Neither, Nor: What to Expect From the Italian Pavilion of the 58th Venice Biennale

Barbara Casavecchia talks to the show’s curator, Milovan Farronato

Barbara Casavecchia talks to the show’s curator, Milovan Farronato

Barbara Casavecchia Let’s start with the title of the Italian pavilion: ‘Né altra Né questa: La sfida al Labirinto’ (Neither Nor: The challenge to the Labyrinth). What inspired it?

Milovan Farronato The labyrinth is a place ruled by extreme rationality, but it’s also an emblem of disorientation – a fascinating paradox. Reading Italo Calvino’s novel The Castle of Crossed Destinies (1973) led me to his earlier essay Challenge to the Labyrinth (1962). Then I remembered a show by Katharina Fritsch at the Schaulager in Basel in 2016, in which a small house with three rooms was surrounded by a vast empty space; it freed me from the fear of having to fill the entire architecture of the Tese delle Vergini. There are so many ideas behind that of a puzzle of connecting – or forking, to quote the famous story by Jorge Luis Borges – paths, like the garden of memory, the hortus conclusus (enclosed garden), or the ‘monstrous garden’, holding the Minotaur at its heart. The labyrinth, for me, has less to do with a theatrical apparatus for installing the works, than with the idea of creating more exhibitions at once, that can change in relation to the movements of the spectator. My curatorial practice has often involved open-ended, time-based events, focussed on performance, like the Volcano Extravaganza on the Aeolian island of Stromboli, which I have been curating for ten years with Fiorucci Art Trust. I’d like to offer the public the chance to become a performing agent.

BC The three artists you have chosen for your exhibition have all participated in the Volcano Extravaganza: in 2011, Chiara Fumai with a performance and Liliana Moro with a site-specific installation and in 2013, Enrico David created a wall-painting. Has Stromboli been a key influence?

MF Yes, but also for another reason. In 2016, when I co-curated the Volcano Extravaganza with Camille Henrot, Joana Escoval led a walk on the slopes of the volcano. She interrupted it halfway to explain we could either take the path to the Observatory, or take a right turn and follow her downwards, amid the wild bushes. By following her, I lost sight of both the top of the volcano and also of the sea, suddenly realizing, after a decade of frequent trips, that I was seeing the mountain’s body for the first time. I learned how important it is to see things from a different angle.

BC So was Italian art the mountain you had to explore from a different perspective?

MF When I was invited to submit a project for the pavilion, I was also specifically requested to create links between the past and the present, so I chose three presences from different generations. Liliana (born in 1961) and Enrico (born in 1966) are close in age, but Liliana has deep roots in Milan and has never left the city. Enrico, on the other hand, was born in Ancona, but after being turned down by a local academy he moved to London to study at Central Saint Martins. He is hypertrophic, generous, extremely prolific and channels the images that populate him into a specific vanishing point. Liliana is the opposite: she condenses everything into a very few, very thoughtful works that are open to a multiplicity of readings.

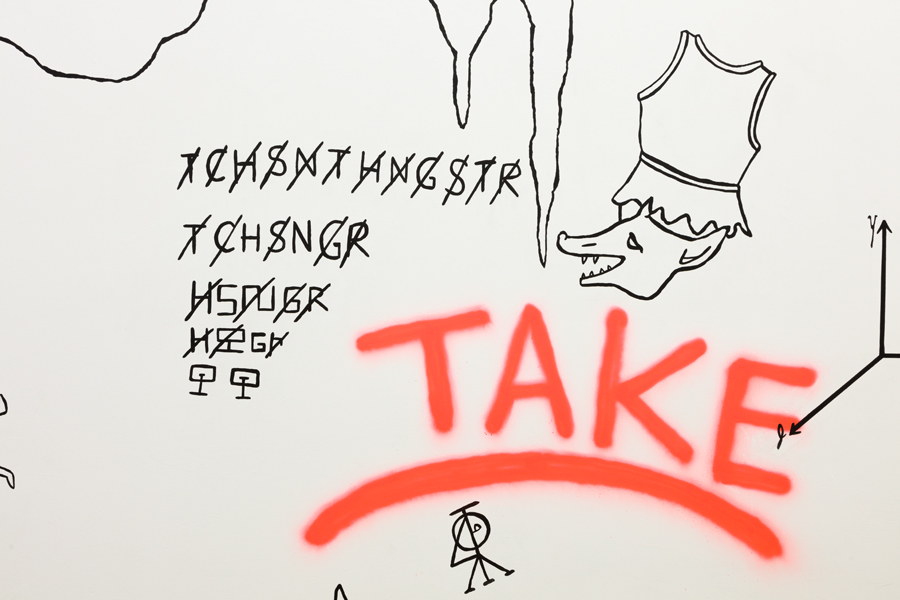

Chiara (1978-2017), who was younger is, somehow, my way out of the labyrinth, because her presence undermines a binary logic and at the same time connects the other two participants. She will be present with a large mural, which we had worked on together for over a year, before she chose her own extreme way out. She drafted a long series of instructions for the piece and referred to it as la grotta (the cave): an image frequently associated with alchemical symbols and occultism, one of Chiara’s recursive fields of enquiry, and increasingly present in her thoughts at a time when her speculative system was showing signs of crisis.

BC How will you present the mural?

MF Precisely as Chiara imagined it. We had set aside many detailed images, which now provide the score for its realization in the Pavilion by Micki Pellerano, an artist close to Chiara. I remembered she had proposed a title, but I couldn’t find it, so I had to go through all our correspondence, with the help of my assistant Marina La Verghetta – it was too intense and emotional for me to do alone. And finally, in an email sent on 31 December 2016, with many wishes for a happy new year, there it was: ‘This last line cannot be translated’.

BC How many of the works are going to be new?

MF Enrico will show new and recent works, while Liliana’s selection will range from 1988 to today. The exhibition display, designed with Studio Julia, should work as a pliable and flexible support. A diagonal wall with two entrances will make it possible to resist a linear chronology and narration.

BC What role has politics – including Italian current politics – played in your thinking?

MF Even though I live in London, I have never lost interest in Italian politics, although my perspective is more frequently from a small island in the South than from a big city like Milan, where I still retain my residence. Italy is a place of complexity and, like Stromboli, a dangerous but also fertile one. For a decade, I operated as director of a Milanese non-profit space, Viafarini, and looked at hundreds of artists’ portfolios, an experience that shaped my perspective on Italian art and society at large. That’s how I first met Chiara and also Anna Franceschini, who I have commissioned to make an experimental film that will embody the idea of the pavilion, instead of just documenting it. Whilst the show is not overtly political, it’s also true that many of the works can be interpreted in political terms. Liliana’s neon né in cielo, né in terra (neither in the sky nor on earth, 2016) is both a quotation of a common Italian expression and a poetic image, that situates the artist in relation to the public sphere. Some of Enrico’s sculptures are political in their posture and resignation. In Chiara’s work I read the issues of feminism and patriarchal critique.

But I should point out that although I am not exactly the most reassuring subject from the viewpoint of an institutional profile, I was appointed and granted carte blanche by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Art and Architecture and Urban Peripheries, directed by Federica Galloni, as well as by the Minister of Cultural Heritage Alberto Bonisoli.

BC Is queerness a visible or implicit part of your work as curator of the Italian Pavilion?

MF In an exhibition, even if a work clearly stands out, you may prefer not to place it in the spotlight, so that other works and nuances can emerge. In the case of the Italian pavilion, it’s not that I have set queerness as an objective. To support ‘neither, nor’, as well as to look for a third way that does not deny others but allows them to coexist, could be clearly interpreted as a stance, but to me it’s not a goal. I think that if one plays on multiple fields, lives are richer.

‘Neither Nor: The challenge to the Labyrinth’, the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale runs from 11 May until 24 November 2019

Main image: Enrico David, Ultra Paste, 2007. Courtesy: Collection Nicoletta Fiorucci, London