Leslie Hewitt

The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada

The Power Plant, Toronto, Canada

Occupying three distinct spaces inside The Power Plant, New York artist Leslie Hewitt’s exhibition, ‘Collective Stance’, deftly manipulates the gallery’s architecture to heighten the affective impact of the projections, sculptures and photolithographs on view. Drawing from a collection of civil rights-era photographs held at The Menil Collection in Houston, Hewitt’s show asks viewers to scrutinize still and moving images at a historical remove.

The exhibition opens with Stills (2015), a new collaboration with the cinematographer Bradford Young. On a zigzagging wall, three identical, looped projections play a synchronized sequence of collaged shots of film leader, densely packed skyscrapers and black hands holding a ‘colour rendition’ chart – a reminder that early colour photography processes were calibrated to white skin tones. Soft-edged and interspersed by ‘flash frames’, several of these dreamlike vignettes were recently filmed on 35mm, while other 16mm samples are from the 1970s, some appropriated from the films of Young’s mentor – the pioneering radical black director Haile Gerima. Intercutting past and present, the triptych highlights the tactile materiality of celluloid, with much of the footage marked by dust and scratches. As with her earlier work, Hewitt foregrounds frames within frames to expose how ways of looking are contrived.

The darkened corridor in which Stills plays opens into a large, airy gallery, where five smoothly lacquered, white steel sculptures (Untitled, 2012) reflect the light pouring in through two tall windows. The quasi-minimalist forms resemble cinema screens or oversized sheets of folded copy paper – blank slates awaiting our interpretive projections. A series of modestly scaled photolithographs hang on the walls. The title of one 2012 diptych acknowledges Hewitt’s intensive study of the Menil photographs: Where Paths Meet, Turn Away, Then Align Again (Distilled Moment from over 73 Hours of Viewing the Civil Rights-era Archive at the The Menil Collection in Houston, Texas) pairs two views of the back of a woman’s head, spotted in a crowd, at different magnifications. While the photographs in the Menil archive act primarily to document the civil rights movement, Hewitt isolates and amplifies specific details that are more tenebrous than expository. The gallery’s sparse installation atmospherically evokes an archive replete with ellipses.

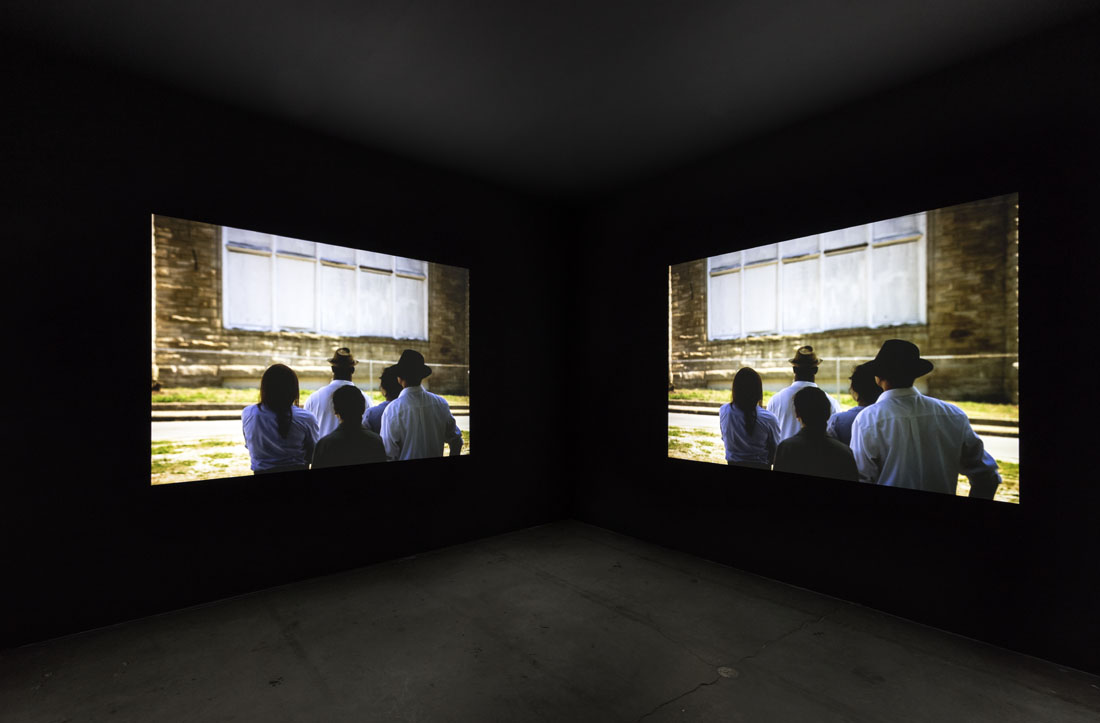

Hewitt’s Untitled (Structures) (2012), an HD dual-projection also produced with Young, concludes the exhibition. Displayed diagonally opposite one another to triangulate the viewer’s gaze, the two 17-minute projections unfold at a steady clip. Figures pose in a variety of exteriors and interiors, including historical sites that played a central role in the civil rights movement, such as the Johnson Publishing headquarters in Chicago and the Clayborn Temple in Memphis. The performers’ gestures recall those of subjects in the Menil photographs but appear frozen mid-action, grafting the stillness of photography onto the motion of film. While these non-linear tableaux were shot recently on 35mm film, they contain a high degree of period detail and beautiful tonal warmth, achieved by modulating light and focus. The spaces’ distinctive architectural details formally echo the frames, screens and grids in many of the other works on view. Traversing geography, history and culture, Untitled (Structures) is expansive; a fragmentary community comes and goes from these fleeting scenes.

Hewitt’s close study in the diptych expands here into a collective grappling with the unfinished legacies of the civil rights movement.Hewitt and Young were both born in the late 1970s and their work necessarily regards the civil rights era with a certain distance and opacity. Their treatment of its historical record conveys how the struggle for black liberation still continues, and that its legacy must be perpetually re-examined. By partnering with an accomplished cinematographer and expanding from still to moving images, Hewitt has found a way of looking askance at the visual archive of black history. Her aesthetic and affective precision reveals it to be a living and evolving memory bank.