Nam June Paik At Tate Modern Review: How the ‘Father of Video Art’ Became a Prophet

A new retrospective celebrates the artist’s ability to warp technology

A new retrospective celebrates the artist’s ability to warp technology

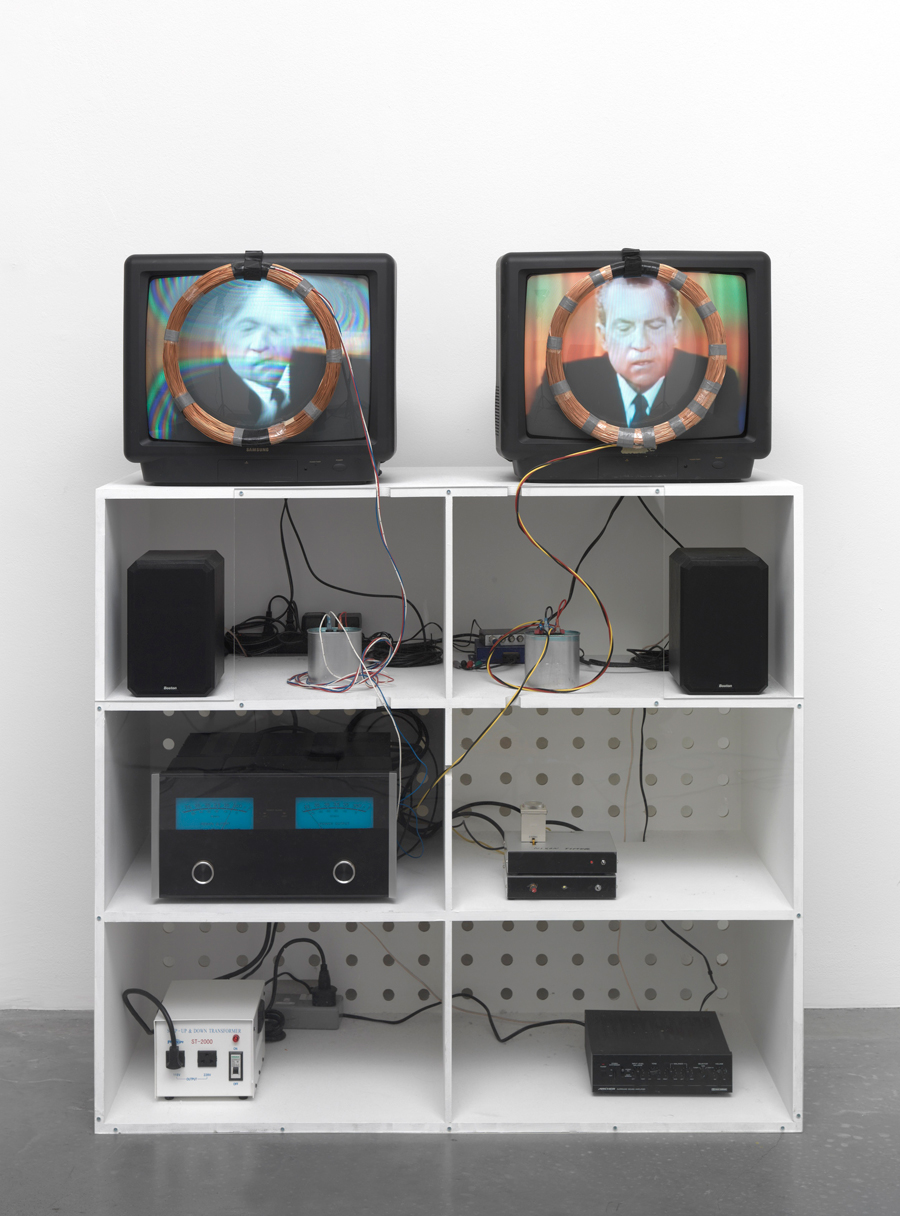

TV wizard. Cathode-ray sage. Nam June Paik is an artist tied in the public imagination to the 20th-century technologies of mass media – the blare of a broadcast behind the beady eye of a convex screen. He’s often held up as ‘the father of video art’, with all the sober paternalism that the phrase implies, but Paik’s work is anything but sedate.

Paik’s status as a pre-internet prophet is both reaffirmed and dissected in Tate Modern’s retrospective: the exhibition does a great job of showing Paik to be a thoughtful, but also impish experimenter; an artist who understood the need simultaneously to engage with and break apart the technologies with which he was working. Much like the splayed Prepared Piano (1962–63), which survives from an early performance, Paik’s TVs are disassembled, augmented, surrounded by wires and shattered electrical panels.

How alien this seems at a time when images are filtered through digital infrastructure, the intangibility of which makes deconstruction difficult. Works like Nixon (1965–2002), with its magnetic glitching of a speech by the former President, and Three Eggs (1975–1982), with its confusion between the real and recorded image, invite comparisons with our own age of media distortion. But there’s also a sense of nostalgia for a time when the warping of reality could be so tangibly grasped.

The exhibition makes much of placing Paik in a social context. This can sometimes see the artist becoming lost in the mix of his famous friends – like John Cage and Joseph Beuys – or bogged down in endless Fluxus documentation. It does show Paik as a generous and prodigious collaborator, particularly with the cellist Charlotte Moorman. But the show’s most powerful works highlight Paik at his most reflective.

In One Candle (Candle Projection) (1989), CCTV footage of a lone candle in a dark room is shown on the walls in blue, red and green. The flame looks so small, so fragile compared to the colourful projections that illuminate the room. As visitors pass by, the flame and its bright copies flicker, threaten to disappear. What is the broadcast without the flame? What is the flame without the broadcast? In the end, all is light.