35 Years of Steven Stapleton’s Nurse With Wound

The self-proclaimed ‘purveyors of sinister whimsy to the wretched’ are admirable, not only for a staggering level of productivity, but for being so reliably unpredictable

The self-proclaimed ‘purveyors of sinister whimsy to the wretched’ are admirable, not only for a staggering level of productivity, but for being so reliably unpredictable

[Missing Image]

Why do I love you so? First of all there’s the name: Nurse With Wound. It may vividly suggest another time – the poisoned trenches of World War I, a Hans Bellmer drawing of contorted sensual atrocity. Or perhaps this figure is from a time yet to come, from science fiction that emerges from bloody matter-of-fact – a dazed face seen through a smashed windshield in a j.g. Ballard story. Bellmer and Ballard were, of course, shaped by their firsthand experience of chaos and destruction and, in actuality and metaphorically, postwar Europe remained a minefield with unknown terrors hidden below its seemingly peaceful surface. The world and its inhabitants, particularly in their ability to destroy themselves and others, could never again be taken for granted. More than half a century later, in the ongoing battle we commonly refer to as modern life, people tend to be damaged in unseen, unconscious ways. Nurse With Wound (NWW), as Steven Stapleton’s project has been known for some 35 years now, represents one of the great connections that we still have to the legacy of Dada and Surrealism, to a particular sensibility of horror and bemusement which continues to make art possible and life bearable. In this respect, the title of a collaborative record from 1997, made with Aranos, speaks volumes: Acts of Senseless Beauty. NWW is, without doubt, one of the great creative projects of our time, marked by a consistent engagement yet forever restless, searching and unpredictable.

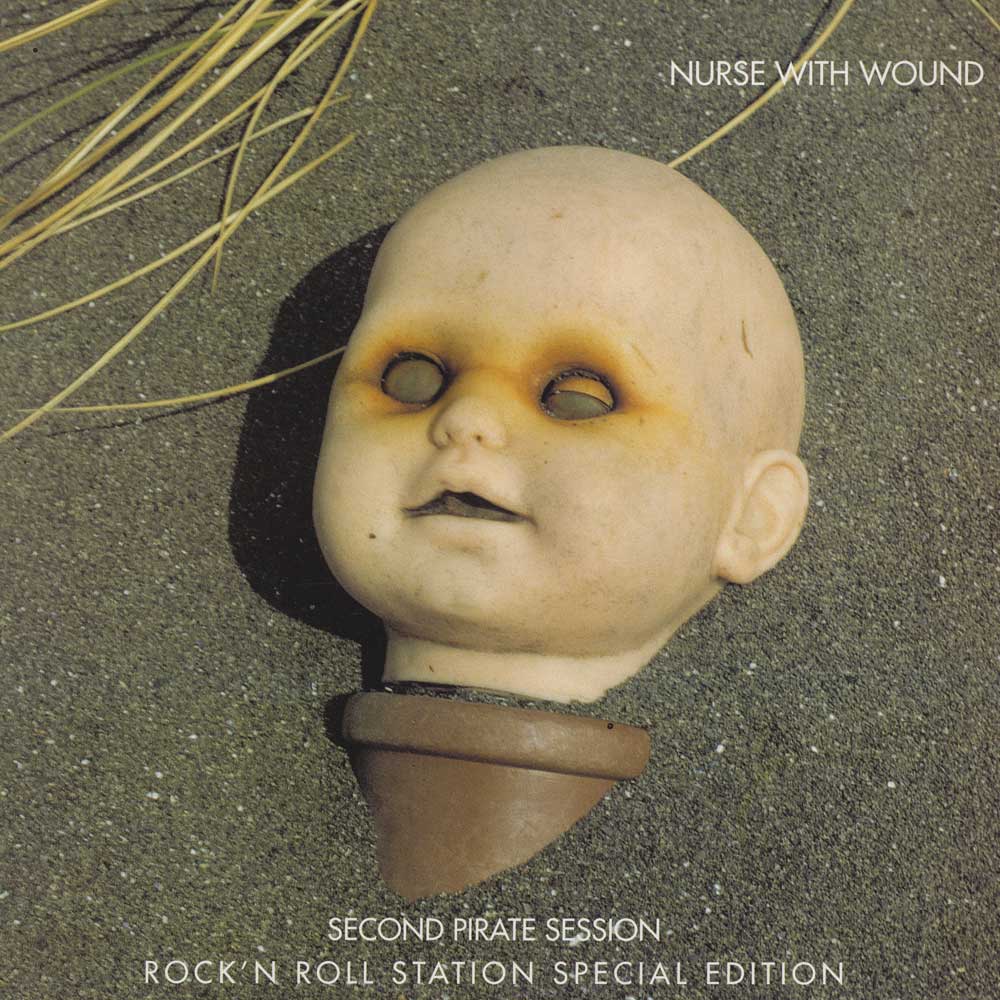

And so I respect NWW for the insistence – despite expectations, occasional animosity and hostility – on being taken seriously, for Stapleton aligning himself under the sign of art and letters, rather than becoming another musical diversion, a mere band. This was announced from the first, with the album Chance Meeting on a Dissecting Table of a Sewing Machine and an Umbrella (1979), a line taken directly from the Comte de Lautréamont’s notorious landmark, Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror, 1869), while evoking Marcel Duchamp’s suggestion: ‘Use a Rembrandt as an ironing board.’ When the covers of nww’s records are placed end to end – all 100 or so, if you have the room, the artwork for which has mostly been done by Stapleton under his favoured alias, Babs Santini – it’s clear that there is a dark and irreverent vision here, not without artistic precedents and contemporaries, and influential to be sure. The list begins but certainly does not end with Francisco Goya, Kurt Schwitters, the Situationists, Martin Kippenberger, Paul McCarthy and Mike Kelley, artists who defy easy categories, and for whom conventions were meant to be upended, lovingly and unexpectedly, used and abused. And somehow, in the process, perhaps in spite of ourselves, we are moved.

[Missing Image]

I’m listening now to Stapleton’s reading of ‘Black Is the Colour of My True Love’s Hair’, as haunting as any of the many interpretations of – and deviations from – the traditional Scottish folk song, including those of Nina Simone, Patty Waters and Davey Graham. nww’s version appears on the album She and Me Fall Together in Free Death (2003), whose cover artwork features a desultory stuffed bear – more love hours than can ever be repaid? – poignantly framed behind wire mesh ‘bars’. It is at the intersection of visual, textual and audio layers that nww opens up an emotional space in which the viewer/listener may become unmoored, whether pleasurably lost or claustrophobically trapped. The low moans and brittle, chattering anxiety that build across seven minutes of ‘Mutilés du Guerre’, for example, from 1981’s Insect and Individual Silenced, may be more than some listeners are willing to endure. That the piece ends with a banjo and choral recording of ‘Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring’ is only a brief reprieve rather than a lulling coda, as it’s nosed out by the squealing snouts of animals who sense they are about to be slaughtered. This sort of auditory experience forces us to reflect on how we are all, in the end, destroying and desiring machines, each bound up in the other. That’s certainly a take on NWW which appears to fit perfectly in one moment, and is wholly inappropriate, even laughable, in another.

I admire NWW, the self-proclaimed ‘purveyors of sinister whimsy to the wretched’, not only for a staggering level of productivity (Stapleton seems to release a new record every six or so months), but for being so reliably unpredictable. Whatever you think you know about nww will likely be confounded by whatever appears next. Having produced over the years music which has been termed experimental, industrial, dark ambient, noise and drone, you come to appreciate how none of these prove in any way, or only temporarily, useful because of Stapleton’s approach, his willingness to collaborate, and how he avoids being pinned down. If musical terms at least offer a handle by which to grasp a substantial and at times elusive body of work, think of NWW as a door with many handles, opening out onto all sorts of rooms, all of which are connected and discontinuous at various points in time. Having made records with David Tibet and Current 93, Jim Thirlwell, the Hafler Trio, Stereolab, Faust, Cyclobe, Jim O’Rourke, Andrew Liles and Sunn 0))), among others, Stapleton and his more recent/frequent partner-in-crime, the engineer Colin Potter, keep NWW fluidly moving in directions even he can’t anticipate: continuity somehow wrapped around an element of surprise. In both art and music there is too often a demand for a signature, recognizable style, and while Stapleton successfully resists this kind of trap, you can see how with NWW he is able to both expand and contract the territory he covers, and still manages to leave his fingerprints behind. Within this freedom of movement he can go just about anywhere really, and, true to his iconoclasm, he has.

While so much of what is termed ‘experimental’ falls into a formulaic mode, NWW never had a formula to begin with, and never had a specific destination. And so you’ll get a relatively easy listening record inspired by 1950s and ’60s lounge music (the wonderful Huffin’ Rag Blues, 2008), and then be confronted by some very uneasy listening, a recording meant to capture what happens ‘in the brain during the last hour and three minutes of a life after suffering a major stroke’ (Ruptured, 2011, a collaboration with Graham Bowers). His recording with William Bennett of Whitehouse, The 150 Murderous Passions (1981) – the reference is to Sade – may very well clear a room within minutes, but Stapleton’s Soliloquy For Lilith (1988) will leave you entranced. You could say that he has nurtured what artists should, but don’t always, have: an evolution. And the man has patience. For all its aerated buoyancy, Huffin’ ... took about four years to piece together. Most audaciously, Stapleton has for quite a while promised/threatened to release an NWW rap album, which, in a 2008 interview, he described as a ‘very, very dark and abstract Nurse With Wound album, but […] completely saturated with female rap, which I love. But it’s a very strange juxtaposition of styles, I can tell you.’ (Missy Elliot, come on down!) Four years later, his fans, who will either be delighted or aghast – Stapleton couldn’t care less – are still waiting. In the meantime, a book devoted to Coil, Current 93 and NWW, the long out-of-print, England’s Hidden Reverse: A Secret History of the Esoteric Underground, by David Keenan, will be reissued by Strange Attractor, and Rotorelief have a new release just out from Stapleton & co., Chromanatron. And there’s always the back catalogue to endlessly explore. One of the reasons I continue to be so fascinated with this project is how it allows you to get inside and outside of yourself – it’s head music and body operating at the same time. And of course it puts a smile on my face when someone asks, ‘What on earth are you listening to?’ and I innocently reply, ‘The Musty Odour of Pierced Rectums.’ Or when a friend says, ‘That’s fantastic. What is it?’ And I’ll answer, ‘A Handjob from the Laughing Policeman.’ What’s not to love?