Michaela Eichwald's Material Imaginaries

On the occasion of the artist's solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Sarah E. James considers the artist's idiosyncratic abstractions

On the occasion of the artist's solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Sarah E. James considers the artist's idiosyncratic abstractions

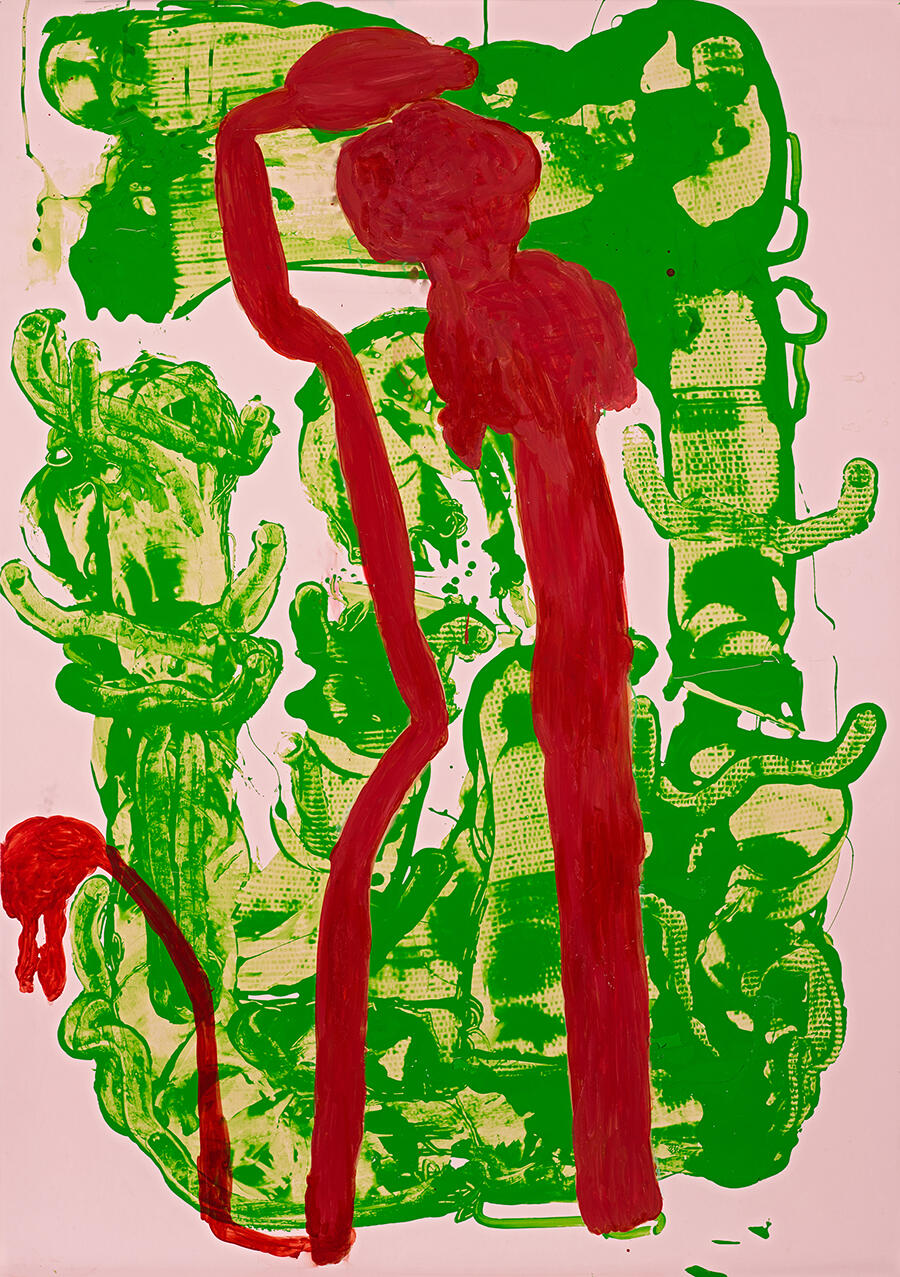

Currently on view at Kunsthalle Basel, Michaela Eichwald’s latest works – a new group of around 20 abstract paintings produced during 2020–21 – are monumental in scale and frequently court the figurative. Their materials are those with which her practice has become synonymous: monochromatic or occasionally patterned PVC polyurethane fabric – repurposed but redolent with its everyday uses: car seats, tight trousers and cheap, high-street fashion – daubed and layered with acrylic, lacquer, spray paint and shellac ink. The pleather she paints on – a trashy slap in the face to traditional canvas – is the painterly equivalent of the expandable foam and resin she uses in the small, sculptural fetish objects she exhibits alongside her paintings. These underscore the intermediality at the heart of her sprawling and inarguably good-looking oeuvre, which niftily colonizes the traditional mediums of art. In this, her practice brings to mind the work of Isa Genzken, an established member of the Cologne art scene when Eichwald was starting out as an artist in the 1980s.

Eichwald works alone without studio assistants, sometimes producing her paintings laid out on the floor or stapled to the wall, imbuing them with traces – shoe prints, finger smears – of their time in her company. Shades of pink, mauve and magenta feature heavily in these recent works, paired with sherbet yellows, mustards, reds and browns. In several, the natural world provides her loose subject matter, deliberately parleying with the synthetic fabrics their organic forms dance on. In Panzerwiese Hartelholz (2020) – first shown in December last year at Eichwald’s solo exhibition at Lenbachhaus Munich – a landscape bristling against a vermillion backdrop sees giant hands, feet and other bodily and biomorphic forms imprinted in white, saluting and treading their way alongside abstract, petrol-blue forms – suggestive of fauna, branches and winding pathways – produced by the twisting hand dispensing spray paint from a can. In others, such as the vast, portrait-format Freies Erzittern in sich selbst (Free Trembling within Yourself, 2020), which stretches almost three metres high, Eichwald turns inwards to play with the materiality of abstract thoughts. Primrose yellow, brown and grey are plastered over the still-visible pimpled texture of the patterned leatherette ground. As with many of her new works, these paintings seem to riff on and reinvent early colour field abstraction, in particular Mark Rothko’s ‘Multiform’ works of the late 1940s, such as No. 18 (1946).

Eichwald often works with non-artistic painterly substitutes such as wood stain, stickers and metallic marker pen. In Durchseelung der Arbeit (Soaking Work, 2020) – lurid green pleather featuring biomorphic shapes that suggest forms from cartoon characters to human organs – she uses fake blood instead of red paint. It’s hard not to wonder whether this material was chosen for the chuckle it elicits in

the list of media. Eichwald’s appropriation of anti-artistic materials and her use of mass-produced fabrics pay tribute to Sigmar Polke – another big name in the Cologne art scene of the 1980s. She nods to her self-conscious appropriation of these local styles and scenes in the titling of a pink and chocolate-brown shellac and lacquered work, Kölner Morphologie (Cologne Morphology, 2020).

An olive-green painting from 2018, titled Hierophant, depicts the symbolic titular figure – a revealer of sacred things and an embodiment of cultural tradition and moral or religious teachings, as well as a popular tarot card representing a period of conforming to convention or tradition. The artist’s recent works include similar symbolic appropriations. In Heilige Madonna ohne Kind mit Spenderehepaar (Holy Madonna without Child with Donor Couple, 2020), for instance, the Virgin Mary is reimagined in the age of IVF and surrogacy.

It isn’t surprising that so many art-historical reinventions underscore Eichwald’s paintings given that she studied art history, philosophy and literature at university rather than fine art. Her preference for situating her practice outside of the traditional institutions of art is underscored by her longstanding, lo-fi blog, Uhutrust, which she began in 2006. Operating as a kind of parallel inventory or toolbox for her artworks, the blog makes a mockery of artistic self-promotion, whilst rooting her abstract painterly practice in a DIY space outside of the museum and market. Full of observations about tabloid newspapers, pop culture and social media, alongside more diaristic snippets and an eccentric assemblage of photographs, its material is the same mixture of public and private, populist and obscure as is found in her art.

Eichwald has often incorporated graphic, textual or diagrammatic elements within her idiosyncratic abstraction: Untitled (2019), for example, which produces a kind of flow chart on a pink ground; or Deutsche Bahn (2019), which reinvents the corporate logo of the German railway company. This pick and mix of sources and appropriated styles relates her painterly practice to her collage work. But Eichwald’s latest paintings seem more comfortable in their abstraction. They are as confident and easy in their conversations and confrontations with art history’s genres and giants as they are with their own material imaginaries.

Michaela Eichwald's 'Auf das Ganze achten und gegen die Tatsachen existieren' is on view at Kunsthalle Basel until 23 January 2022.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 222 with the headline ‘Cologne State of Mind', as part of a special series titled 'Painting Now'.

Main image: Michaela Eichwald, Auf das Ganze achten und gegen die Tatsachen existieren (Pay Attention to the Whole and Exist Against the Facts), 2020, acrylic, lacquer and shellac ink on pleather, 130 × 287 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Maureen Paley, London