Jamie Fitzpatrick

Vitrine, London, UK

Vitrine, London, UK

London’s Vitrine, after flirting with an additional, more orthodox location in 2012–15, has reverted to showing behind a 16-metre glass frontage on Bermondsey Square. (The gallery will open a new space in Basel in April.) It’s not an obvious setting for sculpture – though viewable 24/7 from the street, works can’t be seen in the round – but Jamie Fitzpatrick relishes it as a stage-like setting for his inherently theatrical work.

Fitzpatrick received his MFA from the Royal College of Art in 2015 and has recently been included in significant group shows including ‘UK/Raine’ at Saatchi Gallery and Bloomberg New Contemporaries. It’s easy to see why he has drawn attention: there’s an in-your-face swagger to his artfully messed-up figures in wood, wax and polyurethane foam and their intermittent motorized movements draw further surprised attention. His visual language originates in a critique of public sculpture, which Fitzpatrick sees as having lost historical context: as the great individuals represented fade from the collective memory, statues remain as general symbols of systems of social privilege.

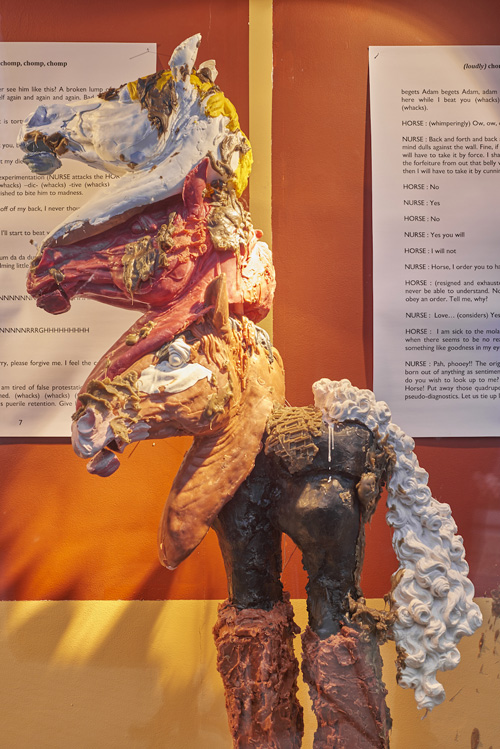

(loudly) chomp, chomp, chomp is a three-part play written by the artist, with its sculptural protagonists set against the backdrop formed by the ten-page script, which has been printed onto giant sheets. According to Fitzpatrick’s text: ‘A GENTLEMAN of some standing has been unsaddled from his HORSE. This fall has left him in a state of irrecoverable illness. A NURSE has been charged with the job of facilitating him back to health.’ The text behind the tableau informs us that the horse, having borne a historically important man for some centuries, has taken the chance to bite his burden, who has been thus reduced to legs and a head. The meal has given the horse severe indigestion. The nurse has no sympathy for the animal and concentrates on a plan to fill the gaps in her master’s flesh with manure. The horse, though, resists the urge to defecate and so she beats it. The horse gives in eventually, but seems to escape – whether into death or the distance isn’t clear – at the end of the scene. The stage is flecked with excremental brown lumps and every now and then the nurse’s mouth gapes, the horse’s jaw chomps and the gentleman presses a comically long nose against the window as though both thumbing it at us and mocking our noses-against-glass voyeurism.

Fitzpatrick ridicules what he terms ‘the arrogance of permanence’ in the gentleman – and, by implication, authority figures in general – by establishing multiple contrasts with the conventions of memorial statuary. His figure is elevated by neither horse nor pedestal; is made mostly of transitory and base materials with a shoddy, even ugly, aesthetic; has exaggerated proportions and missing body parts; is confined behind glass; makes twitchy, cheekily irreverent mechanical movements; and acts out a demotic text.

All of this generates some energy, but neither approach nor theme is particularly new. The aesthetic is a mash-up of Paul McCarthy and Phyllida Barlow, and the pomp of historic statuary is both an easy target – who, now, upholds the colonial values it typically embodies? – and one which has been widely tackled. Consider, for example, the work of Hew Locke and Folkert de Jong, or the commissions for the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, almost all of which have had an aspect of such a critique. Moreover, MeeKyoung Shin’s Written in Soap – A Plinth Project in Cavendish Square (2013–ongoing) – which recreates the site’s original but long-gone sculpture of the Duke of Cumberland in soap – is a more direct way of addressing the mutability of history’s judgements about who is important.

Nonetheless, Fitzpatrick mashes up his sources up with verve and brio, and puts a fresh emphasis on the theatrical. The artist has spoken of plans to create audio texts for his acting sculptures, for example, which might suit more direct and current political content. Certainly, it will be interesting to see where he goes from here.