Mike Kelley and the Ghost of le Comte de Lautréamont

On what would have been Kelley’s 66th Birthday, Gabriella Pounds explores the impact of the antic French poem ‘Les Chants de Maldoror’ on the artist and his predecessors, from Hans Bellmer to John Balance

On what would have been Kelley’s 66th Birthday, Gabriella Pounds explores the impact of the antic French poem ‘Les Chants de Maldoror’ on the artist and his predecessors, from Hans Bellmer to John Balance

Isidore Ducasse, better known as le Comte de Lautreámont, was a French poet with a literary corpus as slight as a will o’the wisp. Born in Montevideo, Ducasse moved to Paris in 1867, where he died three years later at the age of just 24. As Prussian forces besieged the city following the capture of Napoleon III, a concierge discovered the poet in his Montmartre hotel room, white as a ghost. Ducasse left a single complete work in his wake: a prose poem titled Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror), published pseudonymously in 1869. A strange soul, he wrote only at night, seated at a piano, reciting draft sentences interspersed with chords.

Critics contend that Ducasse adopted his pen name due to Les Chants de Maldoror’s obscenity. In letters to his publisher, dated 1869, Ducasse explains: ‘I have written of evil […] as [John] Milton and [Charles] Baudelaire, etc. have all done’ but ‘more vigorously’. Across six cantos of grotesquerie, the eponymous misanthrope (mal d’aurore translates as ‘dawn’s evil’) flees a policeman’s platinum torch beam and spirals through dream-like realms. Parodying bourgeois contentment, Maldoror cuts his cheeks to create a permanent, satyr-like smile. In pristine waters, he pursues a ‘hideous coupling’ with a shark. Brutality’s nadir, however, occurs when Maldoror encounters Mervyn, a young English rose who enjoys fencing. Tormented with forbidden longing, he shoots Mervyn and ties his limp body to the Paris Panthéon.

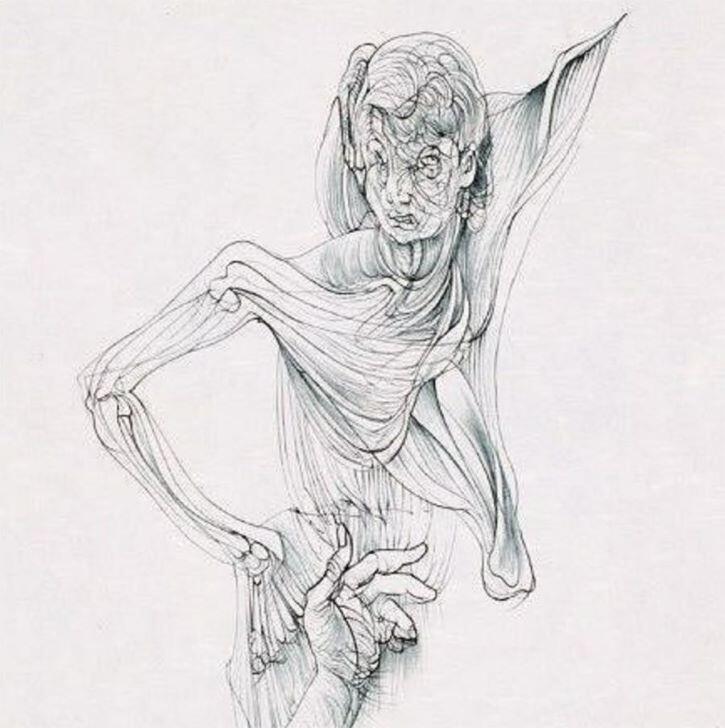

A satire of 19th-century realist novels – with the death of Mervyn allegorizing the genre’s demise – Ducasse’s antic poem has often resurfaced. The author became surrealism’s archangel: André Breton hailed Les Chants de Maldoror’s nightmarish, stream-of-consciousness form as an example of automatic writing; artists such as Salvador Dalí and Man Ray (who received a copy from his erudite first wife, the poet Adon Lacroix) illustrated it. A spartan silverpoint etching by German artist Hans Bellmer depicts Maldoror (1967) as an anime villain, wearing a petal-shaped cloak. For the surrealists, Ducasse’s (in)famous simile ‘beautiful as […] a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table’, dropped their odd hearts to their feet.

In 1980s London, magickian and poet John Balance – who, with his boyfriend Peter Christopherson, formed the experimental industrial band Coil – conjured Ducasse’s spirit in founding the transient music venue Bar Maldoror. Allegedly, Coil – with acts such as Current 93 and Nurse with Wound, who also referenced the poet in their work – declared the ‘bar’ to exist wherever they performed: in darkling pubs serving piss-coloured pints. During interviews, Balance, wearing his eternal raincoat, hair shaved to white-blonde grit, described the band’s debut album, Scatology (1984), as neo-surrealism. Its supernatural theme, the baroque transmutation of base matter into gold, recalled the movement’s alchemical affectations, while the 1988 re-edition featured Man Ray’s Monument to D.A.F. de Sade (1933) – a Petrine Cross outlined over a photograph of lunar buttocks – on the cover. The track ‘Clap’, according to Scatology’s sleeve notes, was inspired by Mervyn. Coil, glancing at Ducasse, found beauty in shit.

And, more recently, none other than the late artist Mike Kelley – contemporary fomenter of hot chaos – blended Ducasse’s blasphemy, perversion and dark humour in a three-channel video installation, Profondeurs Vertes (Green Depths, 2006), at the Louvre, Paris. A voice-over of Les Chants de Maldoror’s aquatic romance wove through noxious-green projections of John Singleton Copley’s painting Watson and the Shark (1777). Ducasse’s bestiary seems to whip around Kelley’s oeuvre, snarling. Kelley’s hermaphrodite drawing, Chrome Goddess (2006), seemingly gestures to the only soul Maldoror admires: a sleepy hermaphrodite in the Tuileries, described as ‘a body splitting in two’. In a 2007 interview, printed in California Video: Artists and Histories (2008), about his stratospheric high-school opera, Day Is Done (2006), Kelley states that Ducasse was ‘very important’ to him, especially his ‘inappropriate metaphors’ and ‘nonsensical shifts’ that somehow retain a ‘narrative flow’. The characters in Day Is Done also lurk within Les Chants de Maldoror: a faun, an extraterrestrial, the Harlot of Desolation, vampires and the Devil himself.

Imagine Ducasse knew he had sipped an elixir of immortality. In a prescient note, he wrote: ‘[Maldoror will] be completed after my death’. Today, Julien Nguyen and Kye Christensen-Knowles’ paintings invoke Ducasse’s ghost, illustrating his mythological beasts in textures of melting chrome. I picture it beneath Notre Dame’s gargoyles, his shadow falling like a cape as he drifts through blades of rain.

Main image: Le Comte de Lautreámont, Maldoror and Poems; book cover: Antoine Wiertz, The Premature Burial, c.1820–28. Courtesy: Penguin