How James Barnor’s Iconic Images Shaped the Imagination of a Generation of Black Britons

As a major retrospective opens at Serpentine Galleries, the photographer speaks to Afua Hirsch about capturing the energy of Ghanaian independence in Accra and the swinging sixties in London

As a major retrospective opens at Serpentine Galleries, the photographer speaks to Afua Hirsch about capturing the energy of Ghanaian independence in Accra and the swinging sixties in London

The era of African independence, in the 1950s and ’60s, is more than a moment in history. It is a memory that has shaped the identity of generations. For those of us who grew up decades later, in diasporic media landscapes that groomed us with Afro-pessimism, our only bulwark was to return to that era – one we neither witnessed nor remembered. A time when Ghana and its pan-African neighbours had the audacity to imagine their future as one of freedom, affluence and unapologetic Black pride.

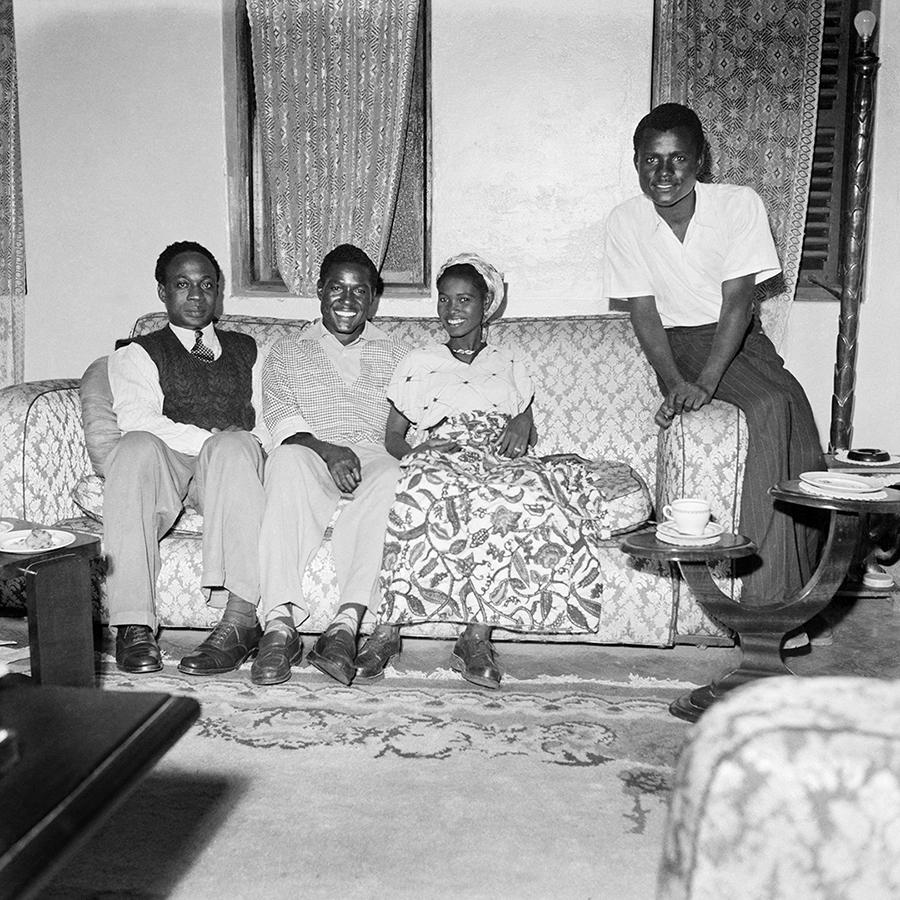

Whenever I visualize this period, it is James Barnor’s images that I see. Born in 1929, and now widely recognized as one of the African continent’s most pioneering photographers, Barnor captured ordinary Ghanaians, from all ends of the social spectrum, at his Ever Young studio in Accra during the 1950s. As a press photographer for the Daily Graphic newspaper, his reportage of the events leading up to and then celebrating Ghana’s independence in 1957 have come to define a moment of extraordinary optimism in my imagination. From his casual portraits of the nation’s first president, Kwame Nkrumah, to the hope embodied in the details of city life, Barnor’s images capture the profound change of the mid-20th century.

The Black, beehive-styled Londoners, clad in mod fashion, who Barnor photographed for Drum – the South African anti-apartheid and Black culture magazine – while living in the UK in the 1960s, are emblematic of the cosmopolitanism that permeates his work: capturing the world in Ghana and Ghanaians in the world.

As Barnor told me in this interview, he only received global recognition more than half a century after his work began, when he was in his 80s. Now aged 91, he has as much energy for photography, storytelling and archiving as ever.

James Barnor I learnt photography from one of the best portrait photographers in Accra: my cousin Mr J.P.D. Dodoo. He was already doing photography when I was a little boy at school. When I went to his studio on the first day, he gave me a book. It was called General Photography, or something. It was full of diagrams and chemical formulas: for reducing a negative, increasing a negative, for developing film, for printing.

I had my tuition from two photographers, and both of them happened to be my cousins. Mr Dodoo had his own studio; Mr Aikins was working for the Information Services. Those were the Gold Coast days, under the colonial administration. Mr Aikins virtually taught himself photography. He got a different approach to photography through books, which he ordered from Fleet Street in London, where the newspapers were based. It was the approach and perspective that I learned from him which made my work more journalistic.

Our trouble, in Ghana, was basic education. I wish I could write like you, but I never got the education that would have made me fall in love with reading and writing. Either because I didn’t get the push, or because somebody helped me part of the way and then couldn’t do any more. So, I had to go and learn photography.

It took me a long time to understand the art in photography. There is a big difference between doing art and doing photography. I have come to realize that, when you get an education, as soon as you see a picture, you already know this should be here, that should be there. You form the story before you take the pictures: you take two or three, and you are on the way.

I only wish I had known the value of negatives, so I could have kept them in better order. When I was an apprentice photographer, copyright laws were different. In those days, when you took a picture, it belonged to the person who commissioned the picture and paid for it; as the photographer, you could not use it – even to display it in your shop, to advertise it – without the owner’s permission. Slowly, artists have fought to gain recognition for producing the artwork.

Do you know the legendary Ghanaian musician Agya Koo Nimo? He keeps asking me: ‘Have you got a picture of Mr Strong?’ I’ve got them, but they are all scattered about. Mr Strong was a mystic who established the first ashram in Accra and had a group of followers. I remember Mr Strong coming to Ever Young with a guitar and playing. I also have pictures of Mr Dodoo’s son, Peter, doing yoga exercises.

Afua Hirsch People often talk about your work at the time of independence – that you captured the energy of the new country, the new era. At the time, did you feel conscious of the profound change that Ghana was going through?

JB I felt lucky that I was part of it. I still feel that way. I was lucky that, with my minimal technical knowledge, I was able to record something. Not everybody could do it. I had gone through a type of training with Mr Aikins but journalistic photography is a very different thing to portrait photography: you are running all the time, you are talking to people, you’ve got to be able to move. I was the first photographer to be employed by the Daily Graphic. It’s something that I hold in high esteem, that I got that chance. The [London-based] Daily Mirror newspaper decided to open a press in Ghana in 1950. At that time, there was already talk of independence – the soup was cooking – and people wanted news. Cecil King [chairman of the Mirror Group] came with his team. They were looking for a photographer. He went to my cousin, Mr Dodoo, who told them: ‘Oh I don’t do that type of work, but I know somebody who does.’

I wasn’t prepared. I got a small box of photographs and showed it to him. He looked at the pictures and said: ‘Not quite, but we will train you.’ We worked for about one and a half to two months before the first paper came out.

AH So you got the practice and experience.

JB Yes. Then, in 1957, with independence, the whole overseas press descended on Ghana to photograph what was going on. That was the first time I saw different types of cameras. At that time, we had the tripods and the big press cameras. But the international press photographers were carrying small things, like a matchbox in comparison. We hadn’t seen anything like that. That is something which makes you want to go to England – to learn to use cameras like that. Before coming back again. That’s why the idea of going to England came to me: seeing the world press in Ghana.

In the summer of 1958, an organization called the World University Service of Canada brought students from all over the world to study the effects of independence on a new African country. They settled at Legon, just outside of Accra. I got to know them. We exchanged a lot of ideas. I thought about travelling to Canada. But, shortly after that, my own schoolteacher, mentor and role model, Alfred Q.A. Archampong, decided to go to England to learn architecture. I said to him: if you go and the place is good, write to me. That’s how I came.

AH How do you look back on your first years in England? What was it like for you?

JB Oh, that’s another thing all together. Coming to a place and meeting people from various countries, not just one. A lot of white people. A lot of Black people. Everywhere. And transportation. And colour. And advertising. And the uniforms that cinema ushers wore. And the red buses and all this. Those were my first impressions.

AH When I look at your pictures of Black people in London in the 1960s and ’70s, they feel so different from other images I’ve seen of the era. Do you think that coming from Ghana, being part of the African diaspora, you had a different gaze to that of the white British photographers who were taking pictures of Black people?

JB Part of it is that those were the people I was around; they were what I had to work with. As a photographer, you take the first available subjects. At the time, in 1959, I don’t think any studio photographer would have employed a Black man to take photographs of his clients.

Fancy how I was with my clients in Ever Young. Either I was touching them or saying: ‘Turn your head this way,’ or, ‘Do it this way.’ I don’t think a white sitter would allow a Black person to do that. No photographer would put you in the studio to work. If at all, it would be in the back, in the darkroom, away from the client.

A lot of my work at that time was published by Drum magazine. If it wasn’t for Drum, I don’t think I would have got the chance to photograph any model that would end up on a cover. When I first came to England, I was living in Kent and studying at Medway College of Art. I remember travelling from Kent to London one time and seeing Drum, with my picture on the cover, on the stalls. I said to myself: ‘Yes, at least I’ve done it.’ You know, in America, Black photographers were taking pictures of Black people for magazines. But, in England, it wasn’t like that. There were no Black photographers at all. I was in England for ten years, until 1969. Then I went back to Ghana to teach.

AH You have said that you found fame aged 79. Is that true? Is that how it felt?

JB Oh yes, I would say so. When I was 79, 80, my pictures started popping up and people started seeing them.

AH Why do you think there was this renewed interest in your work, so many years after you started?

JB I was lucky, in many cases. I had shown some work in an exhibition at Acton Arts Forum, in west London, near where I now live, in the early 2000s. After the show, the organizers gave me the 25 prints, so I had a basis for my own exhibition. They weren’t photographic colour prints, which could be sold; they were printed by graphic designers. But the quality was good.

I always use my birthday as an excuse to show some pictures. I live in sheltered accommodation for elderly people and, for my 80th birthday, I told the warden: ‘I’m going to make an exhibition.’

I filled the town hall in Acton with my pictures and Isaac Osei, who was the Ghana High Commissioner in London at the time, came. I never had much to do with the High Commission, I did my own thing, but there was a receptionist there who was my friend. I mentioned this exhibition to him, and he said: ‘I’ll tell the High Commissioner and he will come; he’s interested in older people.’ So, I waited and he called me and he came. That was the beginning.

My gallery in Paris [Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière] is currently finishing digitizing all of my photographs and putting them in a database. More than 7,000 pictures. I wish that it were all happening in Accra, but there is still a lot that has to happen overseas, because they have the expertise, they have the interest; they put in the capital to do everything. Although I have promised to return them to the Nubuke Foundation, in Legon.

AH When you look back at the photographs from your earlier career, what do you see, now, that’s different from what you saw at the time?

JB I wish I’d had an inkling of what they would become. I was ambitious but didn’t in the slightest expect my photographs to inspire and go all over the world as they have today.

James Barnor's 'Accra/London - A Retrospective' is on view at the Serpentine North Gallery, London from 19 May until 22 October 2021.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 219 with the headline ‘Interview:James Barnor’.

Main image: James Barnor, AGIP Calendar Model, 1974, photograph. Courtesy: the artist and October Gallery, London

Thumbnail: James Barnor with his photographs, Accra, c.1952. Courtesy: the artist and Autograph ABP, London