Looking Back 2017: Towards a Black Body Politic

A year marked by new visualizations, both controversial and celebrated, of the black body

A year marked by new visualizations, both controversial and celebrated, of the black body

2017 began in the final month of the Met Breuer’s landmark retrospective of some 72 paintings by Chicago’s Kerry James Marshall, and draws to a close with Zanzibar-born Lubaina Himid winning the Turner Prize. The intervening months were, without fail, punctuated by the high-profile exhibition or public recognition (sometimes long overdue) of black artists boldly elaborating and subverting the figurative tradition.

Undoubtedly, portraiture has long occupied a freighted place in the scheme of contemporary art, especially in the realm of painting, which tends to reward abstraction or the merging the medium with forms of linguistic or performative address. Or, as Linda Nochlin argued back in 1971, realist painting has long been seen as the province of the domestic, of women’s labour, even in its most hyper-mediated forms. Things become more complicated when figuring black subjects. On one hand much of the force of various black internationalist art movements since the 1960s has derived from their refinement of a ‘black aesthetic’ and the positive – even heroic – portrayals of black people. Such insistence framed debates around careers as wide ranging as Robert Mapplethorpe and Kara Walker, even as the culture wars of the 1990s further conflated black bodies with either sexual excess or moral danger.

In the era of Black Lives Matter, Brexit, and a resurgent xenopolitics in the West, the time is certainly right to wade back in to the debates. Many of this year’s best exhibitions did just that, highlighting the work of artists who put black bodies front and centre. Kehinde Wiley, for instance, has long been a stalwart of the genre, juxtaposing the European tradition with sitters drawn from urban life, in a simultaneous gesture of appropriating the canonical while elevating black figures to a near-hagiographic kind of beatitude. His summer show ‘Trickster’ at Sean Kelly Gallery was loosely based around a central trope in diasporic religions, and lionized fellow artists such as Wangechi Mutu, Nick Cave, Carrie Mae Weems and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

While Wiley entered the broader cultural context with work featured on, for instance, the hip-hop-infused drama Empire, he became a household name this year when it was announced in October that he would paint Barack Obama’s official portrait. The nod to Wiley was an unsurprising – if important – gesture from a President known for decorating the White House with contemporary art and keeping Jay-Z on his iPod. The selection of Michelle Obama’s portraitist, Baltimore’s Amy Sherald, on the other hand, was more compelling still. Sherald showed new work in a group show at Monique Meloche’s New York outpost in March or her signature style: black figures facing the viewer, pictured from the knees up before a saturated monochrome or subtly patterned background.

Nochlin’s decades-old observation that realism would increasingly mimic the hyperreal – the world as seen through a lens – and re-frame literal objects in subtle ways seems to hold true for Sherald’s array of everyday people. There is an uncanny flatness at work, of a piece with recent graphic design and directorial forms of photography. But that flatness yields a stillness that calls forth something vital about the sitters. If Wiley’s is a blend of baroque lighting and bling excess – what historian Krista Thompson has called the ‘shine’ at work in black visual culture – Sherald’s palette is muted, restrained, but somehow more vivid in spite (or because) of its economy of means.

Of course, Nochlin was writing in parallel with Jeff Donaldson and Romare Bearden, titans of figurative work who elaborated a form of augmented reality called ‘the super real’. That is, the banality of black life by the 1960s was anything but, and everyday images could crystallize imminent but invisible energies, be they spiritual, surreal, or psychedelic. This is the terrain charted in three of 2017’s finest shows: Jordan Casteel (at Casey Kaplan Gallery), Toyin Ojih Odutola’s mid-career ‘To Wander Determined’ at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s ‘Counterparts’, a small suite of large-scale interiors at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Casteel is on track for a meteoric rise, and her Harlem street scenes amplify the pedestrian and exude near hallucinogenic intensity. Odutola, who has steadily built a repertoire of figures braided from shimmering, fibrous material brought her charcoal and pastels into a greater chromatic range to depict two upper-class Nigerian families. Crosby was named one of the year’s ‘MacArthur Geniuses’, and her tableaux update tropes of the domestic, balancing dense patterning stirring lighting effects to complicate hierarchies of location and genre. The latter seem to knowingly cite Bearden and Marshall, but are striking in their originality – they present nothing less than a new vision of American subjectivity, one that is from the outset plural and dynamic.

For all of the prominence of black figuration in 2017, the weight of history was always present either in the background, or woven into the substitution and reclamations staged in the pictures themselves. A crucial issue in that history is the way in which black bodies are represented and, indeed, by whom. One version of this story played out at Hilton Als’ show of vintage paintings by Alice Neel of ‘Uptown’ New York around the mid 20th century. These smaller works show Neel immersed in her Harlem community, and counterbalancing the expressive maximalism of the era with patient and poignant images of subjects typically hidden from view during a time of more overt segregation. The other version came in March at the Whitney Biennial, as a likeness of Emmett Till in his coffin was included in a series of abstract paintings by the white painter Dana Schutz.

The ensuing debate generated productive debate around the limits of appropriation and the dangers of censorship (perhaps best spelled out by Coco Fusco). Either way, the incident was a reminder of the power of images as metonyms for larger cleavages in national life. The case of Till has long animated exhibitions centered on representations of black subjects and persists as an image that reminds us of collective work that remains to be done. Whatever one’s position on the ownership of such an image, Schutz’s orphistic rendition somehow made its subject matter less potent, a clever readymade for a slapdash painting.

More illuminating figuration could be found elsewhere, where 60 year-old Los Angeles painter Henry Taylor was the breakout artist of the Whitney show; his portrayal of an unarmed Philando Castille – shot and bleeding in his car – was both humane and sobering, a reminder of how little has changed since Till’s death in the summer of 1955. bell hooks once wrote of the ways in which white patriarchal dominance is mediated by images of black bodies. She called for something else, suggesting that ‘a revolutionary visual aesthetic must emerge that reappropriates, revises, and invents, that gives something new to look at.’ hooks is arguing here for new visualizations of a ‘black body politic’ and, in 2017, that body politic arrived.

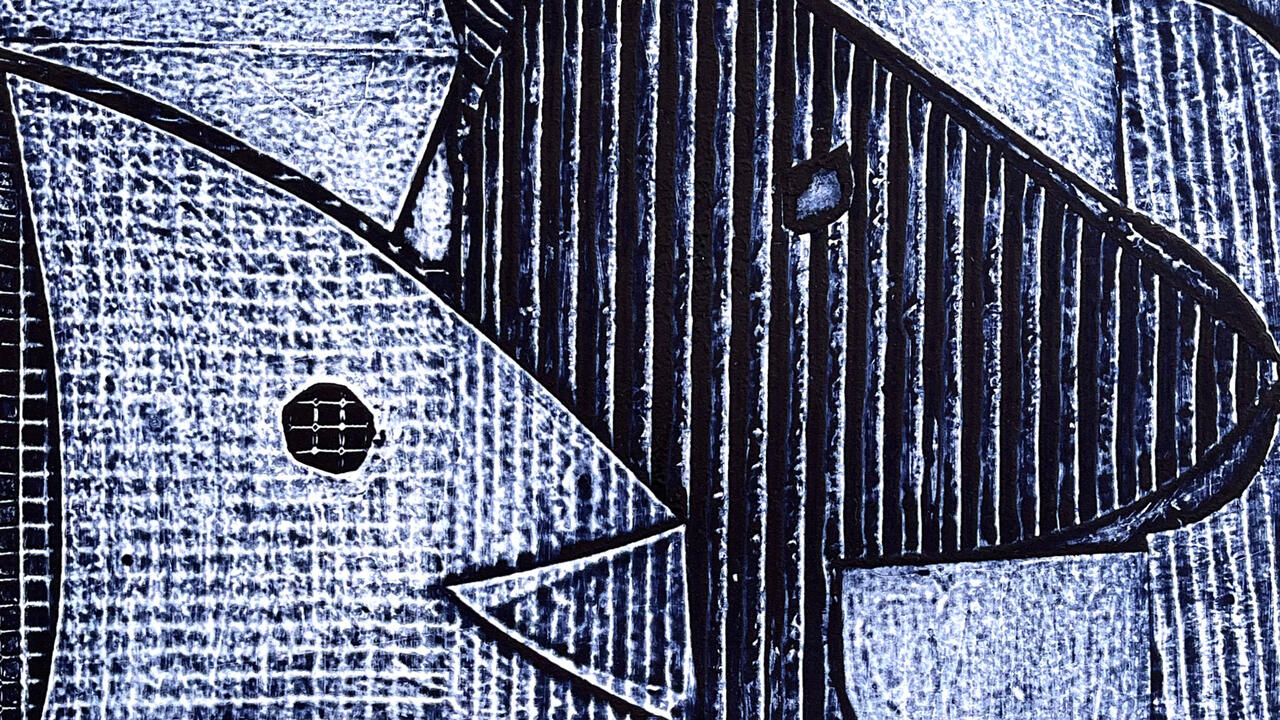

Main image: Lubaina Himid, Swallow Hard: The Lancaster Dinner Service, 2007, paint on porcelain. Courtesy: Hollybush Gardens, London