Robert Longo: ‘Montage Is a Way of Living’

Ahead of an exhibition at Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac in London, the artist reflects on John Berger’s influence and embracing ambiguity

Ahead of an exhibition at Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac in London, the artist reflects on John Berger’s influence and embracing ambiguity

Emerging in late 1970s New York as a key figure in the Pictures Generation, the American artist Robert Longo is celebrated for an expansive, multi-disciplinary oeuvre that interrogates what he has termed the ‘image storm’ that engulfs our daily lives. Perhaps best known within the art world for his monumental, hyper-realistic charcoal drawings, which depict striking, often politically charged imagery gleaned from sources ranging from news reports to the art of the past, Longo has also reached a broad audience through his work as the director of the celebrated music video for New Order’s Bizarre Love Triangle (1986), and the cyberpunk action film Johnny Mnemonic (1995), recently re-released in black and white. Tom Morton caught up with him as he prepared for a two-part solo exhibition in London at Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac and between his retrospective at the Albertina Museum in Vienna and a survey at the Milwaukee Art Museum.

Tom Morton Can you tell me about your two London shows?

Robert Longo Since the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve been putzing around. I have a studio in my house in East Hampton and one in California. I experiment, and nobody ever sees what I’m doing. I’d visit this little store that sells shitty old used paperback books, where I found a copy of John Berger’s Ways of Seeing (1972). I remembered this book’s importance to us in the late 1970s, when the whole thing with the Pictures Generation happened. I was thumbing through it, then I went back and watched the television series Berger made on the same subject. I thought, maybe this is a new beginning, a chance to combine Berger’s ideas with those of the filmmakers Andrei Tarkovsky and Sergei Eisenstein. I had always been interested in montage. I view these London exhibitions like walking through a gigantic, epic movie. When I first started to produce my original ‘Combines’ (1981–89), I was trying to make frozen movies. These shows in London contain new ‘Combines’.

TM How do these new monumental, five-panel multimedia wall pieces relate to your previous work?

RL I exploded with the ‘Men in the Cities’ (1977–83) series in the late 1970s and early ’80s. They became so successful that they entered the culture in a way that caused me to lose authorship. They became iPod ads, fashion ads. I intended viewers to see ‘Men in the Cities’ as a series of images. I always wanted them to be like a guitar chord in a Sex Pistols song – an abstract symbol. Afterwards, I forced images from different sources together and made these ‘Combines’. Between 1981 and 1989, I made about 25. And then, the end of the 1980s happened, and, I guess, Jeff Koons happened. I got forgotten for a while. I was one of the artists blamed for the ’80’s.

After making Johnny Mnemonic I returned to the studio. I was lost. I had three sons, and I started realizing they were watching television all the time and how much shit they were seeing. I realized I should mediate this phantom empire of images. Pick one image daily to make that image accountable or atone. I did the ‘Magellan’ (1996) series, which contained 366 drawings – one for each day of 1996, a leap year. Now, I think the charcoal drawings have kind of run their course for me, although I’ll probably continue to make them because the world keeps delivering images to me that I have to contend with. So, I wanted to go backwards to go forward. I went back to the ‘Combines’.

TM The two-part show is called ‘Searchers’. I wonder if there’s an evocation of John Ford’s western, The Searchers (1956), in that title.

RL During the 1980s, I curated a bunch of younger artists’ exhibitions. The last one I did was called ‘Searchers’, exploring the idea of artists being searchers. I thought I should use that title for myself. I considered using an image of John Wayne in my work for the London shows, but I wanted to disconnect myself from the movie to a certain extent.

TM I’m interested in both parts of the exhibition following the same format. Should we read them as a single show, as fraternal twins?

I deliberately want these ‘Combines’ to refuse to become coherent narratives

RL Yes, it is one show. Going back to Berger’s Ways of Seeing, I made a rule for myself to make a ‘Combine’ from a drawing, film, painting, sculpture and photograph. So, each exhibition has one of these, and each work is kind of like a body. The first panel of Untitled (Pilgrim) (2024), the ‘Combine’ on view at Thaddaeus Ropac, for example, features a charcoal drawing of the head of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s marble altarpiece sculpture The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1647–52). Next to it is footage of a fire on a video screen behind a cut-out steel plate. The middle panel is a painting, but it’s also a print of this crazy Chanel ad that I saw wrapping The New York Times. The fourth panel features bronze tree branches, and the fifth an image of an iceberg.

TM This seems to relate to Berger’s ideas. A drawing demands a different way of seeing than a sculpture or a photograph, and this is, in a sense, destabilizing. We can’t quite reconcile the bodily elements you offer us, can’t consume these ‘Combines’ in a single ocular bite.

RL Exactly. When you’re in a museum and looking at a painting, there’s another painting next to it. Montage is a way of living. How do you navigate the world? How do you navigate all these images? The ratio of each panel in my new combines deliberately echoes that of a phone screen. The idea is that you’re swiping, a bit like a highly curated Instagram.

TM That technology wasn’t there in the 1980s. So, is there a point of distinction between the ‘Combines’ from the earlier period and those you’ve been producing recently?

RL Yes, but the images have always been there. They’ve been in movies, in cinema. They’ve been in art. And the advancements in the remote control that led to channel surfing in the 1980s is now our version of swiping on Instagram.

TM Looking at the two ‘Combines’ at Pace and Ropac, while Untitled (Hunter) (2024) seems concerned with human violence and political struggle, Untitled (Pilgrim) (2024) feels more focused on material ambiguity and transience. There’s even hint at the metaphysical, in the drawing of Saint Teresa experiencing an ecstatic religious vision. Can you speak to this difference?

I’m a chronicler of the times that we live in

RL I deliberately want these ‘Combines’ to refuse to become coherent narratives. I want you to go, what the fuck? What does this have to do with that? So, ultimately, what you see in these five images in front of you is one picture, and you’re putting that together in your head. I hate the idea of pastiche or collage. These are more like collisions or car crashes.

TM Collision suggests violence. Can this be a productive force?

RL Well, violence, sex, love and happiness are all aspects of life at a heightened moment, outside the everyday. These are moments of hyper-realism, which is interesting to me. The images are all chosen intuitively, but they’re based on collective knowledge. The essential thing is that they’re highly personal but also socially relevant. I’m interested in poetic images, in emotional flow. I’m highly suspicious of shit that makes sense. I don’t want to make sense, man.

TM And why are you suspicious of things that make sense?

RL Look at the world, man. Really, what the fuck?

TM I wonder if I can take you from there to Untitled (July 4, 2024; Chapter One) (2024), a video featuring a hyper-accelerated loop of thousands of news images from a single day, the 4th of July 2024, which is screening in both shows?

RL I was thinking about the insane number of news images we see all the time. Part of my job seemed to be negotiating these images, and making them atone, taking a split second and making it forever. The film has no beginning or end. When it’s projected at Pace it will be 10.6 by 3.6 meters. At Thaddaeus Ropac, it will be the size of a smartphone on the wall. It will just run endlessly. And this is chapter one – I'll continue to collect and collate images. Ultimately, there will be one year’s worth of this stuff.

TM Like the film, your large charcoal drawings such as Untitled (Wisteria) (2024) at Thaddaeus Ropac, and Untitled (Black Peony) (2024) at Pace seem much concerned with time. They use a centuries-old medium to reflect on contemporary image culture. They also take many long hours to make.

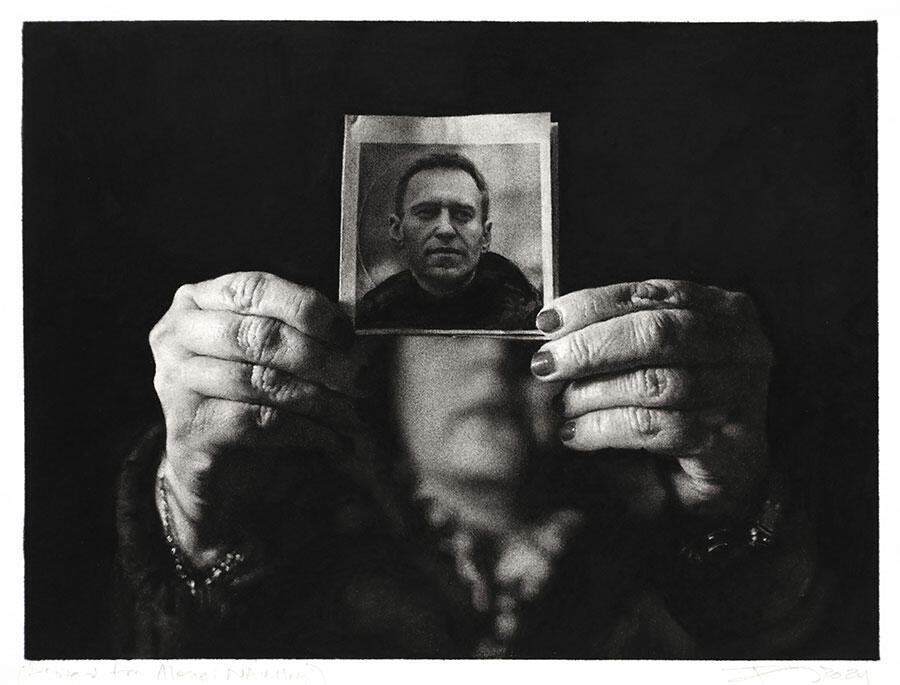

RL Just like waves and bombs, flowers are the moment of their being. Every time you look at these flowers, they’re blooming. Myths happen every time we tell a myth. I want my work to happen every time you look at it. There are also two small drawings of protests. There’s one of the activist Mahsa Amini, whose suspicious death in Iran in 2022 ignited the Women, Life, Freedom movement. The other one is of former Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who died in prison in 2024. Both images are being held in the hands of an elderly woman, which I thought was quite profound. They’re tiny images on the wall, like ghosts, and I want to haunt the other pieces with them.

TM Your London shows occur between two other significant exhibitions: a retrospective at the Albertina Museum, Vienna, and ‘The Acceleration of History’, an exhibition of work since 2014 at the Milwaukee Art Museum. What has that experience been like for you, looking back at work you made as a younger person at a different time?

RL I realized how much technically better I’ve become. The ‘Men in the Cities’ are pretty primitive. My work now has transcended the expectations of the medium of drawing, and I consider them to be in the tradition of history painting. You have the world and then the representation of the world. I’m trying to navigate that. I think I’m a chronicler of the times that we live in. I think all art is an indicator of the time when it happened. Looking at Caravaggio or Rembrandt, you can see what life was like then. You can get a sense of it. I think this is important. God knows what my work will seem like 100 years from now, if we’re still around. The idea of being an artist is this desire to share. I think that’s important. I want to make pictures that matter, I don’t want to make decorations. I always go back to what Pablo Picasso said: it’s not to hang on your wall. It’s a weapon.

Robert Longo’s ‘Searchers’ is at Pace and Thaddaeus Ropac, London, until 09 and 20 November, respectively. His retrospective is at the Albertina Museum, Vienna, until 26 January, and ‘The Acceleration of History’ is at the Milwaukee Art Museum until 23 February 2025.

Main image: Robert Longo, Rendering of Untitled (Hunter), 2024, Mixed Media, 5 parts [dye sublimation print, plexiglass, 3D color print, video, and charcoal on mounted paper], 224 × 750 × 15 cm. Courtesy: © the artist and Pace