Jeddah 21,39

The fourth edition sees Saudi artists delivering work that is unfettered, brave and relevant

The fourth edition sees Saudi artists delivering work that is unfettered, brave and relevant

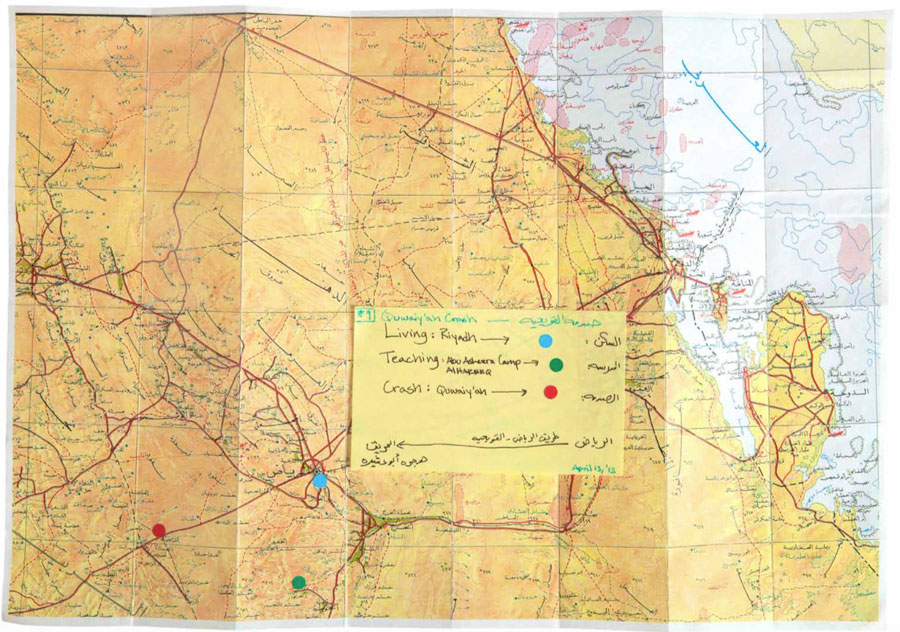

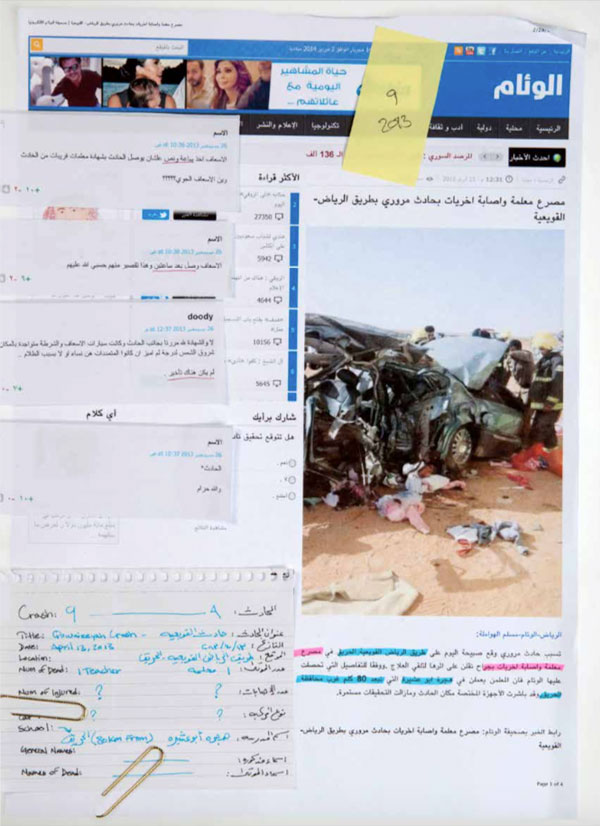

In Saudi Arabia I saw an artwork that has shaken me to the core. The mixed-media piece Crash (2017) by Manal Al-Dowayan is on show in 21,39, the non-profit art initiative which launched its fourth edition last week (it runs until 6 May) in Jeddah, the port city on the Red Sea. Al-Dowayan’s piece – the latest iteration of an ongoing research project initiated in 2014 – explores the controversial issue of female teachers who have died as passengers in car crashes across Saudi Arabia. The oil-rich state, one of the most oppressive on earth, is the only nation that bans women from driving. Yet, due to a policy of providing state-funded schoolteachers to even the most rural villages, many teachers are forced to make long commutes.

The media never mention the victims’ names, says Al-Dowayan, who has included a news report and photographs in her piece. The installation, with its statistics detailing the number of accidents per city (17.5% in Riyadh) and a ghoulish video of a woman declaring her own death, is at times a little laboured. But seeing something this incisive in Jeddah was revelatory.

There are plenty of works in 21,39 that are as adroit as they are provocative. Much of this is down to the independent curators, Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, who have organized the annual event encompassing exhibitions across three venues, educational workshops, and an excellent talks forum (visits to artists’ studios and commercial gallery openings are also in the mix).

Bardaouil and Fellrath have shaped the show around the theme of safar, the word for travel or journey in the Arabic language. The curatorial framework ‘highlights this edition’s focus on education and discovery’, they say, which sounds banal on paper but is a master-stroke in practice. The pair has overseen new commissions by 17 emerging Saudi artists on view at The Mall space located in the Gold Moor Centre, a shopping centre in the city’s Al Shate’a district.

In this incongruous and strange setting, artists have astutely shaped and reconfigured the space (rarely is the term ‘immersive’ a justified epithet but it is apt here). These works are rigorous in a way, reflecting practices that are still raw but becoming more refined. Moath Al-Ofi’s photographs of shepherds practising their ancient profession on the outskirts of the holy city of Al-Madinah Al-Munawarah (The Shepherd, 2015/16) look rough-hewn but reveal real empathy for the subjects’ other worldliness.

Negating one’s heritage is not an option in this context. Zahra Al-Ghamdi’s The Labyrinth and Time (2017) is a large-scale, site-specific sculptural work moulded from sand, cotton and water that mimics the forms of historic houses found in Al-Balad, Jeddah’s historical downtown district. The tangled topography is an aesthetic accomplishment but also a transitory marker of the city’s memories.

Nasser Al-Salem, a Jeddah-based architect, expertly mines the past, pushing, as he says, the age-old Islamic art of calligraphy by exploring its conceptual potential. Such a claim may sound trite but his three-dimensional structure, They Flaunt their Buildings (2017), is a feat of engineering: Al-Salem has drawn on his calligraphic training to turn an ancient saying (yatatawaluna fil bunyan, their buildings reach higher) into a series of architectural building blocks. It is a stupefying sight – where to start in interpreting this monolithic mass? From the ground where it appears impenetrable, or in the mirror above where the form takes shape as a legible turn of phrase?

Nothing quite matches the spectacle though that is Suspended (2017), Abdullah Al-Othman’s site-specific work located in Al-Balad, Jeddah’s historic downtown district. Al-Othman has wrapped an entire building, originally used as a shelter for widows and divorced women, in tin foil. This Christo-esque act is both startling and serene: encasing the 200-year-old property in a flimsy metallic layer, which is slowly disintegrating, makes temporality strikingly corporeal. It is the most dramatic, adept and dispiriting gesture.

Al-Othman’s work is the most visible artwork in the 21,39 festival, and residents are fascinated by the shiny relic (this piece is a very public beacon, but let’s hope local audiences will feel emboldened enough to attend the other exhibitions in the festival, otherwise 21,39 will be nothing but a triumph of soft power aimed at a delegation of foreign visitors).

The show is not, however, confined to local practitioners. A video and new media exhibition at the King Abdullah Economic City complex north of Jeddah, billed as a first for Saudi Arabia, includes works by ‘eight leading international artists’ according to the catalogue. William Kentridge, Anri Sala and Douglas Gordon are among the big names on the roster.

Gordon's Play Dead; Real Time (2003), which shows melancholic Minnie, a four year old circus elephant, lumbering around Gagosian gallery, is as elegiac as ever. Shirin Neshat's Rapture (1999), peopled with rival choruses of chanting Muslim men and women, takes on a new dimension in Saudi where the sexes are set apart. But nothing is as piquant as the works by the emerging Saudi artists who have delivered something more unfettered and relevant than expected at 21,39; in Jeddah, this really was unexpected.

Main image: Reem Al-Nasser, The Silver Plate (detail), 2017, film still. Courtesy: the artist