Manfred Kuttner

Johann König, Berlin, Germany

Johann König, Berlin, Germany

Manfred Kuttner’s history has something fable-like about it: in the early 1960s in Dusseldorf, he and three other young artists – Gerhard Richter, Sigmar Polke and Konrad Lueg (later known as Konrad Fischer) – form a group and show together several times. But by the end of 1964, Kuttner was sidelined; his more abstract approach no longer fits with the ‘New Realist’ work of the other three. With a wife and small children to support, he gives up art in favour of an advertising job and a stable wage. After his final exhibition in Rene Block’s Berlin gallery in 1965, his paintings languish in the cellar of his house in the Rhineland.

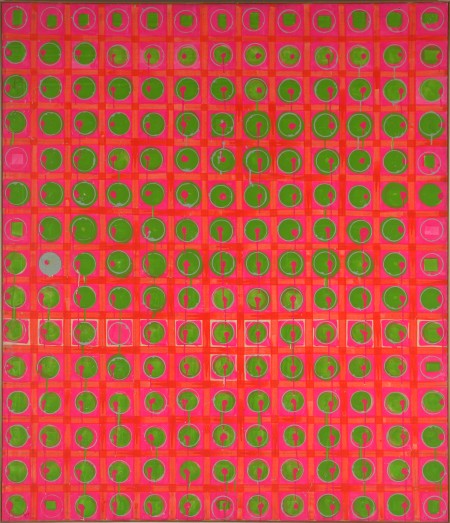

It is almost impossible to view Kuttner’s works, pulled out and dusted off (and in some cases restored) 40 years later, outside of this prism of mythologizing history. They have a kind of instant credibility given his close association with Richter, Polke and Lueg. But there is something about their slapdash Op-art effects and embrace of feverish neon colours that renders them still startling. The eight neon abstract paintings exhibited here share some of the systematic patterning of Victor Vasarely or Bridget Riley, but they have none of the taut perfectionism on which his Op art contemporaries depended for their hallucinatory effects. A kind of handmade carelessness and experimental air frees them from illusionism to investigative instead approaches to process and materials.

In Achterbahn (Roller Coaster, 1964), for instance, rows of blue circles line up against a red background; in each circle is a pink square, centrally placed, in some rows upright, in others turning, rolling over. The effect is giddying: the circles seem to jiggle in various directions, like rows of cogs or the rattling wheels of roller coaster coaches. Attempts to trace any coherent system, however, are foiled by blue drips that trespass onto the pink squares, or uneven white gaps around them, while areas that should surely be red are left untouched. Although close up it bears a certain similarity to a child’s potato-print painting, its thrilling and unexpected vibrancy when seen from a short distance clarifies why his work was initially christened ‘kinetic’ art. Another painting Tombola (1962) racks up a barrage of patterning in complementary colours to similar dizzying effect, the breaks in its pattern alluding to the slippages, coincidences, juxtapositions and velocity of daily life. Attempts at ordering seem forever skewered by the introduction of another experiment, an accident, a ‘what if’.

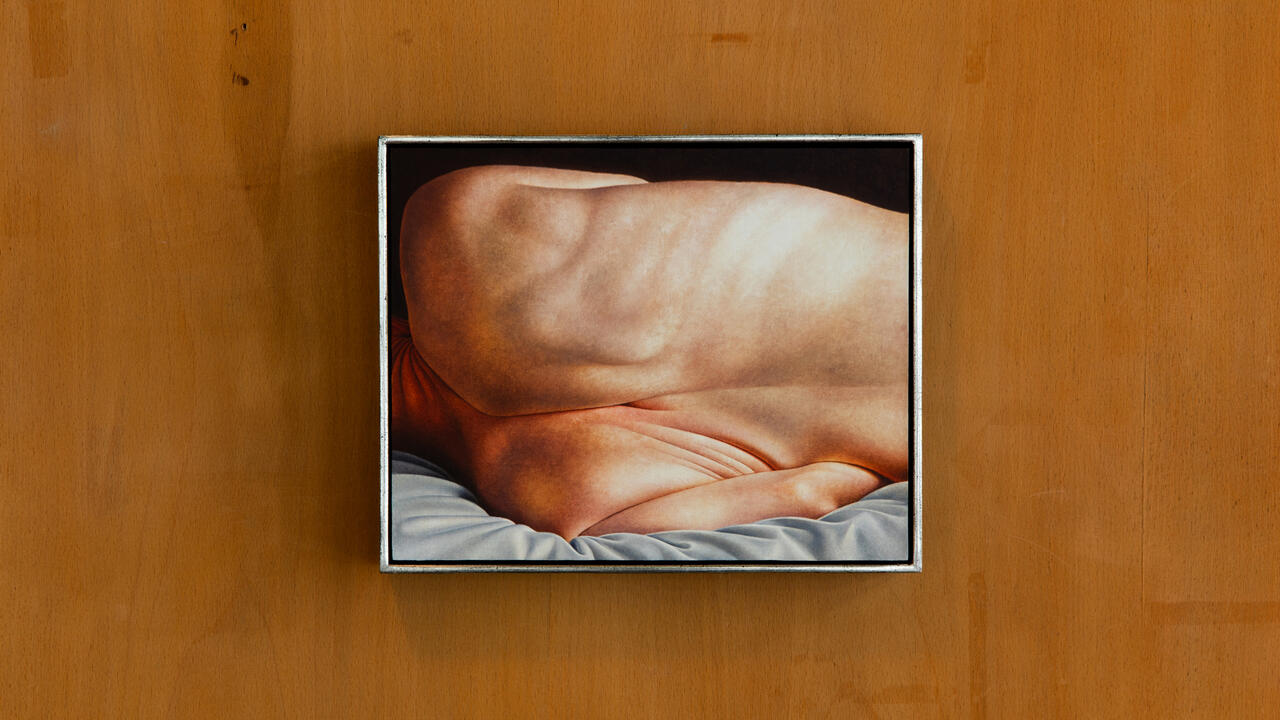

This relation of abstraction’s attempt at ordering to reality’s confusion was spelt out more clearly in a selection of Kuttner’s ink on paper drawings from 1962. Matratze (Mattress) is a linear arrangement of diagonal lozenges, looping script and circles that loosely represent the springs of a mattress. An 8mm film (A–Z, 1963) develops this abstractionist take on reality further: a fast edit of still shots pictures the journey from his apartment through the streets of Dusseldorf to his studio, focusing on crowds of people, shop windows, signage. Intermittently, hand coloured frames blinking red or yellow appear, introducing a hallucinogenic atmosphere into the relentless flow and thrum of the everyday. Also included in the exhibition were three earlier, transitional works: canvases whose dense grey surfaces of layered patterning have little to distinguish them. The discovery and interest in the material qualities of a newly patented fluorescent paint was clearly a turning point for Kuttner, spawning not only the vibrant paintings here but also several dada-esque objects such as a chair coated in fluorescent pink and balanced on four metal pins so that, initially, it seems to hover slightly (Heiliger Stuhl, Holy Chair, 1962/2006).

The real strength of Kuttner’s work, however, lies in his abstract paintings, which share qualities with those of many younger contemporary artists; Thomas Scheibitz and Anselm Reyle are obvious examples (Kuttner’s work was shown with theirs at Tate Modern in 2007). Reyle in particular shares a concern with the alienating properties of fluorescent paint and a fascination with the effect of drips or paint-can imprints on geometric abstraction. But artists such as Udomsak Krisanamis also spring to mind, whose process of abstraction is all-encompassing, absorbing whatever is around it, while remaining free to daydream or peter out.

Kuttner had just three productive years as an artist before he gave up at the age of 28. This is a very limited field to mine, and it is hard not to conjecture where his work might have gone had he continued, particularly since he died last year at the age of 70. But it is nonetheless instructive and rewarding to have the opportunity of seeing these long-hidden alternatives to the New Realism or Op art perfectionism of Kuttner’s generation.