Nolan Oswald Dennis

Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

Two years ago, in an interview with the webzine 10and5.com, Nolan Oswald Dennis spoke of his youthful aspiration to be a writer, ‘in the graffiti sense as well as the literary sense’. Dennis – a trained architect who was born in the Zambian capital of Lusaka to a family of South African political exiles – has found a productive middle ground in his ambitiously scaled wall drawings, an iterative version of which forms the key backdrop to his probing, grey-scaled debut solo exhibition, ‘Furthermore’, with Goodman Gallery.

Dennis has been producing his ephemeral wall drawings for a while now. In 2013, he created a 300,000-word installation that examined five centuries of South African land and conflict for the multi-media exhibition ‘Land’. His wall drawing took four days to complete, in a corridor of Cape Town’s retired City Hall, and included a verbatim rendering of the Natives Land Act of 1913. ‘The static record is by definition insufficient,’ he said at the time of his interest in reanimating archival texts as quoted fragments.

That same year, he illustrated the Johannesburg avant-garde musical outfit The Brother Moves On’s debut album A New Myth (2013) with an Afrofuturistic-like cartoon of an astral shaman. This tension between the sinew of figuration and abstractedness of words and symbols recurs in his solo exhibition, which includes various ink drawings, a video describing the protocols surrounding the national flag and an internally lit rectangular sculptural form covered in a grey blanket and named after irresolvable contradiction, Aporia II (2016).

Given the preponderance of abstracted landscapes in his ink and collage drawings, it is helpful to know that the form of his 2013 wall drawing resembled a linear topography. Last year, as part of his participation in ‘Young, Gifted and Black’, a group exhibition curated by artist Hank Willis Thomas, also at the Goodman Gallery, Dennis created another cartographical word-scape. The horizontally drifting black and gold sentences in this work mused on free jazz, masks and black magic, while also dissecting colonial contact and the fraud of racial reconciliation.

Produced in a purposefully limited colour tone, Dennis’s wall drawings offer more than just cant political sloganeering by an analytical young artist who has allied himself to the student civil disobedience gripping South Africa. His ephemeral wall drawings have functioned as a kind of personal tutorial. Digging around the muck of the past, drawing equally and impressionistically from sullied official sources and formerly banned documents, Dennis has been attempting, as he put it in 2014, ‘to escape the limitations of my ongoing miseducation’.

Anyone who attended Okwui Enwezor’s ‘All the World’s Futures’ at last year’s Venice Biennale will be familiar with the pitfalls and pleasures of the exhibition as history lesson. Although less fluent in his chosen medium, Dennis’s new and untitled wall drawing bears out the possibilities of what Glenn Ligon described as the ‘tension between the meaning of the words and the form of the paintings’. Spanning two lengths of wall in his solo exhibition, Dennis’s drawing is sparser than previous ones. Composed of verbal fragments, sundered texts and maps, free-floating constructivist lines that recall El Lissitzky and seven obelisks that reiterate the physical forms of his wooden sculptures, the work eschews the landscape idea for something else: a speculative scenography of the past.

The atomized phrases in silver ink are derived from various sources. ‘A paper is a weapon,’ is a quote from the headline of a July 1971 issue of the outlawed South African Communist Party’s news bulletin, Inkululeko-Freedom. Another quote reflects the artist’s gallows humour: ‘You sold us a dream. We are here for our refund.’ The anger undergirding this show is palpable.

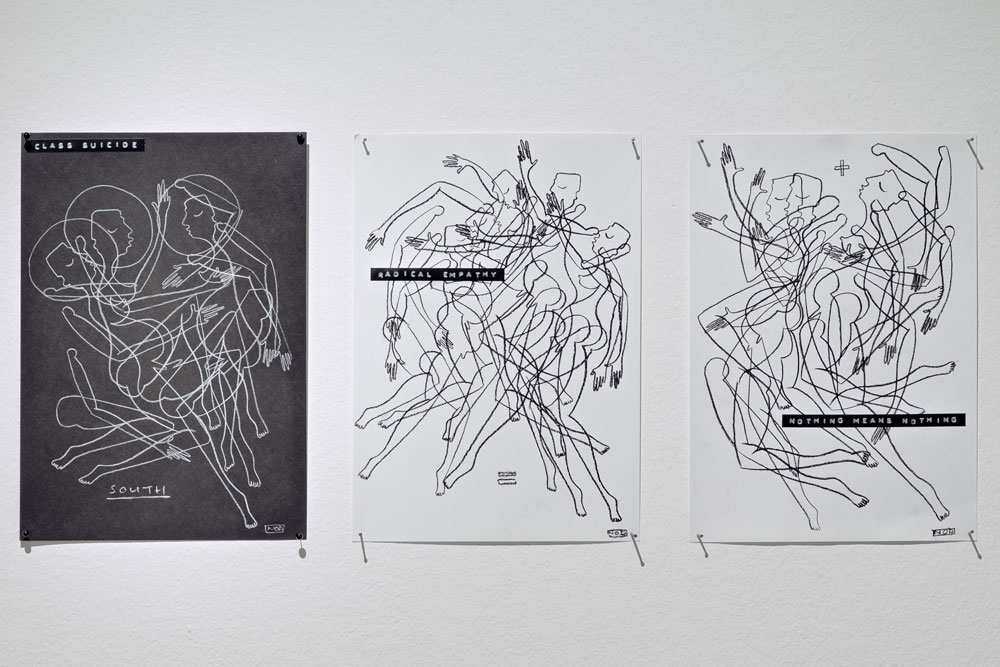

But Dennis is not simply deconstructing the past in this timely, temperature-gauging show. ‘Furthermore’ includes a suite of three ink drawings – Class Suicide, Nothing Means Nothing and Radical Empathy (all 2016) – recycling the shamanic figure from his The Brother Moves On collaboration. Radical Empathy sits in the middle of the grouped display. Its title suggests, at least to me, the foundations of this uncompromisingly urgent, if at times oblique, investigation of a querulous present.