Meiro Koizumi: Can VR Force Us to Watch When We’d Rather Look Away?

At Mujin-to Production, Tokyo, the artist’s Clockwork Orange-like experiments confront us with the visceral traumas of war

At Mujin-to Production, Tokyo, the artist’s Clockwork Orange-like experiments confront us with the visceral traumas of war

On Saturday, I am with my girlfriend and her young sons shopping for household goods at a Target in North Carolina. Later, at the airport, I hear the news that a young man has killed 22 people with an adapted AK-47 in a Walmart in El Paso. It is a hate crime aimed at ‘Mexican’ immigrants. On Tuesday, I am sitting in Mujin-to Production’s new space in Tokyo, watching two video works by Meiro Koizumi about memory and trauma as a result of the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, grouped under the aggro-surreal title ‘Dreamscapegoatfuck’. One, Battlelands (2018), is set in Miami and, judging from their accents, most of the subjects are Latino. Gun-based terrorism in America is not broached in either movie, but nor is it a perspective I simply brought with me through customs.

Originally commissioned by the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, the 56-minute, double-screen video Battlelands features seven US military veterans of recent wars in the Middle East. Aside from one shot that shows viewers the set-up, we never see their faces. After being blindfolded, bodycams are mounted on their heads. Standing in the street, in a park, on the waterfront or (most often) in their homes, they first briefly describe the familiar scene before them: ‘This is my living room’; ‘This is a little table where the kids draw and read books’; ‘We are in downtown Miami’ etc. Then, in the same places, they are asked to narrate the time they felt most under duress on the battlefield. Dead bodies, bullets whizzing overhead, unknown trucks fast approaching and, in multiple cases, children looking on, wielding rocks, throwing them. ‘I can’t shoot them because they’re kids,’ one guy explains, his voice quivering. While blindness facilitates psychic travel and traumatic recall for the veterans, for the viewer, who hears war while seeing ‘home’, the US unfolds as a virtual battlefield, a landscape of potential threats and imminent firefights. Koizumi makes this connection explicit later on with footage of a shooter game set on the streets of America and a sequence in which one veteran’s panicked narration is juxtaposed with images and audio of children on a playground and the explosions of a fireworks display. Elsewhere in the gallery, multiple white plaster casts of a boy’s head, leg and arm parts (modelled on the artist’s own son) are ritualistically arranged in a starburst-shaped pile.

Sacrifice (2018), made me ill. Here the viewer is blinded to his or her immediate surroundings. You sit, don VR headgear and find yourself on the streets of Baghdad being introduced to an out-of-shot Ahmad, whose family was killed in a US helicopter attack when he was just 13. Next you are in someone’s home, where you see Ahmad, now a young man, standing before a mirror being equipped with a 3D VR camera. You are in Ahmad’s body. Sitting in a living room furnished with nothing but chairs and family portraits, you hear him recount that tragic day. The video then cuts to Ahmad’s face – his nose but an inch away, his lashes and beard hairs singly visible – as a computer voice translates Ahmad’s recollections in greater detail. The proximity is uncomfortable, but there’s no backing away since the mask, and thus Ahmad, follows your head wherever you move it. Though departing from a similar first-person perspective to Battlelands, Sacrifice induces an even greater state of empathy by embedding the viewer virtually in the subject’s body. Made nauseous through the effects of VR, then forced to confront another in pain with no recourse to escape, we find ourselves strapped into what feels like some experimental, Clockwork Orange-like model of ‘corrective’ viewership.

‘Dreamscapegoatfuck’ was on view at Mujin-to Production, Tokyo, from 20 July until 31 August 2019.

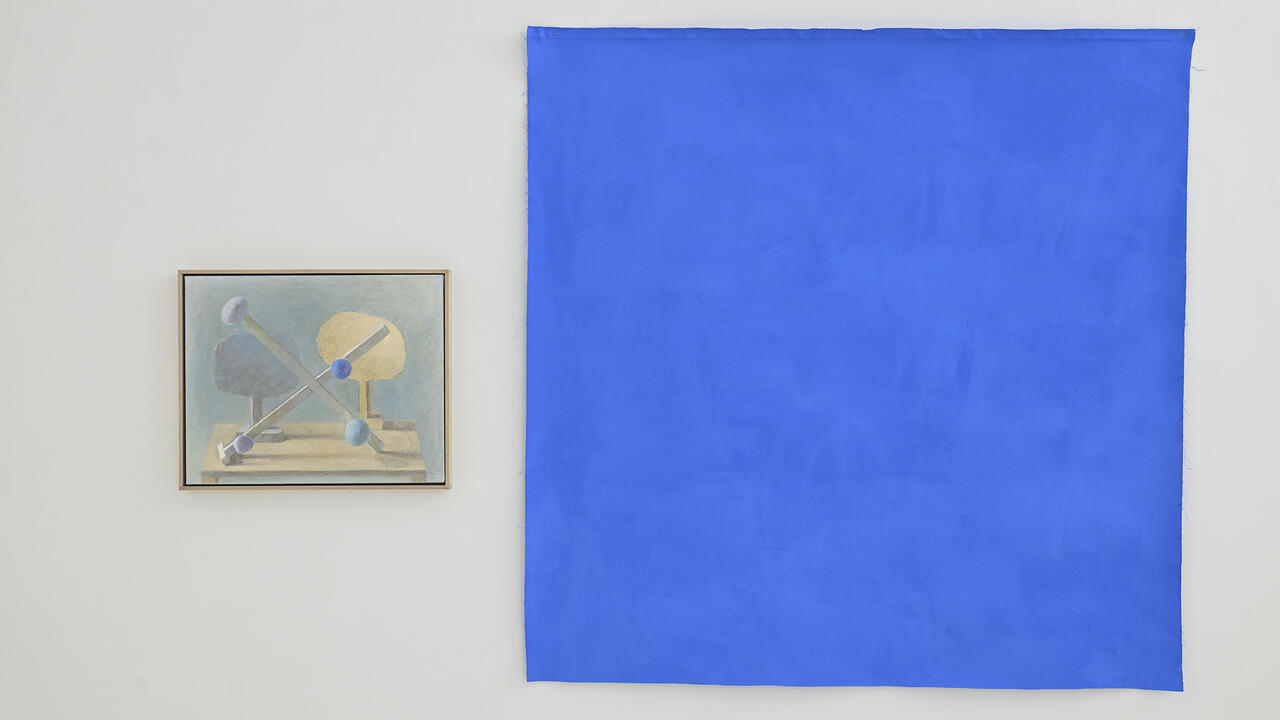

Main image: Meiro Koizumi, ‘Dreamscapegoatfuck’, 2019, installation view, MUJIN-TO Production, Tokyo. Courtesy: the artist and MUJIN-TO Production, Tokyo; photograph: Kenji Morita