The Pleasure Principle: The 57th Carnegie International is Beautiful but Safe

The second oldest exhibition in the world, held at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, makes the case for ‘museum joy’

The second oldest exhibition in the world, held at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art, makes the case for ‘museum joy’

It’s back to basics for Ingrid Schaffner, the curator of the 57th Carnegie International: her stated aim for the august quinquennial, which opened last weekend in Pittsburgh, is to inspire ‘museum joy’. Inked in curlicue script on museum tote bags, it’s a twee catchphrase for this generally twee exhibition, one which – depending on how quickly you dismiss it – may reveal something about your own position in (or outside of) the art world. With no discernible theme and a starry list of 32 artists and collectives, this show will disappoint critics hunting for contention, and bore the biennial circuit in search of the next best thing. Instead, it is buoyantly beautiful, unashamed to favour the aesthetic over the conceptual by its meticulous attention to visual detail. A feast for the eyes, it may nonetheless leave you hungry for substance.

A colourful curtain of cut paper and metal drapes the boxy, mirrored façade of the Carnegie Museum of Art’s Scaife wing, designed in 1974 by Edward Larabee Barnes. A monumental tapestry by El Anatsui (Three Angles, 2018), it’s a confetti-canon welcome to the show. The second-floor galleries open in even more exuberant fashion with ceramics and tapestries by Ulrike Müller, whose work has never looked better. Their bold tones and subtle textures pop against charcoal grey walls, which harmonize with Sarah Crowner’s scintillating Wall (Wavy Arrow Terracotta) (2017), a large band of aquamarine tiles resembling fish scales that extend through the wall into the foyer. (There’s ‘museum joy’ here aplenty.) In the following gallery, a large selection of new paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye sing against walls the colour of custard. Though all depict fictional black characters in casually elegant poses, with brushwork that seems almost effortless, some seem unusually dreamy: a woman hazy behind a snaking trail of cigarette smoke, or two men, dressed in feathered leotards, crouched like handsome crows.

These spacious installations are each accompanied by just one single ‘tombstone’: a label bearing the artist’s name, their work’s title and the date of its completion. For longer texts, a number directs you to The Guide, a precious notebook designed by Prem Krishnamurthy and Max Harvey. Its introduction is one of the most refreshingly frank and accessible texts about curating that I’ve read in a very long time. In a section called ‘Customs’, it addresses simple yet important facts, like the median height at which works are hung (‘low at 58 inches, and high at 61’) and the temperature that best preserves them (68 to 72 degrees Fahrenheit). It also offers some bold advice: ‘To approach the exhibition with confidence, travel light. Burdensome cultural baggage comes in all forms, from fanny pack to portmanteau.’

It’s a disarming request, but one that presumes prejudice rather than prior knowledge. The viewer Schaffner has in mind doesn’t look at much contemporary art and is repelled by institutional jargon. While many curators could learn from studying her language, it sometimes risks oversimplification. Cultural baggage, or at least background knowledge, seems essential when appraising the pairing of Indian artist Dayanita Singh with Pakistani-born American artist Huma Bhabha: as Bhabha’s haunting, phaoronic polystyrene figure confronts Singh’s wooden towers framing photographs of archives, it’s unclear why the show’s only two artists born on the subcontinent were made to re-enact some kind of Partition. There are other essentializing gestures: a stunning suite of intricate watercolours depicting jungle plants and animals by Abel Rodriguez, an elder of the Nonuya people from the Colombian Amazon, appears alongside a pop-up café by the Vietnamese collective Art Labor festooned with paper kites hand-painted by Joan Jonas, their designs referencing the foliage of Southeast Asia. Tropical affinity, though sensually pleasing, offers little insight into either project.

The most bewitching project in the show emanates a glow beyond the doorway to its gallery. Alex Da Corte’s Rubber Pencil Devil(2018), a steel frame cottage lined with lurid neon lights, serves as a theatre for short music videos that feature the artist and a cast of pop characters, from Bugs Bunny to Charlie Brown. There are 57 videos in total, for the 57th Carnegie and the famous ‘57 Varieties’ of Heinz, the ketchup empire that shaped Pittsburgh nearly as much as the steel industry. Da Corte also plays Mr. Rogers, the TV personality whose beloved children’s show was broadcast from a nearby studio for nearly 40 years. In each episode, Rogers made a ritual of removing his shoes and sweater, and so Da Corte repeats the act ad infinitum, his sweaters changing colour with each cycle. The gesture feels laughably absurd yet strangely melancholy, like a play by Eugène Ionesco.

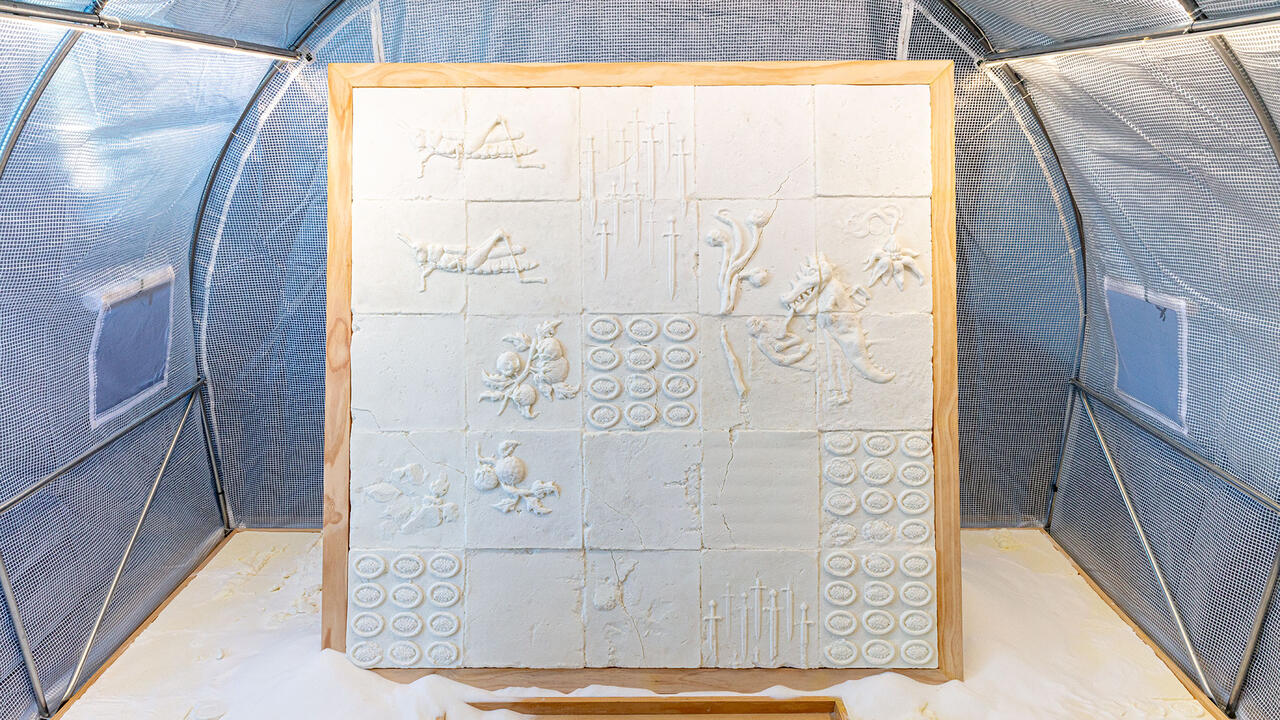

A new series of photographs by Zoe Leonard cast an even greater spell with far fewer means. Prologue: El Rio/The River (2018) depicts the surface of the Rio Grande, stippled and grey like an elephant hide. Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn admires navigators who can read messages in the river; the water in these photographs, which nurtures an ecosystem while severing the US from Mexico, seems both velvety smooth and scarred by eddies that open up to murky depths. Leonard’s river rings the marble mezzanine of a grand neoclassical atrium, whose central court holds an impressive installation by the indigenous collective Postcommodity, inspired by the sand paintings of the Navajo, whose ancestral lands are the source for the mighty Rio Grande. Rendered in coal, glass and scrap metal, the installation – an abstract painting when viewed from the balustrade above – makes oblique reference to Pittsburgh’s industrial past.

That history comes into clearer view in Kevin Jerome Everson’s eight-hour film Park Lanes (2015), which records a day at a factory in Mechanicsville, Virginia. Sounds of hammering and soldering fill the grand, gilded staircase in which it is projected, a welcome reminder of the labour that built the Carnegie Museum. As if to drive this point home, nearby walls bear frescoes of sweat-slicked men stocking Bessemer furnaces, smelting the steel that holds the building up.

Ultimately, though, it’s one of the exhibition’s most distant contributions that best understands this local context. ‘Dig Where You Stand’, a show-within-a-show organized by Senegalese curator Koyo Kouoh, gathers objects from the Carnegie’s collection for critical assessment. Its power throws the quinquennial’s aestheticism into sharper contrast. See, for instance, how a panting of sharecroppers by Thomas Hart Benton (Plantation Road, 1944–45) accompanies a gorgeous watercolour by a sharecropper’s son, Robert Gwathmey (Sharecroppers, 1940–41); or how photographs of smoke-choked 1950s Pittsburgh by W. Eugene Smith face off with snapshots by Charles ‘Teenie’ Harris of black salespeople selling Heinz products at a home fair. The gaze of Western (particularly French) art history is pilloried by both Nam June Paik’s TV Rodin (Le penseur) (1976–78) and Mickalene Thomas’s Le dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires (2010). Female power is on display, meanwhile, in Cecil Beaton’s coronation portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, an Egyptian relief of Isis, and a 1968 Beauford Delaney portrait of Carnegie patron Tillie S. Speyer. Most unsettling of all is the show’s closing work: a fear of peppered moths, pinned to a board, whose gradually darkening wings reveal the effects of industrial melanism – perhaps the greatest proof on display that race is a cultural construction.

In the end, it’s Kouoh, not Schaffner, who proves that an exhibition can look great and have something serious to say. By paying close attention to the details, Schaffner seeks to remind us of the importance of beauty, something those outside the art world have never forgotten. It’s a deeply pleasurable and accessible experience but confronts us with a false choice between surface and substance. ‘Museum joy’ should mean having it both ways.

The 57th Carnegie International runs at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, until 25 March, 2019.

Main image: Alex Da Corte, Rubber Pencil Devil, 2018, installation view, 57th Carnegie International, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. Courtesy: the artist and Karma, New York; photograph: Tom Little