Janiva Ellis Challenges White Supremacy’s Influence on Visual Culture

At the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, the artist presents a suite of new works that confronts the notion of 'white angst' in western iconography

At the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, the artist presents a suite of new works that confronts the notion of 'white angst' in western iconography

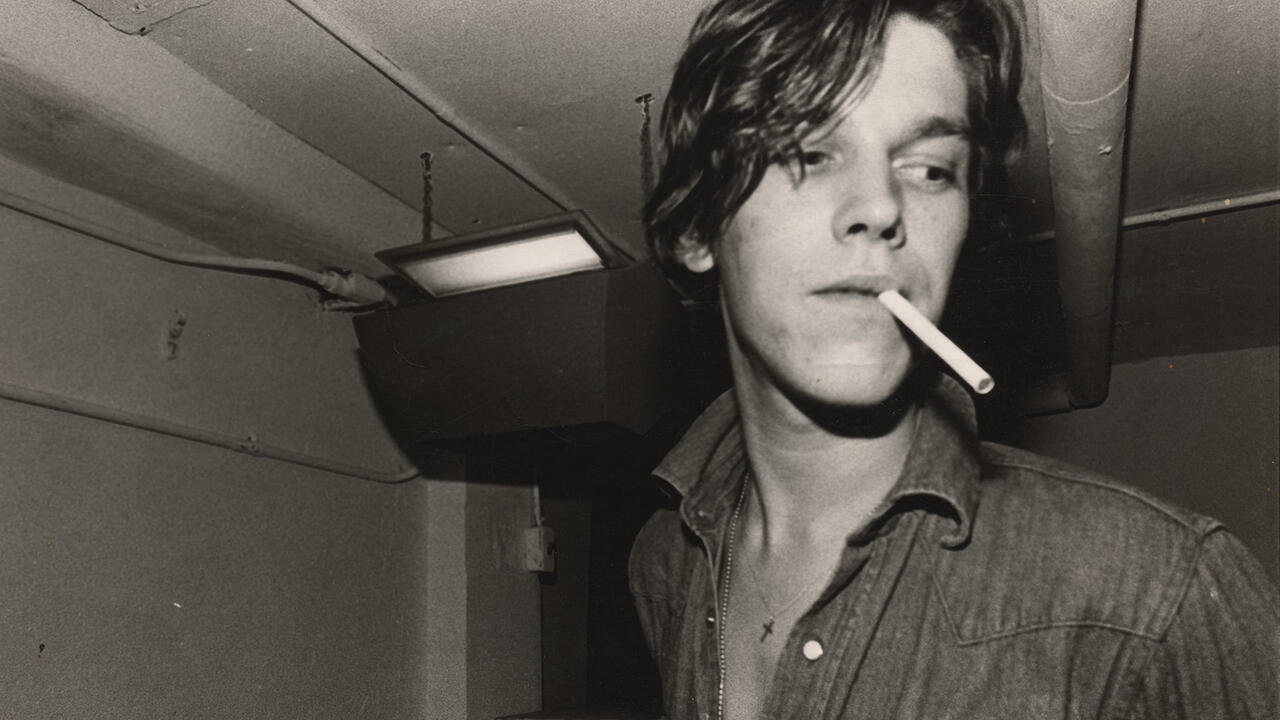

At first, I read the figure glaring from the ledge in the corner of Janiva Ellis’s churning history painting, The Alleyest-oop (2021), as the girl on the curling cliff from the album art of Korn’s Follow the Leader (1998). That’s misremembered, but not wrong: the Korn girl has a red dress and pigtails; Ellis’s cropped-haired figure sports a white t-shirt and jeans so flared you could fit a textbook in the pocket (i.e. the uniform worn by middle schoolers who listened to Korn). The painting is based on a Golgotha scene in Fernando Cabrera Cantó’s Al abismo (To the Abyss, 1906) where the damned fall into hell but, in Ellis’s rendering, the pile of flailing, naked souls gather aimlessly as if in a mosh pit. Where the cross would be, this JNCO-clad youth observes the sheeple below with a cartoon smirk. The dreadlocked white angst of nu-metal repeats the way that white suffering and its formalist execution in paint overlap and feed one another in Western art history, as if the pale young Jesus allowed himself to hang mostly so there would be crucifixion paintings – a gesture as performative as Jackson Pollock’s piss-like drips.

Too much? But there’s more. Ellis’s ‘Rats’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami, her first solo museum outing, is dominated by heroically sized, glistening oil paintings thick with references to the Western canon. The heaviest example is Hollow Provocation (2021) – a fiercely chunky, semi-abstract mecha in army green cradling a shrivelled pink human – that riffs on Robert Motherwell’s series ‘Elegy to the Spanish Republic’ (1948–67). This invective moves cruelly, intimately in Bloodlust Halo (2021), where Ellis has closely re-created the grisaille composition of Walker Evans’s photograph A Child’s Grave, Hale County, Alabama (1936), adding an intestinal rose screed to its row of desaturated votives. Evans’s original photo appeared in his and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), a landmark publication of leftist art and sociology that depicted poor, white sharecroppers – to the omission of equally poor, perhaps longer-suffering Black ones. Agee’s tormented text summarizes the racial dynamics of the day in an anecdote about a Black couple who, when the two white journalists approached them, ran in fear.

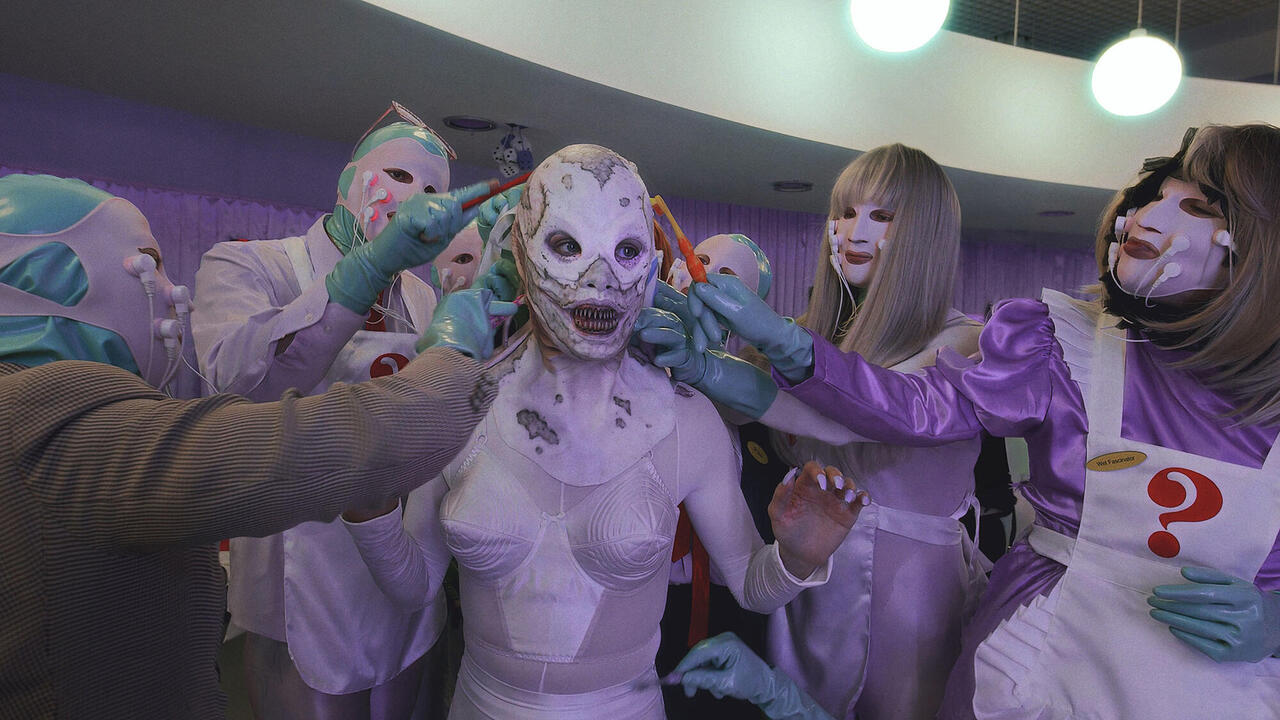

It’s fitting that the show’s few portraits – three mid-sized canvases depicting Black figures and faces – occupy a square room-within-a-room, half-lit through a low, linen ceiling. This separation implies a kind of self-assurance on the part of the artist, as if she can wield all this white chaos, but would prefer not to. In a work with the brilliantly prepositional title Plaguing in my Face (2021), the mind forms the missing word: ‘rats’ – and, indeed, the snarling face in the painting serves as the floor for a crazed rodent dance, like angels on a pin or plague rats fleeing a ship, yet equally evocative of the Disneyfication of blackface in Mickey Mouse’s debut, Steamboat Willie (1928). Here, it’s not the fact of pain or the skittering cloud of references and refrains that is heroic so much as it is endurance, with the extra caveat that painting is its own obstacle. It’s like the title of a small, wiry, horizontal canvas, also in this liminal room, depicting a Black figure seemingly tripping down a pair of cartoon anvils – Something in the Way (2019) – an exasperated declamation, a statement of the obvious and also the name of a 1991 Nirvana song.

'Janiva Ellis: Rats' at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, is on view through 12 September 2021.

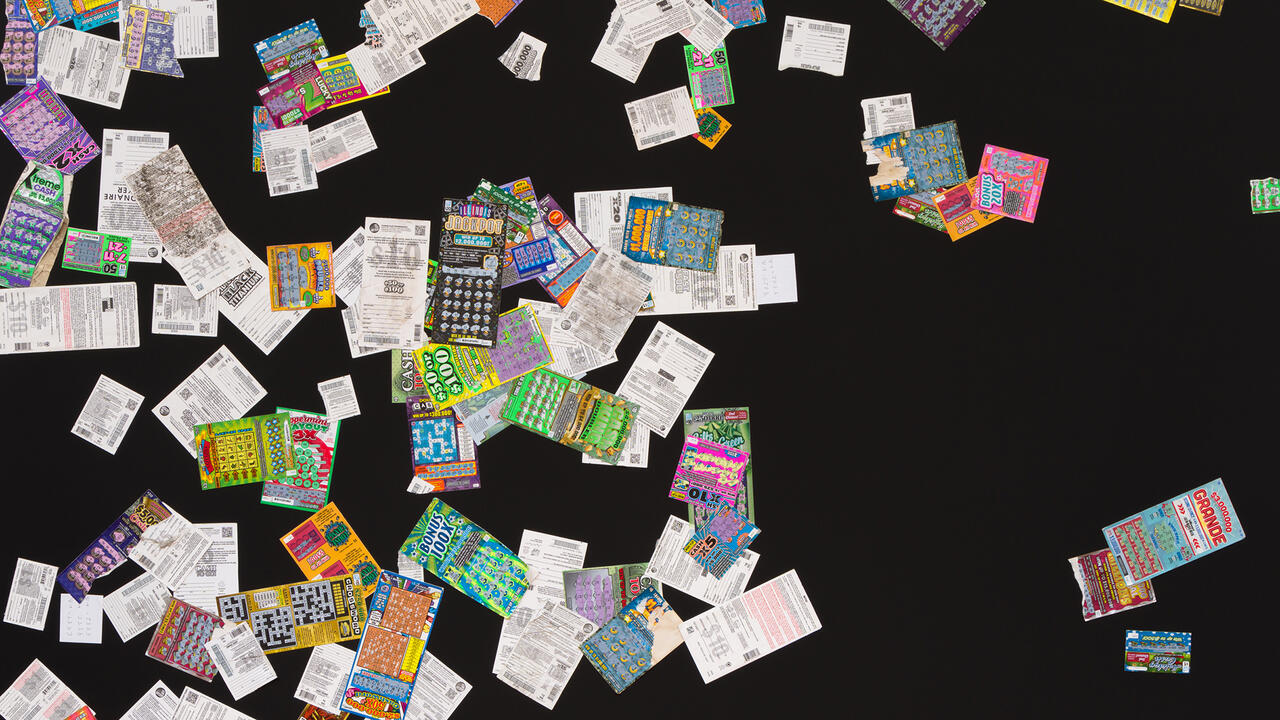

Main image: 'Janiva Ellis: Rats', 2021, exhibition view, Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. Courtesy: the artist and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami; photograph: Zachary Balber