Image Ensembles

Conductor-turned-filmmaker, Christian von Borries’s films blend Pop appeal with Capitalist critique

Conductor-turned-filmmaker, Christian von Borries’s films blend Pop appeal with Capitalist critique

Christian von Borries is known as a conductor and deconstructor of classical music. After a career as a solo flautist at the opera house in his native Zurich, he became conductor of the same orchestra. But the prospect of tending the sacred cow of classical music only bored him. He gave up his career and moved to Berlin where, in 1998, he founded musikmissbrauch (music misuse) and, five years later, Psychogeographie. These series of concerts and performances aimed to recontextualize well-known classical music. ‘Misusing music’ meant emancipating oneself from the role of a humble performer of an immutable score, for example by mixing the music with samples or by taking fragments and supplementing them to make new pieces. The autonomous performer is an artist in her own right or – as Von Borries likes to put it more profanely – a ‘user’. ‘Psychogeographie’, in the original sense of this term coined by the Situationist International, dealt with the influence of geography and topography on the listener’s mind: what happens to Mozart if his music is listened to in a public toilet? Or to opera if it is performed beside an autobahn? Inside a former CargoLifter airship hangar near Berlin, for example, Von Borries had the audience pushed around the orchestra in hospital beds. And just before it was demolished, he chose the stripped-out remains of East Germany’s Palast der Republik on Berlin’s Schlossplatz as a performance space for the audience to wander about. All these various projects were about freeing classical music from the moribund temples of bourgeois culture rather than repeating the tired gesture of épater le bourgeois.

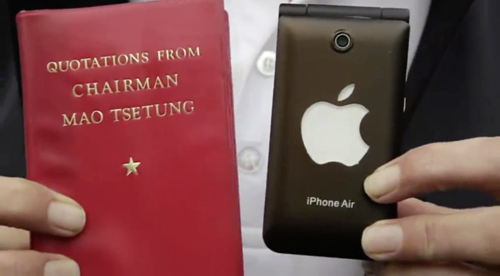

Since 2010, Von Borries has also been making films. He shows them at minor festivals and – as a firm opponent of copyright – makes them available for free via streaming platforms. It’s hard to know what to call them: documentaries? Audiovisual anti-capitalist manifestoes? Potpourris of pop, poetry and politics? Maybe all of these things. Plus, as a vital ingredient, the all-important touch of strangeness, or madness. To date, he has made two features, as well as a short film project with José Elguezabal, and his most recent film, iPhoneChina, is nearing completion. Beyond simply criticizing Foxconn, the company whose factories produce most of our Apple goods, the film also offers a description of a new global form of governance: by software.

Von Borries’s musical engagement with psychogeography is also evident in his films, each of which selects a specific place as a point of departure for political and theoretical reflections. In his debut The Dubai In Me (2010) he describes the largest city in the United Arab Emirates as a huge non-place, in the sense coined by French ethnologist Marc Augé – even if he doesn’t mention him explicitly. Augé distinguishes between organically developed places that have history inscribed into them, and non-places that are not intended to be inhabited, acting instead as functional transit spaces without identity, such as airports, highways or railway stations. Von Borries depicts Dubai as a neo-liberal hell of real estate speculation, full of gated communities, showy company headquarters and artificial shopping paradises. Here, entertainment and the simulation of reality have long since fully occupied the present. ‘I argue that Dubai is a property development company disguised as a state,’ explains the director: ‘one might say that every state has this quality – one has only to think of Deutschland AG or Japan Inc. But in Dubai this phenomenon can be observed in pure, unadulterated form. Based on portrayals in Western media, this interested me.’ The fundamental contradiction identified by Von Borries is between the force of technical innovation driving this futuristic high-rise city and its mediaeval morality. The wealth on display depends on the labour of African and Asian guest workers who are deprived of their rights and obliged to surrender their passports on arrival. Israelis are denied entry. Sharia law applies. Dubai, as Von Borries says in his off-screen commentary, is ‘France before the French Revolution’.

Von Borries’s second film Mocracy – Neverland In Me (2012), which won the Klaus Wildenhahn Prize at the 9th Hamburg Documentary Film Festival last year, does without authorial comments. It looks like one long cleverly edited YouTube symphony interspersed with game and film snippets. Choreographies from videos by Michael Jackson (whose ranch is name-checked in the title) act as a leitmotif. Even hardened browsers may feel queasy in the face of the candy-coloured visual worlds presented here. The film is dedicated to the media theorist Friedrich Kittler and was filmed in locations including Pyongyang, Detroit, Turkey and Kazakhstan. ‘Astana, Kosovo and Berlin. Everywhere the same pattern,’ says Von Borries: ‘city marketing and tourism as a media cover-up for dirty global business’. The interesting thing here is not the obvious critique of capitalism, but the accompanying pop appeal of both the film itself and Von Borries as a person, an appeal seemingly at odds with the usual image of an engaged intellectual and rabble-rouser in the mould of Günter Grass. For all his criticism of neo-liberalism, Von Borries is clearly fascinated by his subject. ‘We can only think about things for which we experience a residue of empathy,’ he says: ‘This kind approach is something I learnt in China, it differs from Western, distinction-based ways of thinking.’ But there is another reason for this pop element in a critical approach that sometimes feels like affirmation: the crisis of traditional left wing finger-pointing. ‘I am interested in the question of how we can talk about these things. In the 20th century, critical theory with its big words failed totally. What are we left with today? We have to find other ways of telling stories that are not based on the top-down model of ‘listen here, I’ll explain it to you’.

His various artistic activities are linked by his use of found footage. He doesn’t draw on the depths of some creative genius. He knows that the death of the author is the birth of the creative compiler. As a composer, his motto was ‘music made from other music’, and as a filmmaker he produces ‘media made from other media’. This leaves no space for notions of authenticity. Von Borries lives in a world of meta- and post-, not because he has read too much Baudrillard, but because he is of his time. And today, that means that anyone wishing to criticize the world must begin by criticizing its images.

Translated by Nicholas Grindell