Mohammed Sami Paints the Traces of Trauma

At Camden Art Centre, the artist’s first solo UK institutional show is imbued with latent dread

At Camden Art Centre, the artist’s first solo UK institutional show is imbued with latent dread

Mohammed Sami does not paint people. If figures appear, it is as statues about to be toppled or official portraits shrouded in shadow. Instead, he is an artist of places and things – interiors, cities, clothing, potted plants – and of the traces, both material and psychological, that trauma leaves behind. He is also an artist of memory, allegory and truth. Friedrich Nietzsche’s definition of truth as a ‘mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, anthropomorphisms’ (On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense, 1896) rarely feels far away. Sami imbues each work with latent dread. Born in Baghdad and hailed as a child prodigy, the artist was celebrated under Saddam Hussein’s regime. He now works in London and ‘The Point 0’ at Camden Art Centre is his first institutional solo show in the UK.

A stand-out work is The Praying Room (2021): a complicated composition of extreme light and shade. Sun floods from the right, causing a forlorn plant to cast a threatening shadow, like a Louise Bourgeois spider. The shadow is split across two surfaces – an open door and a pale wall – and your eye dances back and forth trying to make sense of it, each time snagging upon a set of black keys hanging in the door. Only Sami could render keys with such unspoken horror.

Step back a few paces, and the effect is repeated, not just across one painting, but across three. Your eye goes from right to left, starting on an adjacent wall, where light streams like tentacles through a hole blown in a roof (Jellyfish, 2022), then to cables dancing like streamers and casting a lattice of rooty shadows (Electric Issues, 2022), before returning to the spidery projected limbs of the dying plant. It is a compelling moment.

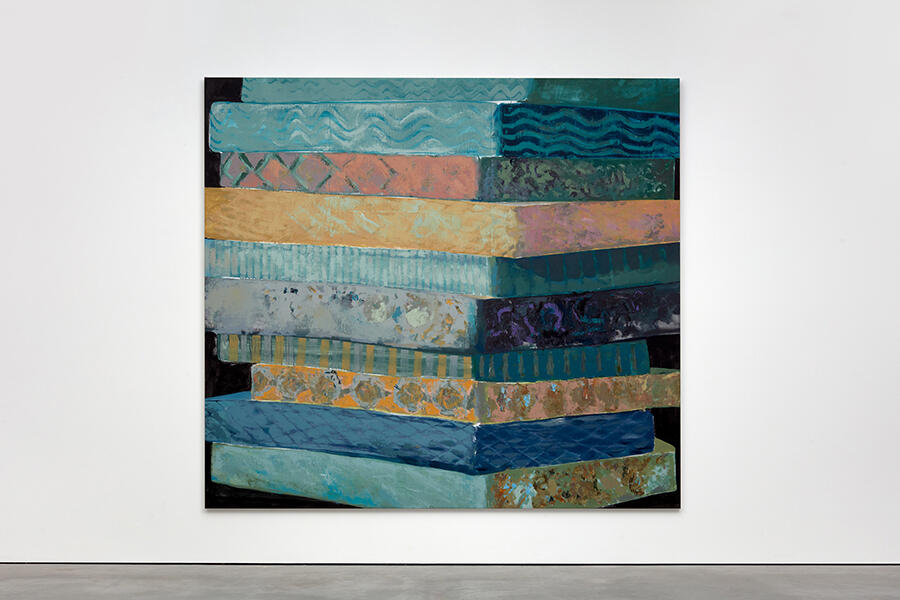

If The Praying Room draws you in through partially open doorways, other compositions do the opposite: they block your access. Ten Siblings (2021) fills the frame with a pile of ten mattresses – striped, quilted or fading floral. (Sami is quite brilliant at evoking threadbare fabrics.) Refugee Camp (2022) includes a house glowing burnished amber and black trees illuminated by stripes of the same harsh light. But these are right at the top. The rest of the painting (nearly three by six metres) is filled with the grey mass of a sheer rock face. Here, what beguiles is not only the subject but the paint itself. That expanse of grey is smeared with fat dabs of caramel and white and crisscrossed with scored lines, lengths of string painted over and removed or left embedded in the surface.

Sami is a profoundly virtuosic painter, adept across a range of scales (such as the surprisingly small Day I, 2022) . In the final room, another huge recent canvas depicts what might be shelves of stacked shirts. But I’m reminded of a wall of sandbags – especially those currently piled up to protect public statuary in Kyiv. I spend a long time sat on the floor in front of it, gazing as whites and dusty pinks slide down towards the base of the canvas, gradually rusting, becoming bloody. There are so many layers here, built up with a dry brush, blurred together or smeared with a palette knife to pool in a thick tideline of crimson and pink. This is flesh, surely. The work is titled Study of Guts (2022).

Sami’s compositions are intriguing, occasionally startling; his handling of paint is frequently thrilling. Often citing the metaphorical writings of the 20th century Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, Sami creates works characterized by visual ambiguity. He paints in similes, some of which, once spotted, do not always sustain interest. However, his best works could ensnare you forever.

Mohammed Sami’s ‘The Point 0’ is at Camden Art Centre, London, until 28 May

Main image: Mohammed Sami, Weeping Walls III, 2022, mixed media on linen, 75.5 x 65 cm. Courtesy: the artist, Modern Art, London and Luhring Augustine, New York