product. And it’s that betrayal of ordinariness, of non-uniqueness, that Laric brings to the fore.

In the 1920s, the folklorist Vladimir Propp began analyzing Russian folk tales and found consistent, systematic, irreducible types: the hero, the witch, the donor who provides the hero with a magical object, the false hero who takes credit for the hero’s deeds and tries to take the prize. Propp’s unfashionably rigid formalist enterprise later fell by the wayside to the more expansive locutions of post-structuralism, after scholars like Claude Lévi-Strauss became suspicious of formalism’s strict totalizing impulse. Classification has a tendency to normalize discourse, and all norms are bad, right? But the toppling of ‘totalizing’ theories such as Propp’s – at least until new totalizing theories took their place – was ironic in its timing since it was during the same 1968-era which crowned ‘rhizomatic’ High Theory that popular works of mass distribution, such as Walt Disney’s cartoons, drew profitably and compellingly upon those same types and icons identified by figures like Propp: the good witch, the hero, Christopher Robin, Mowgli. The importance of such icons was, in a way, destroyed by the steamroller effect of theory. But the discovery of moveable types still holds remarkably well in the realm of popular culture, although that culture has since shifted considerably. Like money, monuments or memes on a screen, these icons are efficient, commercial, clean and rather cold. They are immediately recognizable, even when we don’t recall them – or their authors – by name.

Oliver Laric is an artist based in Berlin, Germany. His work is currently included in ‘Damn braces: Bless relaxes’ at Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK, and ‘Art Post-Internet’ at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, Beijing, China. In June he will have solo shows at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, d.c., USA, and The Collection Museum, Lincoln, UK; and in November at AR/GE Galerie Museum, Bolzano, Italy, and Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin.