Remembering Designer and Artist Enzo Mari (1932–2020)

The creator of ‘allegorical’ exhibitions, who believed in the potential of mistakes, has died aged 88

The creator of ‘allegorical’ exhibitions, who believed in the potential of mistakes, has died aged 88

Enzo Mari was a notoriously difficult man. Notoriously sharp, too: like the sickles he loved to collect and exhibit as the epitome of functional design, superlative craftsmanship and working-class pride. Artist, designer, architect, theorist, teacher, curator, public intellectual and self-confessed utopian, Mari was labelled ‘the critical conscience of design’ by fellow designer Alessandro Mendini. If the main activity of a conscience is moral reflection, then the title was well earned.

Mari’s passion for design was his way of changing the world by giving it a better shape. He always weighed up the costs of industrial production in terms of both human labour and planetary ecocide. He once invented a new joint for the Java sugar bowl, produced by Danese in 1968, to obviate, for the factory worker, the alienating repetitiveness of inserting a linchpin into the lid.

He could spend years working stubbornly on a single project, taking the time to understand the good and discard the bad, ugly and foolish. In 2010, when I collaborated with him on an exhibition and book titled ‘60 Paperweights’ – one of Mari’s philosophical ‘allegories’, as he defined his installations – he taught me that the essence of all intellectual work lies in the capacity to say: ‘NO, NO, NO!’ Because it’s only by piling up mistakes, refusals and alternatives that a good idea and beautiful form can emerge.

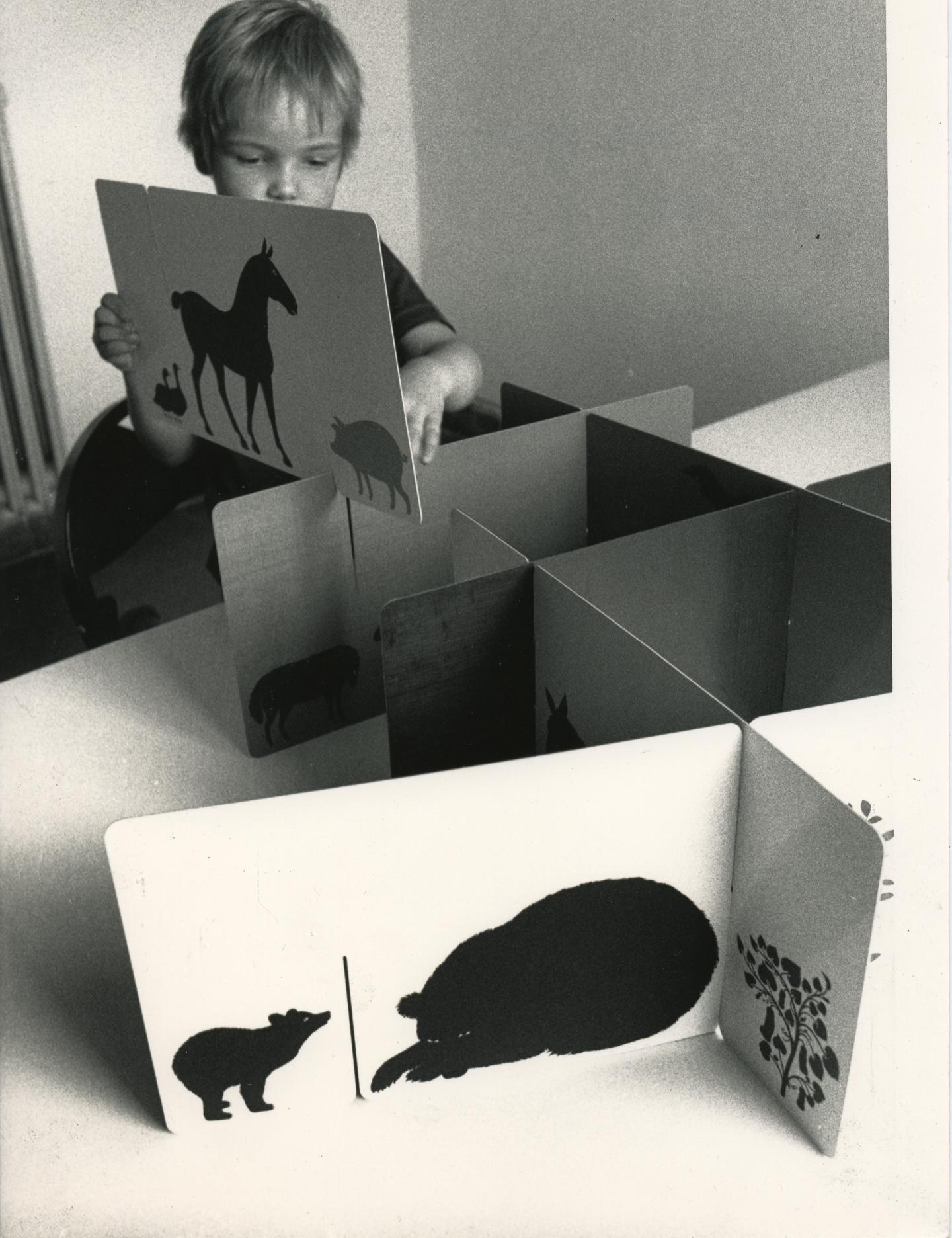

In his foundational manifesto for arte povera, ‘Notes on a Guerrilla War’ (1967), Germano Celant took Mari, Jerzy Grotowsky and Andy Warhol as examples of how to disregard the ‘visual coherence’ idolized by the art system for what he termed ‘interior coherence’. A year later, Mari refused to participate in the 34th Venice Biennale and in Documenta VI, while taking part in the student protests and occupation of Milan’s Triennale. The same institution is now hosting (until 18 April 2021) his largest retrospective to date, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and designer Francesca Giacomelli, Mari’s long-time archivist. It opens with his first programmed and kinetic artworks from the early 1950s, conceived as models for the study of visual perception, and with the first, wonderful books, posters and combinatory toys for children (such as The Fable Game, 1965), aimed at stimulating infants’ freedom of experimentation. Mari believed that all children should be awarded the Nobel Prize at the age of two on account of the incredible knowledge and abilities they absorb, via trial and error, in such a short space of time. I’m sure as a father of three, he deliberately chose the ‘terrible twos’, since it’s the age when children discover negation, through which they affirm their identities.

The art critic Lea Vergine (Mari’s wife, who died just one day after him), found in his early artworks a ‘candour and exasperation’ that accompanied him all his life. Continually developing projects intended to advance individual awareness, Mari was invariably disappointed by their public reception. His most famous such work, the booklet Proposta per una Autoprogettazione (Proposal for Self-Design, after the eponymous 1974 exhibition held in Milan at Galleria Milano), was introduced by a straightforward note: ‘A project for making easy-to-assemble furniture using rough boards and nails. An elementary technique to teach anyone to look at present production with a critical eye.’ The copyright-free chairs, tables and bed designs have been reproduced millions of times, yet Mari maintained that most people failed to understand the thinking behind them.

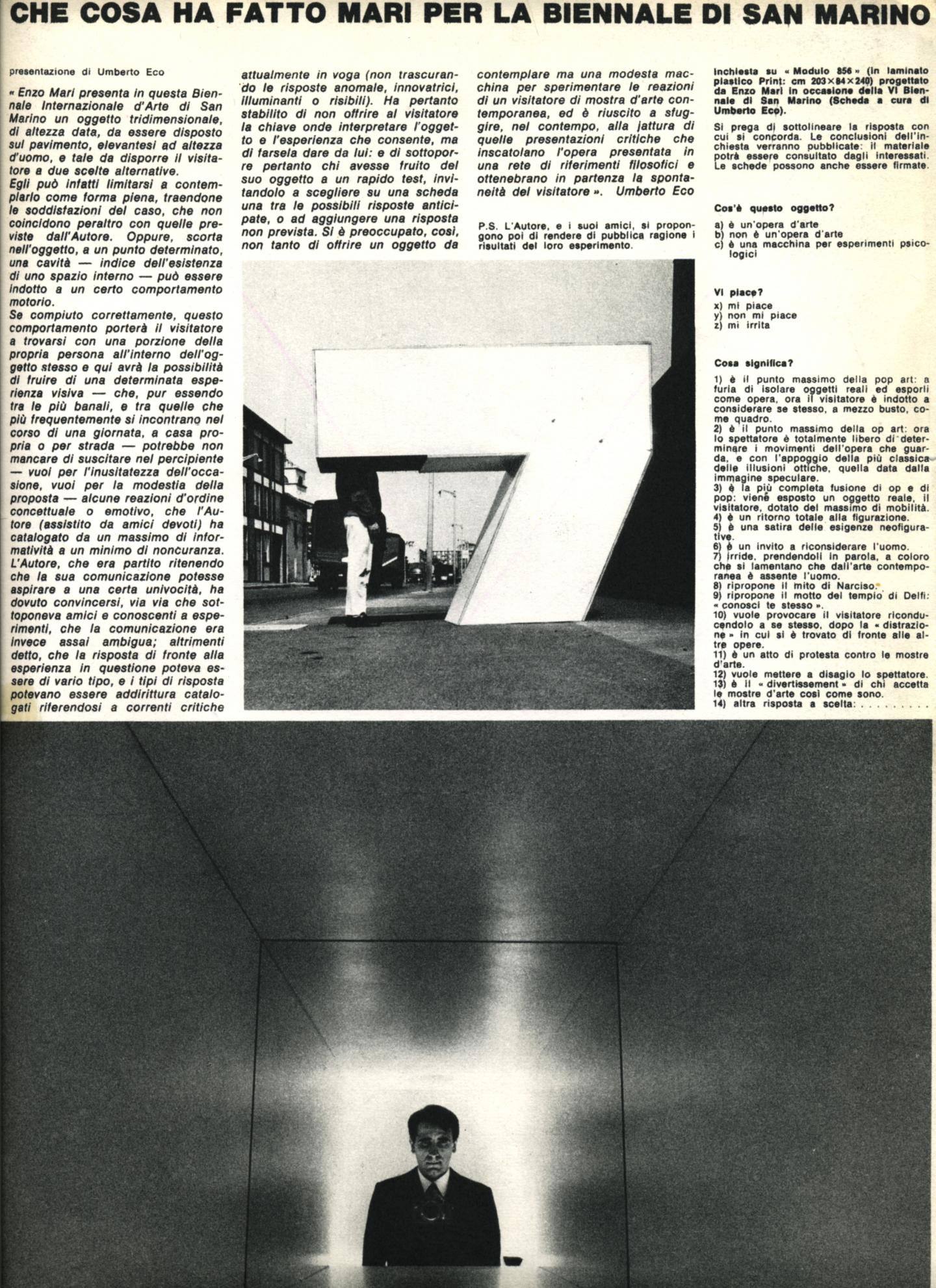

If, according to Lacan, the individual self becomes aware of its existence by recognizing one’s image in a mirror, Mari used the same setting to engage and provoke his audience. Mari used mirrors to engage the viewer’s intellectual curiosity. His first ‘allegory’, Modulo 856 (1967), created for that year’s San Marino Biennale, was described by the Italian semiologist Umbero Eco as a ‘machine to test the reactions of a visitor to a contemporary art exhibition’. Viewers were invited to enter a minimal wooden structure, one at a time, only to find themselves confronted by a mirror paired with a set of fundamental questions, devised by Eco: ‘What is this?’ ‘Do you like it?’ ‘What does it mean?’

Enzo Mari died on 19 October 2020 in Milan, Italy. Galleria Milano paid homage to Mari by restaging his 1973 exhibition, ‘Falce e Martello’ (Hammer and Sickle). ‘Enzo Mari Curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist’ (curated with Francesca Giacomelli) is on view until 18 April 2021 at Triennale Design Museum, Milan.

Main Image: Enzo Mari installing ‘Falce e Martello’ (Hammer and Sickle), 1973. Courtesy: Galleria Milano, Milan; photograph: Aldo Ballo