Masahisa Fukase

Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, UK

Michael Hoppen Gallery, London, UK

‘The Solitude of Ravens’, by the late Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase, is an expressive metaphor of almost unmitigated darkness. Shot between 1975 and 1982, ‘Ravens’ stands as a requiem for Fukase’s marriage to Yo¯ko Wanibe. It is bookended by his two other most significant projects, both of which are also currently on show in London (as part of the group exhibition ‘Performing for the Camera’ at Tate Modern). ‘From Window’ (1974), a series of ‘straight’ photographs of Wanibe, speaks eloquently of the highs and lows of their marriage and its break-up. By contrast, 1991’s ‘Bukubuku’ (Bubbling) is a heavily claustrophobic, often surreal, set of self-portraits, which Fukase made in the bath after learning his ex-wife was to remarry. While all three bodies of work successfully convey Fukase’s feelings towards Wanibe, it is ‘Ravens’, on display at Michael Hoppen Gallery, which is his masterpiece.

The raven is thought to bode ill in many cultures, including Japan’s. In Fukase’s consummate photographic allegory, huge conspiracies of ravens rise from the gloom as if to augur the end of the world. Dark murders of crows sit in dark trees, their evil eyes lit up. The sinister tone is unrelenting, and the uneasy sense that the pictures are about something they don’t show is maintained throughout. Many a male artist the world over has photographed his wife – from Harry Callahan to Nobuyoshi Araki – but none has done so with such dark intensity without her actually appearing in the photographs.

‘Ravens’ skillfully emphasizes feeling over formality, and blur and grain predominate. This loose approach has an illustrious heritage in Japanese photography. (Daido Moriyama’s 1972 book Bye Bye Photography is one extreme example.) Many of the best photographers produce strong work in one signature style but, in ‘Ravens’, Fukase mixes different approaches – such as a freeze-frame close up of a crow’s feet in flight or a conventional shot of a sour-faced flesh-eating cat – with equal dexterity. Furthermore, while many great photographers have not been the best printers of their own work, all 32 vintage black and white photographs displayed here were masterfully printed by Fukase himself.

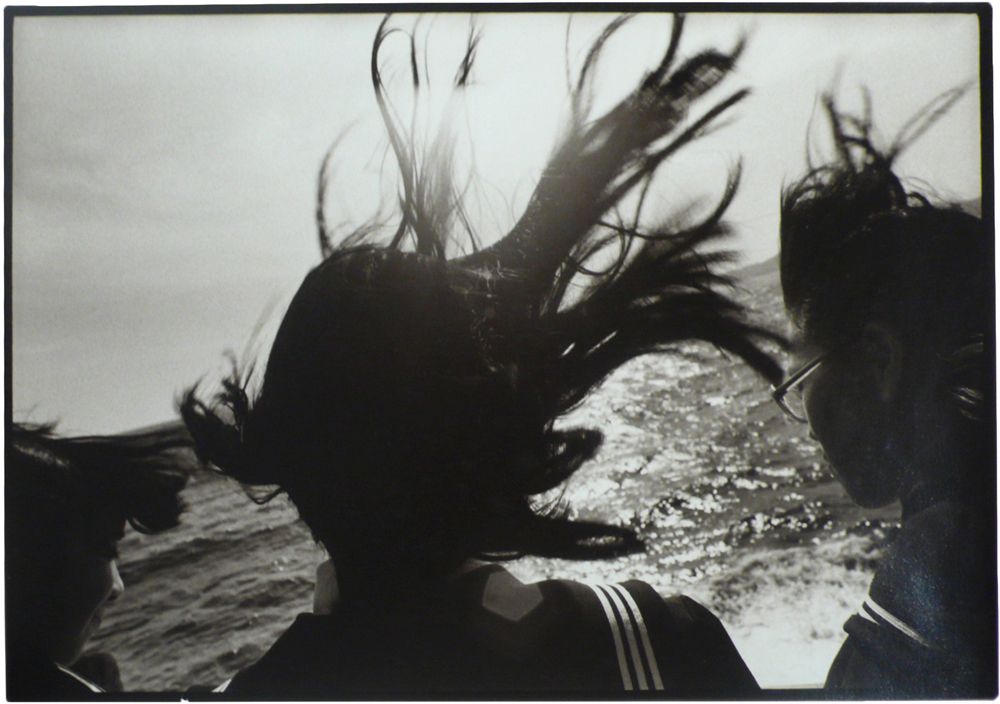

The exhibition isn’t flawless: its layout, with the first few images in a corridor before you enter the main room, is disjointed; and three razor-sharp silhouettes of birds on wires jar with the otherwise lyrical tone. But these are minor quibbles. Photography series often contain a significant minority of weaker images to support an overall narrative, but here almost any one of the 32 individual works could stand alone as a beautifully executed metaphor to lost love. In one oppressive picture, a hulking great ‘metal bird’ (a bomber aircraft?) weighs as heavily on the viewer as it does in Japanese history. In another, an enormous black cloud sits over a forbidding landscape like a permanent depression, as crushing a photograph of despair as any ever made. On the opposite wall, the exhibition’s one moment of relief is truly euphoric: a young woman’s long hair, black as a raven, flies free against an elemental backdrop of wind, water and sun. But, even here, the tilted horizon hints that all is not well. The omnivorous crow soon returns and, in the last grainy photograph, its all-consuming blackness swallows everything. In retrospect, this final image stands as the darkest of portents: in 1992, Fukase fell down some stairs and into a coma, in which he remained for 20 years until his death. Wanibe visited him frequently throughout.