Looted Art and the ‘Universal Museum’: Can 21st-Century Collections Ever Escape Colonialism’s Violent Legacy?

As the Easter Islanders demand that the British Museum return their statue, it’s time to reconsider the meaning of ‘global artworks’

As the Easter Islanders demand that the British Museum return their statue, it’s time to reconsider the meaning of ‘global artworks’

It is one of the most important of Easter Island’s stone giants, but for 150 years it has stood in the British Museum. If the current governor of the Chilean island, whose indigenous inhabitants are known as the Rapa Nui, has her way, this will change very soon. Last week, a delegation from the island arrived in the United Kingdom and made its way to the British Museum. ‘We are just a body. You, the British people, have our soul’, declared governor Tarita Alarcón Rapu. She herself was seeing the statue for the very first time. Her grandmother, she added tearfully, had always wanted to see the statue but died before she could.

The controversy behind Hoa Hakananai’a, as the statue is called, centres on cultural ownership. Do objects taken from former colonies and other parts of the world belong in the museums of former imperial powers? The answer given by the Rapa Nui is, of course, no. In keeping the statue, the British Museum is holding on to a piece of cultural, historic and spiritual heritage that does not belong to them.

The Easter Islanders aren’t the only ones who feel this way. The week following their plea, two academics – the Senegalese economist and writer Felwine Sarr and French historian Bénédicte Savoy – tasked by the French president Emmanuel Macron to look into the issue of repatriation of cultural heritage, published their report. According to their estimates, 90 percent of African art and antiquities currently reside outside the continent. The study lists the British Museum as containing 69,000 of these works and objects. Many African artworks were taken during the colonial period, between 1885 and 1960, which is itself close to the time (1868) that the statue of Hoa Hakananai’a was carried off by a British naval captain and presented to Queen Victoria, who later gifted it to the British Museum.

‘The Macron Report is generating a thought-provoking debate,’ one British Museum official told France 24, when confronted with Savoy and Sarr’s study, which advocates for the permanent repatriation of artworks taken from Africa. The French, particularly president Macron, who in a speech last year promised a ‘permanent or temporary’ return of African objects would be a ‘priority’ for him, seem to be amenable. Since the publication of Savoy and Sarr’s report, Macron has pledged to return 26 artworks taken from the west African state of Benin ‘without delay’.

The controversy is not entirely new, nor is the intransigence of museums and other institutions to return objects. In 2002, 18 leading museums published a document titled ‘Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums’. In the case of one of its signatories, the British Museum, the document can be read at least partially in response to the Greek government’s claim to the Parthenon marbles held at the museum which continues to define the British Museum’s positioning today. While condemning looting and the illegal trade in antiquities, which must be ‘firmly stopped,’ the document revives the concept of the ‘universal museum,’ describing it as an institution that ‘serves all humanity.’

Repatriation would, argues the document, ‘narrow the focus of museums whose collections are diverse and multifaceted.’ The large museums that currently house art, art objects and antiquities taken from other cultures (which is the focus of repatriation claims) represent, in the view of the document, Enlightenment values such as humanism and internationalism, as opposed to the narrow ‘retentionist’ premises on which the Rapa Nui or the Africans or the Greeks want their objects back. Given the spectacle around the arrival of the Easter Island delegation, officials from the British Museum have now accepted an invitation to visit Easter Island and conduct further talks.

The concept of the ‘universal museum’ bears a similarity to the idea of the ‘global object’, a term that has not specifically been used by the British Museum, but which arguably underpins the arguments in the 2002 ‘Declaration’. In being global objects, items such as the Hoa Hakananai’a, for instance, cannot be thought of as belonging to one country or people. The ‘universal museum,’ on this definition, safeguards these ‘global objects,’ preserving and caring for them and making them available to a global public – who can access them when visiting predominantly Western cities like London and Paris.

No one should believe this. First, as the scholar Bernard Cohn has argued in his book Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge; The British in India (1996), the very transformation of traditional or spiritual or even everyday objects from the colonies into ‘art objects’ for display was a crucial part of the colonial architecture of domination and control. As Cohn writes, the transformation ‘established an enduring structural relationship between India and the West. Europe was progressive, India was static.’ The latter the forever primitive past; the former the evolving future. This second meaning given to objects, available to be gawked at by the British and the French, in turn established the morality of colonial domination. The sheer oddity of a giant head, the sheer lavishness of the Peacock throne, made the moral project of colonialism – the deliverance from barbarity, its imposition of bureaucracy to replace monarchical veneration – crucial and necessary.

Secondly, even if the premises behind the ‘Declaration’ are permitted, the idea of the Museum accepted and the non-proprietorial character of the global object understood, neither is adequate in relation to the problem of who has access to so-called universal museums. The UK Home Office, for instance, was recently accused of refusing visitor visas from applications from African countries, the Indian subcontinent, Cuba, Vietnam, Fiji and Thailand, for apparently inaccurate reasons, with one specialist lawyer calling it a ‘general refusal culture’ which is ‘purely motivated by racism, coupled with a desire to keep numbers low.’

In general, whereas objects from South Asia or Africa are treated with veneration, the people from just those places are discriminated against in their lack of access to the countries holding their cultural history. In this sense, then, the enlightenment project of fostering a ‘common humanity’ via museums (referenced in the 2002 ‘Declaration’) fails on both counts: these museums cannot be accessed by those who shared the objects’s context and genealogical history because they are often not even permitted into the countries where the objects are kept, and these museums fail to educate Westerners as seeing the objects as inherent to the humanity of the artists and craftsmen who made them.

Failing at both of these tasks, the museum, particularly one that makes claims to universality without considering the deceptions behind the claim, confronts the risk of being simply a vestige of dominance and power. To the citizens of former colonies, such displays serve as a reminder of ill-gotten greatness through the laying out of loot and plunder. While the British Empire may have waned long ago, the idea that only the West can properly safeguard and conserve the heritage of the world remains testament to an inherent principle of its moral architecture: the viewers of the ‘global object’ are superior to its makers.

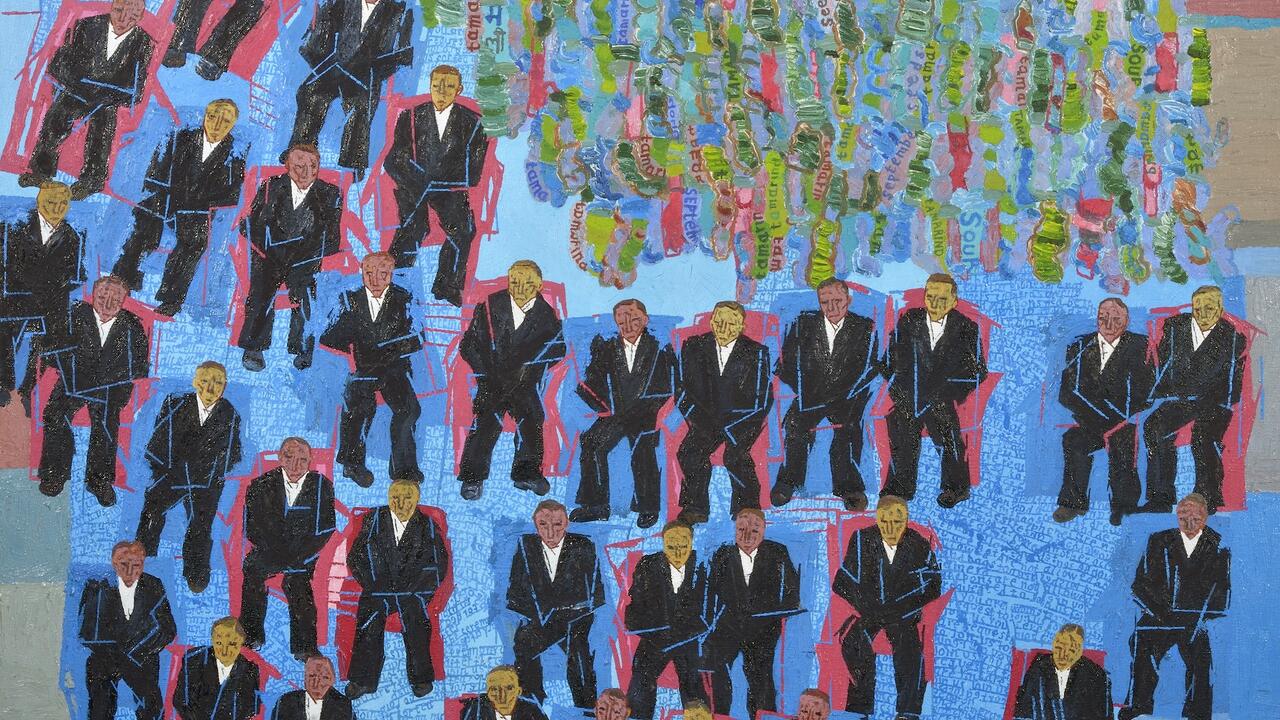

Main image: Easter Island, 2012. Courtesy: Wikimedia Commons; photograph: Lars Juhl Jensen