If the Earth Were a Hot Dog: A Conversation with Agnes Denes

With a survey exhibition at The Shed, the visionary artist speaks to Emma McCormick-Goodhart about the importance of learning from nature

With a survey exhibition at The Shed, the visionary artist speaks to Emma McCormick-Goodhart about the importance of learning from nature

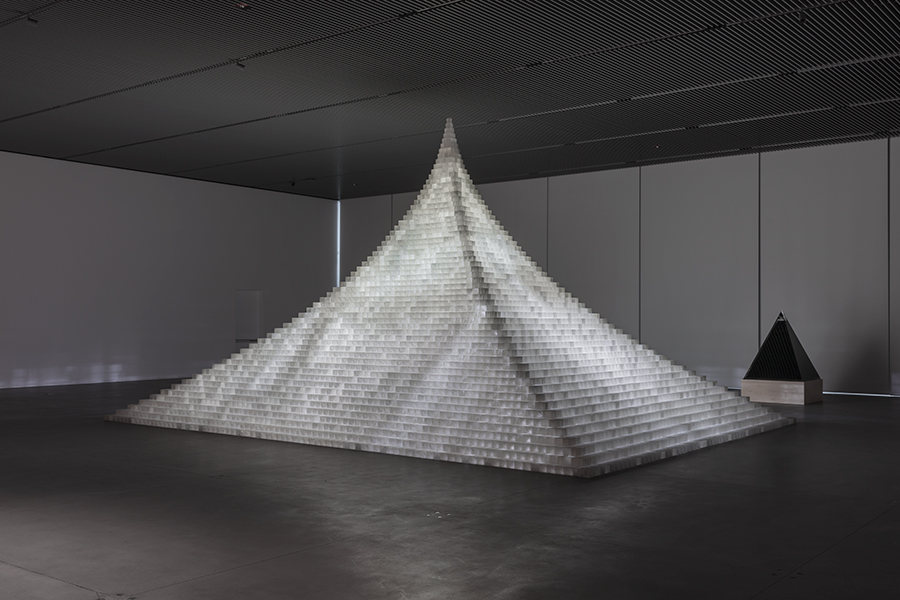

Agnes Denes’s prescient work pushes the limits of the physical world. Many of her structures remain unrealized in the built environment, existing as precise renderings on paper. Her ‘eco-logical’ depictions of cilia, organisms, spheres and hyperspheres stretch from subatomic to planetary scales. ‘Absolutes and Intermediates’, Denes’s solo exhibition on view at The Shed until March 2020, surveys more than six decades of experimentation, from her ‘Philosophical Drawings’ (1969–80) and ‘Map Projections’ (1973–79), to her early experiments in holography and range of public projects. This imaginative cartography engages questions of mind, matter, machine intelligence, ecological precarity and future habitation.

Emma McCormick-Goodhart: Do you recall how and what you played with as a child?

Agnes Denes: I remember having a Robinson Crusoe environment. My father had a small, little estate, and we went there in the summertime, when school was out. I remember dragging a blanket across the field and digging out a little environment under bushes, where it was my space. I remember sitting there and dabbling for the first time in poetry.

EMG: You’ve described how a ‘loss of language’ – a feeling of being ‘deaf and dumb’ – caused by geographic relocations as a child led you to embrace visual vocabularies.

AD: When you travel, you pick up different languages. I picked up different languages that interfered with writing poetry. Somehow my need for creative expression found a way in prose, visual expression, painting, and so on.

When I started, I wanted to evaluate human knowledge. I wanted to re-examine our thinking; and during this investigation, my art was born. At the time, embarking on a project I was attracted to, I didn’t realize that it would take me years to complete. Once you are in something, you can’t walk away from it. That’s how I wound up doing my works that seem like such summations of knowledge in visual form. I feel that difficult concepts can only be understood if they’re put into visual form, and that is the most difficult thing: visualizing invisible processes.

EMG: A body of your work remains unrealized, albeit meticulously rendered. How important is it that a work be ‘realized’, and does it make it any less real if it isn’t? What freedom does not realizing a work, but conceiving of it, confer to you?

AD: It is important for the world to realize these concepts as they offer benign solutions to the problems we are facing. You can take a horse to water but can’t make it drink. The world has yet to wake up and act on intelligent suggestions. My roll is only to propose them.

EMG: What does working without colour, as you did for 15 years, permit in the way of experimentation?

AD: I loved colour, even taught it in school, so giving it up meant divesting myself of something I loved in order to deal with difficult concepts I needed to visualize and put into the foreground.

EMG: You’ve designed environments for outer space, terra firma, coastlines, and the deep sea – some of which are built, and others that exist as concepts or masterplans. Which genre of environment is most interesting and/or challenging to design for? Which feels most urgent to design for?

AD: All of them.

EMG: How has your Mega Dunes and Barrier Islands to Hold Back the Sea: A Project for the Rockaways and the New York Harbor (2013), a collaboration with climate scientists, oceanographers, Rockaway community organizations and others, evolved since its inception? Do you see sculptural possibilities in island creation – of land and wetland formation?

AD: I designed mega-dunes to slow down the destruction of sea surges for the shores of low-lying areas in the New York Harbor and around the world. And even though the Rockaways signed off on the project, it is still waiting for any real support, like my Forest for New York (2014). The world is slow if there is no motivation, expensive advertising, or wealthy, big-name support.

EMG: You were thinking about sentience and nonhuman intelligences well before the topic was embraced by the philosophical community. Your unrealized piece, Giant Sequoia (1972), reads as follows: A proposal for a film that examines the ‘thoughts’ and experiences of a California redwood that has lived over one thousand years and grown to 300 feet with a trunk diameter of thirty-some feet.

AD: An entity that lives on earth; a tree that’s a thousand years old. What has it seen and experienced in history that lived around it: the demise of people, the growth and the rebirth of people in cities … If that could talk, wouldn’t that be fascinating? I’m just putting myself in the mind of a thousand-year-old sequoia. It’s very simple.

EMG: You also ‘worked with’ plants. Your microphotographic series, ‘Anima/Persona—The Seed’ (1978–80), is both visually opulent and hyper-kinematic, like early stop-motion photography.

AD: I’m interested in growth, in pinpointing growth – not time-lapse photography, necessarily. I’m fascinated by how people change. I used microphotography to photograph a seed, because I wanted to see changes the eye can’t see.

EMG: Many of your works activate the morphology of the shell (Snail Pyramid—Study for Self-Contained, Self-Supporting City Dwelling—A Future Habitat, 1988; Snail People —The Vortex, 1989; the Nautilus Amphitheater in Peace Park U.S.A.—Proposal for Twelve-Acre Park, Hains Point, Washington D.C., 1989, etc.). What fascinates you about molluscs and their capacity for enclosure?

AD: When I was on vacation in Long Island, I started studying hermit crabs. They’re fascinating creatures, because they move out of a house, and they start looking for another house immediately. They’re like real-estate people, little Trumps. They go and find a house and they back into it [she motions with her shoulders] to see if it fits. I try to understand nature, independent of the words man has given it.

I don’t think of this as morphology, which is a man-given thing. I look at it as a parallel to the way we play with the only home we have as humans, this silly little earth. For instance, what would people look like if they were living on an earth shaped like a hot dog? They would be tall and skinny like toothpicks. My drawing that imagines that, Isometric Systems in Isotropic Space–Map Projections: The Hot Dog (1976), is a comic piece, with very serious implications.

EMG: What do you envision as future spaces of practice and exhibition for artists of the future, who have yet to be born? Should we not be practicing indoors?

AD: It depends on what they want to do. I see a lot of art today that, to me, is meaningless. Artists try a little bit of environmental art, a little bit of this, a little bit of that. I don’t see anything beyond the struggle to be seen and heard. It’s good to have so many artists; I wish we had more. But most artists don’t spend enough time on their art.

If your art is well thought-out, it demands its own presentation, it demands its own space. Art has to be strong enough to make room for itself. It has to be strong enough to withstand the public’s lack of understanding.

‘Agnes Denes: Asolutes and Intermediates’ continues at The Shed through 22 March 2020.