Mary Ramsden

Though supposedly ‘smart’ and sleek, today’s mobile phones cause many of us to make a mess. We leave sticky finger prints on their surfaces – shiny slicks of grease swiped across screens. Perhaps these actions unwittingly turn us all into painters, repeatedly making our mark, gesturing upon planes to leave traces of thought and movement.

‘Swipe’ was British artist Mary Ramsden’s second solo show with Pilar Corrias – the first was in 2012 while she was still in her final year at the Royal Academy School. It comprised 13 small-scale paintings that traverse the digital and material worlds to ultimately place importance on the physical object and its sensible presence. In an age in which digital platforms proliferate, disseminating intangible whirls of words and images for inexhaustible consumption, what role – or relevance – does painting have in expressing today’s (im)material world? Indeed, do we still live in a material world – am I still a material girl?

In a recent interview about art and the digital, the artist asked: ‘How do you make something stick these days? How do you make something sit differently?’ Primarily abstract, layering quadrilaterals at subtly shifting angles, her paintings investigate how space is perceived now that computer screens provide constructed environments that can seduce us in equal measure to the physical spaces surrounding us. The digital realm is characterized by its flatness, by surface: cropped layers of content and overlapping windows compressing three-dimensionality.

While Ramsden’s works are rooted in the traditional painting vocabulary of oil on board, her surfaces are somewhat more experimental. In Lick 4 (2014) a pearlescent plane of white gently shimmers, blemished by a succulent smear of blue and green, as though a lollipop-stained tongue or blackberry-dyed finger had been run across it. In another work, Lurid and Cute (2015), a matt black monochrome surrenders a little streak of blue, almost liquid in its flow, within which there are subtle smudges of purple and pink. There is a sumptuousness to these works that turns utilitarian swipes across electronic touchscreens into movements that are meaningful and meditative.

Particularly successful was Zerstörung (Destruction, 2015) a two-panel work that suggests obliteration through covering up and adding, rather than demolishing. Geometric layers of white paint are built up and overlain, like sheets of paper, to block out a background surface that has been scratched, crisscrossed and smudged by finger-marks in coral pink and cobalt blue. The painting’s luminous yellow edges hum and shimmer off the surrounding white wall, as if this were an electronic surface never at rest, constantly changing and shifting.

Paintings such as Sunroof (2015) felt less compelling, layering large white voids upon black backgrounds in which only hints of the artist’s hand are discernible. Often, the edges of Ramsden’s paintings are of particular importance; swathes of paint amass, sometimes dappled and flicked, or thickly layered like icing at the edge of a cake. It is at these edges that information from the buried surfaces beneath bleeds through – as if we were able to access the search history of the work.

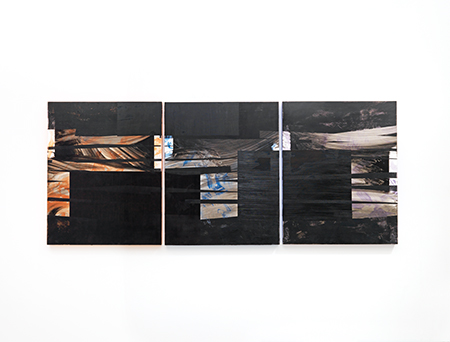

A highlight was Hold Still (2015), a triptych of orange, blue and purple panels in which a swiping motion was almost palpable in the slide of coloured brushstrokes layered beneath black and white squares – as if mimicking the warmth of human touch or light against cold machine. Its playful title recalls hands that won’t rest, constantly fidgeting with the technology at our fingertips. Indeed, many of Ramsden’s titles – … all milkshake and ice-cream or … this television is just a large, broken radio with abstract art on the front – suggest the frenetic and spontaneous modes of personal expression of social-networking sites such as Twitter. Ramsden brings us back from these virtual spaces of connectivity to the human touch of painterly gestures and handled materials.