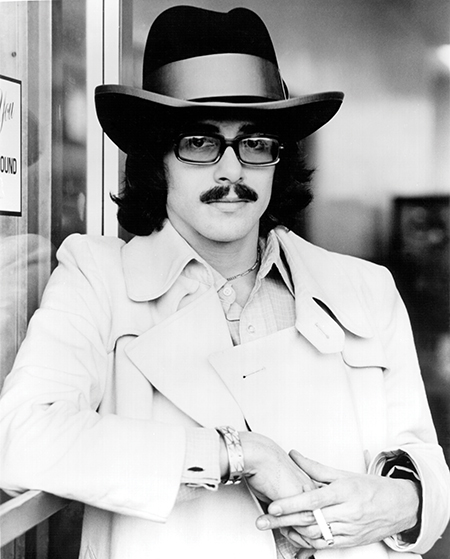

Music: Van Dyke Parks

50 years of Van Dyke Parks

50 years of Van Dyke Parks

Written as the us financial system was recovering from the Panic of 1907, caused in part by the wagering of high-risk futures in unregulated ‘bucket shops’, ‘Wall Street Rag’ (1909) was one of Scott Joplin’s last instrumental pieces, a product of the Missouri-born composer’s frequently impoverished final decade in New York. (With the exception of 1899’s trend-setting ‘Maple Leaf Rag’, ‘Wall Street Rag’ was the only one of Joplin’s compositions to be recorded during his lifetime, piano rolls being another matter.) The first of its four sections (‘strains’, in the parlance) is the most rhythmically varied, and the last is the liveliest; even played at ‘Very Slow March Tempo’, as the score indicates, the piece has a pulse. Still, one might be pressed to hear the (averted) crisis in the music, if it weren’t for Joplin’s programmatic section-labels: ‘Panic in Wall Street; Good times coming; Good times have come; Listening to the strains of genuine negro ragtime, brokers forget their cares.’ There is less comfort and resolution in the nervous 16th-notes and glancing dissonances of this finale than Joplin’s dry annotation suggests.

Van Dyke Parks’s ‘Wall Street’, from his new album Songs Cycled (Bella Union Records, 2013), is a song, not an instrumental work, and it may not be meant to call Joplin’s piece to mind, but I wouldn’t want to bet against it. Since the mid-1960s, Parks has consistently explored the collision points between Western classical music’s timbral and harmonic languages and a World’s Fair of vernacular styles, first as Brian Wilson’s collaborator on ‘Heroes and Villains’ (1967) and the doomed masterwork Smile (which was begun in 1966, but only finally released in 2004), and later as film composer, producer and arranger (Phil Ochs, Rufus Wainwright, Joanna Newsom), and occasional solo artist. Songs Cycled is Parks’s eighth album in 45 years, and his first since 1998 (Moonlighting: Live at the Ash Grove). Besides friend and contemporary Randy Newman, no currently active ‘popular’ musician has caught the same trade-winds with comparable skill and pointed historical awareness. To make these connections more concrete: phrases from Joplin’s ‘The Entertainer’ (1902) course through Parks’s arrangement of Newman’s ‘Vine Street’, the opening song on Parks’s 1968 solo debut album Song Cycle – a now-legendary succès d’estime to which his current album, as the title suggests, makes frequent reference.

With a rich string arrangement backing Parks’s voice and piano, this ‘Wall Street’ alternates between a ragtime-era bounce and something more sombre and less easily defined, while its characteristically vivid lyrics are, at times, as dense and assonant as those of a showtune. ‘I can see nothing but ash in the air / Confetti all covered with blood,’ Parks sings, adding, a few lines later, ‘And in the confetti is human desire,’ along with a pair of lovers, ‘two flaming birds’ plummeting to earth. Written after 9/11, while his daughter was at college in New York, but well in advance of our own Panic of 2008, the song’s perspective on ‘the jewel-encrusted, mud-flattened Hudson’ now can’t help but link one concentrated moment of human tragedy with the ongoing – not to say eternal – destructiveness of capital’s ostinato of boom and bust. ‘Wall Street’ first appeared last year, as part of a limited-run series of seven-inch singles, with cover artwork by Art Spiegelman (closely related to his 2004 graphic novel, In the Shadow of No Towers). Its B-side, also found on Songs Cycled, underlined Parks’s critical intent: a cover of ‘Money Is King’, written and recorded in 1935 by Growling Tiger (Neville Marcano), the most politically forthright calypsonian of his day.

‘Money Is King’ also revisits Parks’s longstanding obsession with Carribean, and especially Trinidadian, music. He devoted most of his 1972 album, Discover America, to the topical calypsos of the 1930s and ’40s, songs recorded and released by American companies like Decca, marketed in their countries of origin, and largely known in the us through West Indian immigrant communities and the souvenir purchases of returning gis. Retaining the patois lyrics of Fitz MacLean’s ‘FDR in Trinidad’ (1937), popularized by Attila the Hun (Raymond Quevedo), and The Lion’s ‘Bing Crosby’ (1939), Parks’s radical, sometimes arrhythmic arrangements add another valence to the genre’s already complex cross-cultural circuitry. Another pet project of the 1970s was Parks’s production work with the Esso Trinidad Steel Band (recently reissued on his own Bananastan label). On Songs Cycled, the counterpart of ‘Money Is King’ is an arrangement of Camille Saint Saëns’s ‘Aquarium’, from the 1886 suite The Carnival of the Animals, which substitutes the massed steel-drum sonority – 23 panmen strong – for the original orchestration’s glass harmonica. According to Parks, the combination ‘underscored my new understanding of the relationship between our marine environment, oil and world power’; in this light, the group’s nominal sponsorship by petroleum giant Esso, a British affiliate of Standard Oil now subsumed in most countries under ExxonMobil, is anything but incidental.

Much of Songs Cycled tours the stations of Parks’s singular career, most directly on ‘The All Golden’, written when he was 24 and first heard on Song Cycle itself. The new one-man vocal-piano-accordion rendition peels back the tape manipulation and Ivesian superimpositions of the 1968 version, clarifying the song’s melodic quotations from Julia Ward Howe’s ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ (1861), while leaving the lyrics’ compound of la bohemia and agrarian idyll as unstable as ever. (The title phrase, as Parks explains in Richard Henderson’s 2010 book on Song Cycle, published as part of the 33 1/3 series, comes from Farm Ballads, an 1873 volume by the once-bestselling children’s poet Will Carleton.) The newer material has a retrospective cast as well, though the melancholy of Parks’s own self-explanatory ‘Hold Back Time’ (which originally featured on Orange Crate Art, his 1995 collaboration with Wilson) is more characteristic than his cover of the lighthearted ‘Sassafrass’, by the prolific country songwriter Billy Edd Wheeler. (Wheeler’s cover art for his song’s earlier vinyl release is reproduced in the booklet for the current cd, as are similar contributions by Charles Ray, Ed Ruscha and others.)

The choral ‘Amazing Graces’ and the instrumental ‘Wedding in Madagascar’ can be appreciated simply for their polished execution and loving respect for the originals’ varied sources. The playful title and jumpy, creolized rhythms of ‘Missin’ Mississippi’, though, are deceptive: there are no ‘Swanee’-style mammies in Parks’s song of the South, only the devastation wreaked on the state – where Park was born, in the coastal town of Hattiesburg – by Hurricane Katrina. The layered stylistic (and self-referential) allusions of Parks’s songs may distract listeners for whom serious content is best expressed through a unified style with a minimum of formal artifice. Nowhere does Songs Cycled flout that assumption more outlandishly or effectively than on the six-minute ‘Black Gold’, which forgoes the Pan-Americanism in which Parks often trades for a theatrically sinister, cello-driven, sea-shanty-cum-Lehrstück that returns to the nexus of commerce, sea and power. By turns, the track evokes Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s ‘Pirate Jenny’ (1928), The Beach Boys’ ‘Sloop John B.’ (1966), Randy Newman’s ‘Sail Away’ (1972) and Parks’s own Tokyo Rose (1989), his timely but barely noticed concept album on colonialism and global exchange. Proceeding from a 2002 oil-tanker spill in the Bay of Biscay that decimated stretches of coastal Spain, France and Portugal, the song begins shipboard with ‘80,000 metric tonnes of crude’ (an accurate estimate of the capacity of the Prestige) and a ‘captain in his cups’. By the second verse, the ship has haemorrhaged, and Parks’s verse is at its highest pitch (‘A rage aroil from the soiled foil of his hull’); in the fourth, the narrator, going down for the last time, doubts that even Christ would care to lead the agents of manmade disaster ‘clear out of this Dark’. It is a gorgeous and dismaying piece of music – and hardly one designed to relax the brokers, even temporarily.