Lorraine O’Grady is Making Deep Cuts

On the occasion of her retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, the artist speaks to Malik Gaines about her process, politics and vision for a more equitable world

On the occasion of her retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, the artist speaks to Malik Gaines about her process, politics and vision for a more equitable world

Malik Gaines I’ve just finished reading your latest book, Writing in Space, 1973–2019, which was published last September.

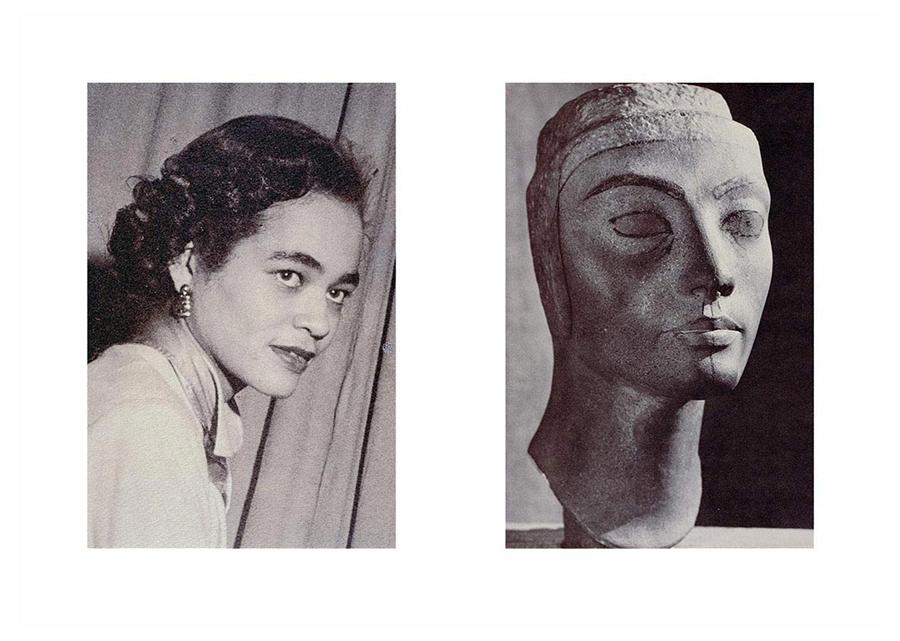

Lorraine O’Grady Everything in the book reinforces the idea that I have been talking about the same things for 40 years, but nobody was listening before. I’m only just now able to get across my anti-binarist critique. Nearly since I started making art, I’ve been making diptychs rather self-consciously as an argument against Western binarism. While speaking with Catherine Morris, the curator of my retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, I slipped in this idea that my work is about ‘Both/And’, which she suggested we make the title of the show.

MG Why do you think people are listening now?

LG That’s the question, isn’t it? I think people weren’t really listening to anybody, not just me. In the art world, people of colour who write are not looked up to or we’re not looked for. They think they can still manage everything so that they don’t have to change anything. When people tell me, ‘Your work is so fresh, it could’ve been made yesterday,’ that’s a sure sign nothing has changed.

MG By ‘they’, I assume you mean the powers that be in white institutions.

LG There’s no question that museums are run for the trustees: they call the shots. This guarantees that the focus falls on the collections rather than on the progress of culture. In order for museums to be really meaningful, they would have to truly give up the privileging of art for the market and exhibit art for change.

MG Was that why you started making art, to create change?

LG I actually started with the worst role models in the world: the surrealists, the dadaists and the futurists. They believed they could incite change, even if that change wasn’t always good. But, for about five years, I didn’t show anybody in the art world my work Art Is … [1983] – in which I mounted an empty gold frame on a float in Harlem’s African American Day Parade, and photographed people in the crowd holding frames around themselves – because it was all for that moment, for that space.

MG Did you think it wouldn’t be taken seriously as art because it was a community-oriented social performance project?

LG Yes. You have to understand that my performance Mlle Bourgeoise Noire [1980–83] predated the work of the Guerrilla Girls by five years. At the time, it was a total non-sequitur to ask a question like: ‘How many Black people are in this gallery?’ The racism and cultural self-satisfaction were appalling. The only Black artists at that time who could even be considered artists by the structure in place were using white aesthetics. Somebody like Faith Ringgold was just laughed at.

MG But now, even those works are acquiring new value in this trustee-led structure.

LG Yes. The biggest change I’ve seen is that it’s now possible to use non-European aesthetics to make a point and for that point more or less to be understood.

MG It doesn’t help that younger people, especially on social media, don’t feel the need to make sense of things inside a modernist, avant-gardist lineage. Whereas that used to be the entire explanation for the work. Mlle Bourgeoise Noire entered that fraught, modernist space in a contestatory way. Your work has the bravery to take up its own intellectual space and then demand to be accepted on its own terms.

LG I certainly thought: if not me, then who? I felt that I could speak the language.

I don’t think anybody could be more aware than I am that this is not a ‘Both/And’ moment. We’re living through a time in which things are more divided than they’ve ever been. When I was planning this retrospective, I thought I might end up having to defend my belief that everybody is equally being done an injustice by the Western system of thought.

MG Do you mean that your critique of Western thought and the way it shows up in art is a critique that doesn’t only serve Black people, but everyone?

LG There’s nothing wrong with difference: the problem lies in the hierarchization of difference. I mean to dislodge our positioning at the bottom of every hierarchy. This retrospective was really odd for me because, everywhere I turned, there were requests to provide inspiration and opportunities for joy.

MG I can imagine how someone could turn your biography into a narrative of redemption: that of a trailblazer who persevered against all racist odds.

LG I simply define joy differently. Ta-Nehisi Coates says he’s to the left of the Afro-pessimist; I’m to the left of Coates. I really liked the title of his book The Beautiful Struggle (2008); the struggle itself is the source of joy.

MG The struggle is alive.

LG Yes, and it’s not going anywhere. It’s been said that when bad things happen to Black folks, good things happen to Black artists. I think we, as a people, are in very bad shape. I’m almost 90 and, in my lifetime, the only employer that has provided an underpinning for the Black middle class is the government. So, any time you hear anybody say they want to reduce the size of government, that only has one result, and it’s not good for Black folks. The destruction of real-estate values and land ownership – every index you can think of that would measure the stability of a middle class – is being decimated, even as we sit here.

Of course, the Black Lives Matter movement gives me hope. They’re the ones that get the most publicity, but there are other organizations doing incredible work, like the Movement for Black Lives and Color of Change, inspired by the work of the academy.

MG Writing has always been a central part of – as well as a way to contextualize – your work. Your ground-breaking essay ‘Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity’ (1992), for instance, has circulated very widely. You were also a music journalist for years. How do you see writing as part of your artistic practice?

LG Writing and art are just two different forms of thinking.

MG Has writing always been central to the way you organize your thinking?

LG In Writing in Space, there’s a little story about my first novel, which I wrote when I was in the second or third grade. I showed it to my schoolmates and a couple of them disagreed with the way they were portrayed, and there was a fight. It was one of those knockdown, drag-out fights. I had long nails and this other girl ended up with a gash. Her mother took her to the police station and I ended up in juvenile court. I got a horrible lecture from this guy who didn’t see an eight year old writing a novel; he saw a little savage.

MG You went in a novelist and you came out a violent criminal!

LG Exactly. On the way home, my mother said: ‘If I ever catch you writing another word …’ It took me exactly 20 years to get back into it. I was 28 when I went to the Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

MG Growing up in Boston, did you live in a Jamaican community?

LG Yes. There were not that many West Indians and they all knew each other. As a result, during the entire course of my childhood, I don’t think I ever saw anybody come into my home as a guest who was not West Indian. That’s pretty closed. I think that was part of the reason why African Americans really looked down on us at the time.

When they came here, my parents had so much baggage from the West Indies. The only person I’ve ever heard speak publicly about that is the cultural theorist Stuart Hall. He grew up in Jamaica and moved to the UK to attend university, but we had very similar experiences. He always said his mother hated it when he did anything other than praise ‘jolly England’ and try to fit in at Oxford. For me, the hardest part was lacking the language to describe myself. That language didn’t even enter common discourse until the early 1990s, with words like ‘diaspora’.

MG Art Is … was adapted last year by the Biden-Harris presidential election campaign. How did that come together?

LG The deputy director of Joe Biden’s campaign and Kamala Harris’s video director had both separately seen Art Is … as part of the touring exhibition ‘Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power’ at the Broad Museum in Los Angeles, and it brought them to tears. They had not seen Black people just being themselves in art. The experience made them change the way they were approaching their ad campaign: they decided its underlying thrust would not be to answer the arguments of the opposition, but simply to present their own vision of what they would want life to be like under a Biden administration. They expanded the scope of the original project from four videographers to 30, who filmed people all around the country in their own landscapes. They put more money into that video than into anything else they did for the campaign, which was a gamble because it was only to be shown if Biden won. It premiered the day he was declared the winner. I truly can say that they took my idea further than I could ever have imagined.

MG Perhaps people wanted you to make your retrospective into an inspirational story because there is that quality to your work, especially in a piece like Art Is …, which engages directly with the community.

LG The fact that I didn’t give up is the only thing I can give myself credit for. Like that gospel song ‘Lord, I’ve Had My Day’, which Marion Williams recorded in 1964, none of this would’ve been possible if I hadn’t already had my day. I was able to concentrate on making art because I’d done everything else that I wanted to do: I’d travelled, lived abroad, had boyfriends who were good in bed and explored myself. That can give you, if not confidence, at least freedom to do what you have to do. If I had just been smart, I don’t know that I would’ve had the confidence. I was pretty, too. That was part of my problem: I was too cute for too long. I got much more attention from the outside world for my looks than I ever got for my brains. I always knew that I could do anything I wanted to do. It’s unrealistic to have that kind of hubris; I gave up every job I had as soon as I figured out how to do it well. But the one thing that I have never gotten bored with, not for one minute, is making art, because I can’t do it that well. I have to really work hard. The challenge of it keeps me interested.

MG Do you feel like you want to shift gears after the retrospective?

LG I’m actually planning to write another book; I’ve written a bunch of stuff since it was published. One of the best and most autobiographical things I’ve written is ‘Notes on a Translated Life’ (2020), which was originally a catalogue essay for the ‘Boston’s Apollo’ exhibition at the city’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, then later republished by Hyperallergic. The show’s curator, Nathaniel Silver, found a cache of photographs in a drawer of John Singer Sargent making images of this Black model named Thomas McKeller, who he had met just before he was about to start work on the rotunda murals at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Sargent was staying at the Vendome hotel, and this young man was operating the elevator. McKeller was gay and Sargent was closeted. Sargent made him the subject of every single figure in the murals, both male and female.

So, I started to write an essay about my father, who was about six years younger than McKeller. They had probably met each other, or at least tipped the hat. I was able to compare what it must have been like to be a young Black gay man translating himself from North Carolina to Boston, and a guy who translated himself from Kingston to Boston. It would have been the first time they’d seen so many white people, the first time they’d been so cold, the first time they’d been so locked in and given absolutely no opportunities.

In February last year, when I was invited to give a talk at Smith College, I found new language to describe what I do. I explained that I’m not a depth artist: I don’t take one thing and then go down through layers and layers until I reach some bedrock truth; I don’t have the skillset for that. I am a breadth artist: I make incisions into the skin of culture and then stuff as much of myself into each little incision that I make, so that nobody could ever think I only do one kind of thing, or that I am only one kind of person.

MG For me, ‘Both/And’ fits both the diptychs and your performance interventions. Both writing and formal artwork. Both being a Black person and being a person of colour. Both smart and cute.

LG Yes. I want people to know that Black people can be complicated. That has always been my goal.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 218 with the headline ‘Interview:Lorraine O'Grady'

Main image: Lorraine O’Grady, 2018. All images courtesy: © Lorraine O’Grady, Alexander Gray Associates, New York, ARS, New York, and DACS, London; photograph: Ross Collab