Kandis Williams Links Choreography with Control

At Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna, the artist draws a line from the plantation to the stage

At Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna, the artist draws a line from the plantation to the stage

Kandis Williams’s ‘Notes on Dance’ is less about what dance is than about what choreography shares with artmaking and systems of political oppression: the organizing of bodies in space. Williams thus invokes an analogy between dancers’ regimented bodies and other modes of physical discipline and control, such as prison routines and military drills. For, while dancers may follow choreographers’ instructions to produce symbolic and emotive effects on stage, society is informed by methods of behavioural reform to such an extent that it even percolates into forms of supposedly free self-expression, such as dance. This is a point Williams underscores in two videos on display here, Annexation Tango (2020) and Triadic Ballet (2021), the latter of which is named after, but does not re-enact, Oskar Schlemmer’s eponymous work from 1912.

Annexation Tango shows us a lone male dancer – shirtless, sweat-drenched, barefoot, with bleach-blonde hair – performing a sultry tango, his moving body projected over images of Norfolk, Virginia: its green countryside, vast suburbs, former cotton plantations and huge prison system. It seems, at first, that he’s dancing alone, until it becomes obvious that Williams has removed his partner in post-production, whose figure leaves a translucent trace – an ethereal presence around the dancer’s waist that seems to fragment his body.

Meanwhile, in Triadic Ballet, we see a single woman performing a diverse sequence of dances. The black floor beneath her has been painted with a white square, divided into six triangles, which guide and frame her bodily positions, if not dictating them outright. Behind her is a video screen that shows, alongside other clips, footage of the delirious tap dancing of the Nicholas Brothers, a military parade, the music video for Janet Jackson’s ‘Rhythm Nation’ (1989), in which military-clad dancers perform an exacting routine, and infamous CCTV footage of Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King in 1991.

Williams’s analogy implies that dancing bodies – emblematic here of all cultural free expression, especially when devised or performed by Black people – are exploited by methods not dissimilar to those used in prisons or on plantations, that naked value-extraction is merely covered up by glamorous Hollywood packaging with the Nicholas Brothers and later becomes part of the choreography itself in ‘Rhythm Nation’. Choreography tells dancers how and where to move: their movements are guided by forces that go unseen in the final performance.

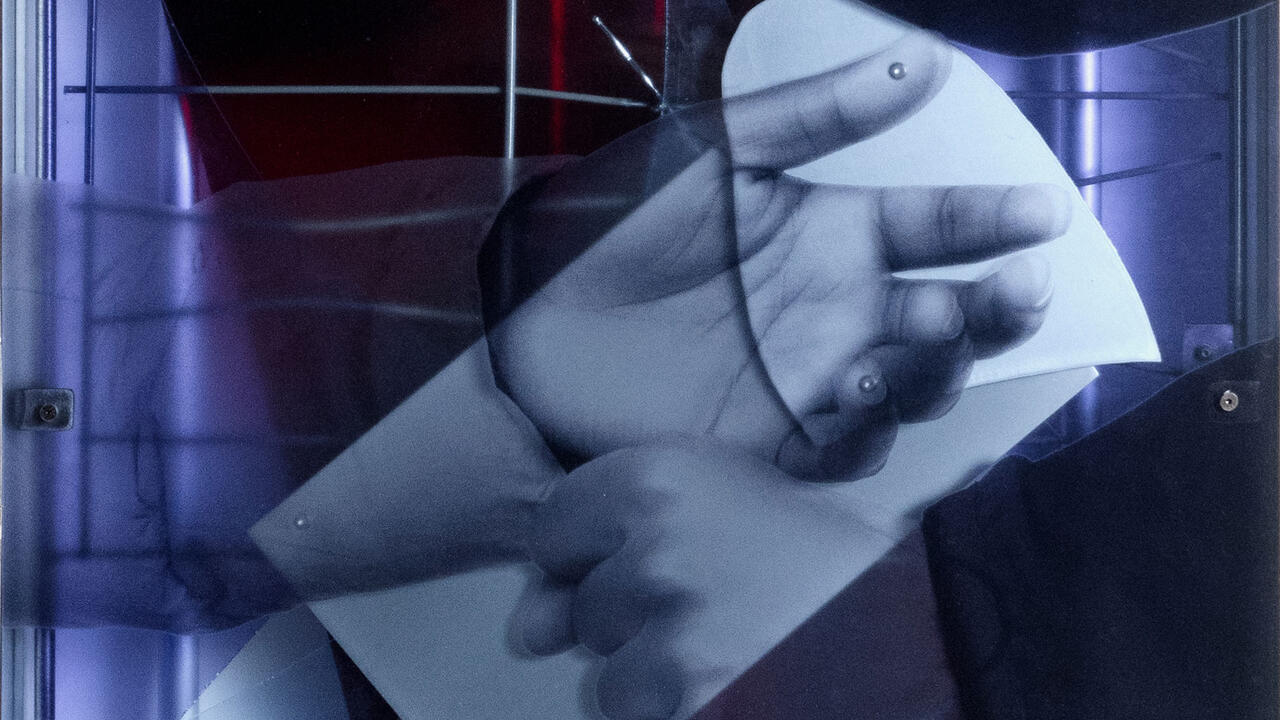

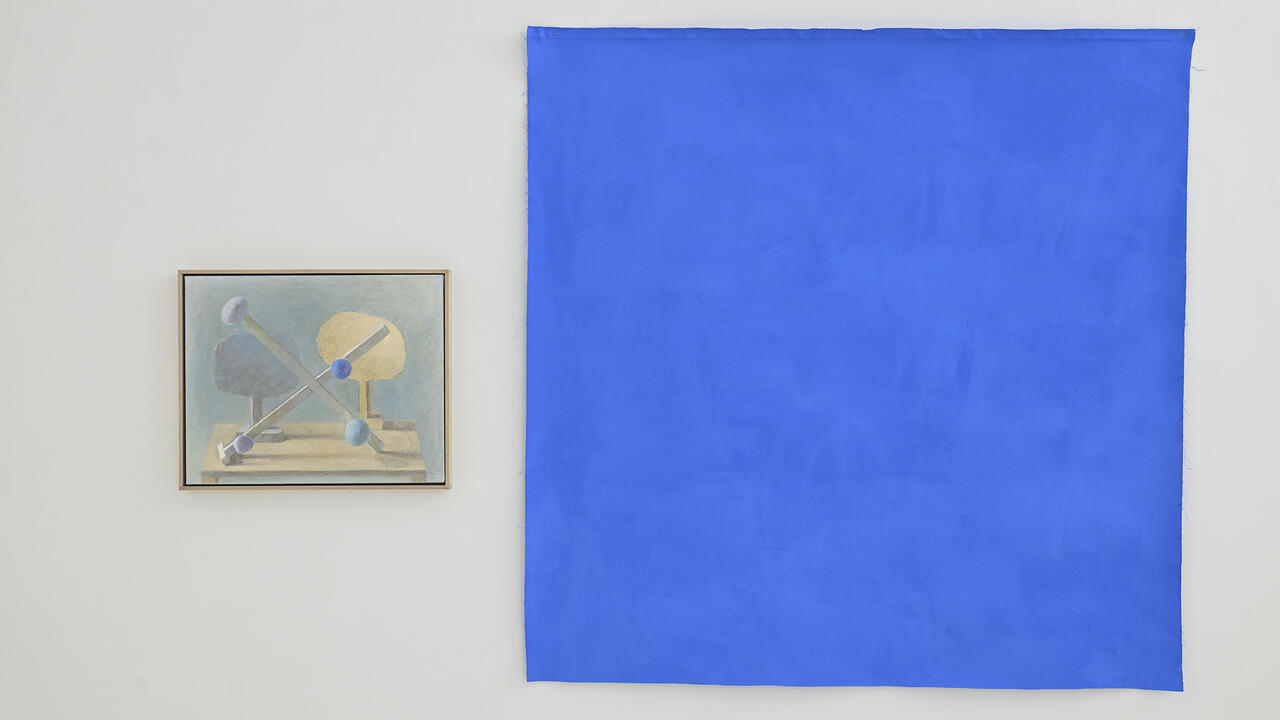

Half of the exhibition’s six photocopied collages – including Extensions available to technique, extensions available to metaphor, extensions available through character (2021) – show us dancers in motion. Williams’s analogy appears here as a method of choreographic combination: images cut from magazines and dance books have been glued onto paper alongside photographs of two Black dancers that she shot in her studio and arranged in clusters. Sometimes, the figures overlap, but the artist still demonstrates a cool choreographer’s gaze, one which positions bodies not just for discipline’s sake, but to inspire viewers to feel something when they see dancers move with grace.

There is, however, a final expression of the analogy here. The collage There Are Two Sides to Every Line (2021) includes images of Martha Graham, the choreography pioneer who employed movements and gestures inspired by – or, more accurately, appropriated from – Black dance. Perhaps Williams is suggesting that such appropriation is comparable to direct forms of exploitation. In any case, Graham’s image represents one aspect of an appalling history, in which creativity born from suffering on plantations or in prison is absorbed by the culture industry, via acts such as the Nicholas Brothers, and eventually repackaged in dazzlingly sinister made-for-MTV military drills.

Kandis Williams’s ‘Notes on Dance’ is on view at Galerie Hubert Winter, Vienna, until 7 June.