Lou Lou Sainsbury Dreams of A More Liberated Future

At Gasworks, London, the artist explores the possibilities that come with rejecting forms imposed by outsiders and creating our own

At Gasworks, London, the artist explores the possibilities that come with rejecting forms imposed by outsiders and creating our own

In Lou Lou Sainsbury’s descending notes (2022) – the centrepiece of her solo exhibition, ‘Earth Is a Deadname’, at London’s Gasworks – one of the performers tells the audience that ‘the words don’t form don’t stop forming’. This dissonant approach to language characterizes both the film and The Law of Desire Is Fascist (2022), a poem written by Sainsbury and artist Kari Leigh Rosenfeld, and recorded by queer poet Jo Mariner as a sound work. The word ‘form’ is crucial: this work is, at least partly, about how words form us, as trans people whose identities were formed largely by the categorizations of the 20th century medical establishment, but mainly about the aesthetic, social and political possibilities that come with rejecting the forms imposed by outsiders and creating our own.

Gasworks’s documentation explains that Sainsbury ‘identifies as a time traveller’, détourning the idiotic joke made by boring reactionary comedians about ‘identifying as an attack helicopter’ to ask: why shouldn’t we weave these speculative possibilities not just into our work, but into our senses of self? Parts of ‘Earth Is a Deadname’ dream of a more liberated future, most obviously in descending notes, where a sample from Donny Hathaway’s ‘A Song for You’ (1971) says to someone unspecified: ‘I love you in a place where there’s no space and time.’ Cosmic imagery runs through the exhibition (which takes its title from a line in The Law of Desire Is Fascist) from this narrator’s speculation that she might be ‘more fuckable […] in a molecular vacuum’ in the silver, retro-futurist lettering in which fragments of poetry are rendered on the walls.

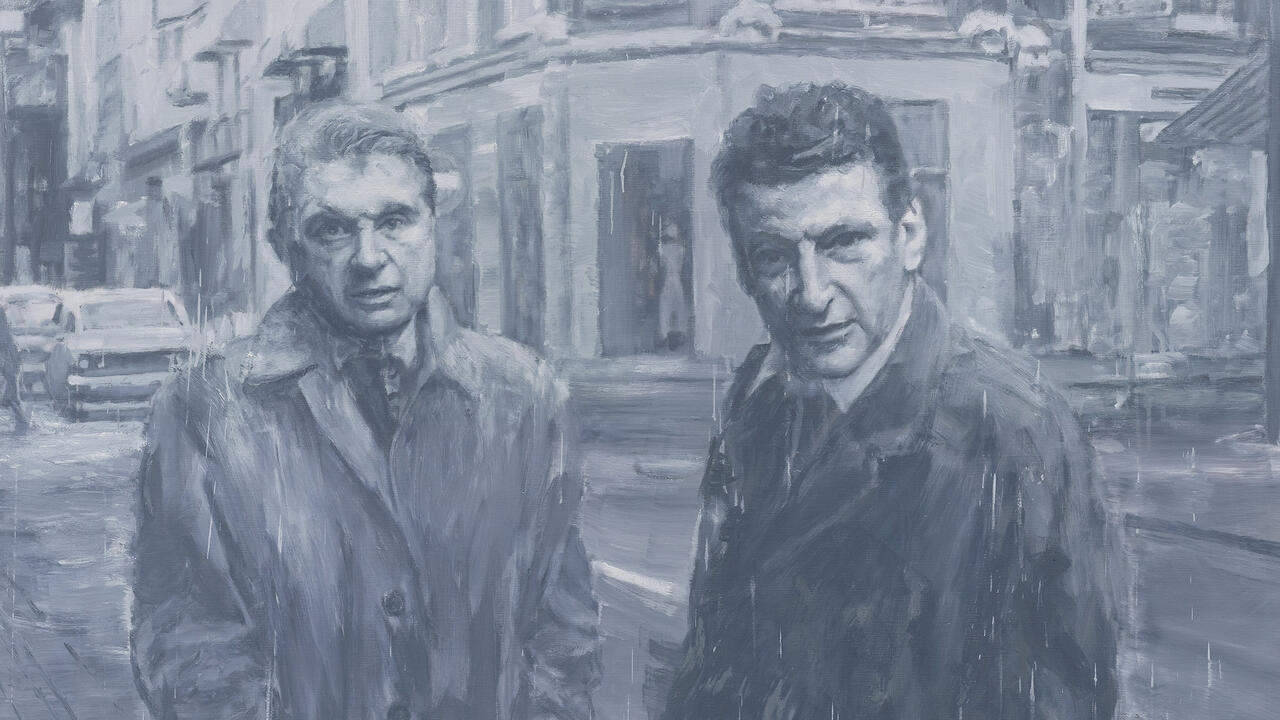

Other parts deal with the quotidian difficulties of trans living, notably in Rosenfeld’s portrait of Sainsbury with a line of oestrogen gel on her arm. In the slow and subtly sad descending notes, the characters’ close attention to each other (particularly to the way they breathe) feels like an attempt to find sanctuary in a world becoming ever-more hostile to gender non-conforming people. In the knowledge that outsiders are unlikely to meaningfully support them in the face of a legislative and media onslaught – realities the film keeps firmly in the subtext – this care is essential for survival. The intensely private nature of their interactions, mostly confined to one room, contrasts markedly with The Law of Desire Is Fascist’s dreams of no longer being ‘trapped in a body’.

![Lou Lou Sainsbury, [Nov 30, 2021 at 6:12:27 PM]: just a quick one. whats ya date of birth? im putting u as a witness for my trans form, 2022. Portrait of Lou Lou Sainsbury by Kari Rosenfeld, C-print. Commissioned and produced by Gasworks. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate](https://static.frieze.com/files/inline-images/01-lou-lou-sainsbury-2022-gasworks.jpg)

While much of the rest of the installation feels like it’s supporting the sound and moving-image works, there are two obvious highlights. The first is the large, stained-glass sculpture Do you think the dead come back and watch the living? (2022), which incorporates dried flowers and honey into its steel frame. Its translucency references a line in Torrey Peters’s Detransition, Baby (2021) about how ‘a trans woman’s deepest desire […] is actually to stand in good lighting’, the matte colours of its circles striking the viewer first, suggesting that many trans people in the current climate would prefer not to stand out. The second is the empty wooden cabinet marked ‘to the pain in the womb’, on top of which sit personal gifts, souvenirs and used wrappers from hormone therapy, reinforcing the focus on friendship, love and care in descending notes. The art world has talked so much of care amidst the austerity and political ruptures that followed the 2008 financial crisis: for Sainsbury, this is not just empty rhetoric, nor an end in itself, but the basis for a transformed society, with things as they are and things as they could be in constant, fascinating tension.

Lou Lou Sainsbury’s ‘Earth Is a Deadname’ is at Gasworks, London, UK, until 18 September.

Main image: Lou Lou Sainsbury, ‘Earth is a Deadname’, 2022, exhibition view. Courtesy: the artist and Gasworks, London; photograph: Andy Keate