Only the Lonely

Dan Fox talks to Michael Smith about minimalism, comedy and failure

Dan Fox talks to Michael Smith about minimalism, comedy and failure

Let me tell you about my friend Mike Smith. Mike once entered the USA Freestyle Disco Dancing Championship at the Copacabana nightclub in New York City. The year was 1979; punk was in and disco was on the way out. Mike took the competition seriously: he even went to the club before it opened to assess the lighting system and sprung dancefloor. The night of the competition, he wore a baby blue tux and black shirt, and danced alone to Thelma Houston’s ‘Don’t Leave Me This Way’. He came 12th.

Mike’s twirl under the mirrorball might be the saddest performance I’ve ever seen. Or one of the funniest. That’s the thing with Mike; you find yourself laughing at him, but also wanting to buy him a beer and tell him that it’s going to be OK. His life is spent behind the curve, forever trying to fit in. He’s tried his hand at everything. He hosted a public access TV show called Interstitial, on which he’d interview artists from New York’s downtown scene about their work. (Mike’s awkward to-camera introduction ran: ‘Interstitial: the place between two places, where ideas and dialogue and opinions come together, intersect or overlap.’) He once built himself a Government Approved Fallout Shelter and fitted it with a snack bar. Mike has run a concert lighting company and tried to start an artist’s colony and ‘wellness centre’. He has taken photography lessons with William Wegman, attempted to memorize two words from the dictionary every night to improve his vocabulary, and invented a new game for kids called ‘Take Off Your Pants!’ I call him ‘my friend’, but Mike’s almost always alone. Mike is one of life’s innocents, approaching the world with sincerity and optimism. He’s a born loser.

But Mike Smith, you must understand, is not the same as Michael Smith. Michael Smith is a New York-based artist and master of tragicomedy. For the last 40 years, Smith has been making video and performance work that uses alter egos such as Mike, and the disturbingly overgrown Baby Ikki, to explore the absurdities of consumerism and the insecurities of creative life. Working in collaboration with artists and directors such as Mark Fischer, Mike Kelley, Doug Skinner and Joshua White, Smith plays with sitcoms, TV chat shows, documentary film, performance art, puppet shows and promotional business videos to create a vision of the modern world that is sad, poignant and downright hilarious.

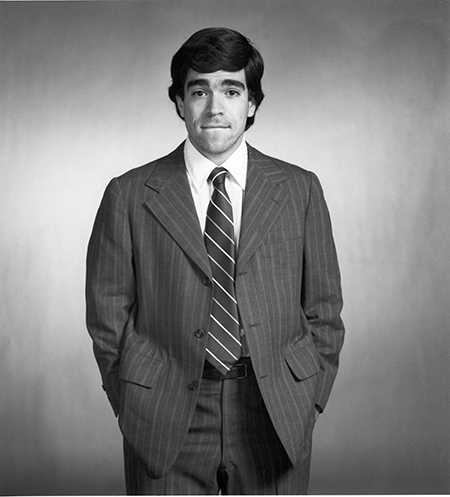

I visited Smith at his New York studio as he prepared for his first UK solo exhibition at Tramway, as part of Glasgow International, In April. He asked that I make him sound good, so I suggested describing the trophies and photographs of him posing alongside celebrities and world leaders that line his studio walls. I also suggested telling readers that his studio is a penthouse apartment on the Upper East Side and that, throughout the interview, he drank champagne in a hot tub, whilst taking calls from his financial advisor about the large profits netted from his latest sales. Unsurprisingly, for an artist whose work describes loneliness, failure and disappointment, he didn’t go for it.

Dan Fox How did it all begin?

Michael Smith I got into art through my brother, Howard, who is an abstract painter. I took a class with him and jumped right into painting. I didn’t have a conceptual background, but I had a real sense of space and balance. I started to make abstract expressionist paintings and I was kind of precocious. I was accepted into the Whitney Independent Studio Program in New York City when I was still 18. A few years later, when I was living in Chicago, my painting hit a dead end. It got so reductive that I didn’t know what to paint any more. There was an empty canvas in my studio and it was terrifying. So I started going to a lot of events, primarily dance and performance; it was also a good way to meet people. While in New York, I’d seen work by the playwright/director Richard Foreman, who was a huge influence on me. So was Wegman; his work was so dumb and so smart at the same time, it was great! Seeing art and laughing in a museum was a totally new experience.

Vito Acconci was also an influence. In 1974, because I happened to have a car at the time, a friend asked me to help out with Acconci’s performance at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. I think it was billed as his last live performance. Acconci’s use of language and his voice intrigued me. Around the same time, I started going to this comedy club and was fascinated by stand-up. One day a friend said, ‘Why don’t you do a routine?’ I thought, ‘Why not?’ So, I began working with audiotapes, listening to my voice. I had no material, so I looked out of my window and talked about what was in front of me. Often, it was me talking about getting the tape recorder to work. Eventually, I got the sense of my voice, the tone, the rhythm and my timing. So, I put together something for the club I’d frequented. Fortunately, it closed down before I was able to perform it, as I’m sure I would have bombed.

DF What appealed to you about comedy?

MS The tone in the art world can be so sombre. I’d go to these long events that were interesting up to a point, then I’d get incredibly antsy and bored; often, I’d find myself laughing. Sometimes, what I was seeing was funny, but more often I didn’t understand what I was laughing about; I didn’t know if it was out of discomfort or just the absurdity of the situation, given the reverence that a lot of the work would get. I was intrigued by the idea of going against the grain. I also liked the fact that when I was at a party and someone asked, ‘What do you do?’ I could say, ‘I’m a comic.’ It sounded good. Then they’d say: ‘You’re not funny.’ And I’d reply, ‘Well, I didn’t say I was a good comic.’

DF Did you notice a difference between the way your work was received by art audiences and by people in comedy clubs?

MS Art audiences will watch paint dry. They’ll read meaning into it, which allows you to take incredibly laborious material and make something of it. Also, they’re very patient, so I was allowed to experiment with time – slow, plodding time. It was always a slow build and, usually, very deadpan. There was one comic in particular from my youth who made a big impression on me: Jackie Vernon. He had a monotone voice and a slow, very deadpan delivery. He was also self-deprecating. Wegman’s delivery is very deadpan, too. I was also very much into Buster Keaton and Jacques Tati. Maybe it’s a midwestern thing, but I liked a delivery that didn’t have the loudness and antagonism of other art strategies used around the time of punk. Everybody was being bad or doing something loud with bells and whistles. I saw my work as other than that. I think some of our targets were the same – the homogenous middle class or absurdities in our culture – but I tried to attack it from the inside.

DF Did your interest in timing relate to minimalism?

MS Well, I use repetition and extended time. I like to create a sense of tension, hopefully without going too long or too far, when it becomes boring. It’s a matter of timing.

DF You’ve mentioned Acconci, Foreman and Wegman. Who else were you looking at?

MS I’d go to a lot of minimal and pedestrian movement dance performances – basically what everyone else was looking at. I was also interested in many of the performers who were included in the recent show at the Whitney Museum, ‘Rituals of Rented Island’, in particular Stuart Sherman and John Zorn. I felt very connected to their object performances. I’d see a lot of things, all very different from the Clement Greenberg stuff I was looking at before I moved to New York – although I still like looking at that kind of painting.

DF Do you feel you’re working in that Greenbergian lineage today? [Laughs]

MS Definitely! I’m part of that trajectory. [Laughs]

DF Baby Ikki reminds me of Ted Post’s 1973 horror movie The Baby, about a family that keeps a grown man in a state of perpetual infancy. When did Baby Ikki first appear in your work?

MS In 1975. In my first performances I would refer to myself as Mike, but the character, the persona, of ‘Mike’ didn’t appear until Down in the Rec Room in 1979, when I put him into a narrative structure, gave him an outfit and a voice. The baby was a reaction to a lot of feminist activity and discussion about gender at the time. I started thinking about what it would be like to have a character without gender, and I thought of an infant. People may take offence at this but, with babies, I don’t think of them as a little boy or girl, they all look the same to me. The name Ikki plays on ickiness, and the palindromic name made me think of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu the King [1896], which I was reading at the time. I had in mind an image of this baby walking and going through a gamut of experiences. Ikki talked at first, and then I eliminated the language and it just became about movement.

DF What has Baby Ikki allowed you to explore?

MS It allowed for direct interaction with the audience, and it was a crowd-pleaser. I do it well. It’s weird and eerie, and it gets at people. With the Mike character there is pathos, but the baby elicits a combination of repulsion and concern. Currently, I’m working with the theme of the fountain of youth, bringing the baby and Mike together in a loop: Mike feeds into Ikki and Ikki feeds into Mike. I go from one character to the next, like a life cycle.

DF The baby is generally a figure people want to care for, even though they might be repulsed by Ikki. Normally, a baby is indulged for making mistakes or blundering into situations. To what extent do you think Baby Ikki is a reflection of what an artist is? Someone who is indulged for their transgressive behaviour?

MS I like that analogy. I mean, I haven’t had the baby playing with his shit or anything – that frightens me – but there’s definitely an indulgence with artists, and some of my work satirizes things that go on in the art world. I’m not real big on art about art, but I somehow continue to make it.

DF In A Voyage of Growth and Discovery (2009), which you made with Kelley, Ikki goes to the Burning Man festival, and mixes with festival-goers who are in search of personal liberation. And in The QuinQuag Arts and Wellness Centre Touring Exhibition (2001), you create a fake TV news segment about Mike starting an artist colony-cum-wellness centre. There seems to be a theme of self-improvement that runs through the work.

MS Well, I would like to improve! [Laughs] We’re constantly trying to improve, being sold the idea that we can. Within our society, there is an idea that everyone has potential, but in reality this hope of a meritocracy is usually false. With QuinQuag ... I invented an art colony that was basically the hobby of a rich woman. Sure, everyone had great intentions and creativity was at the centre of it all, but the artists attached to the colony knew they had a good thing, so they played along with their host in order not to lose their summer vacation spot. Mike happened to buy a parcel of land where the colony was situated. He also had his ulterior motives and was looking to fold in the cache of an arts colony with his wellness enterprise. As for Burning Man, it’s a corporate entity. It’s a place with 60,000 people sharing a common ethos, each looking for self-expression, many of them dressed like extras for a sequel to Mad Max [1980]. I was both impressed and baffled that all the ‘freaks’ happened to look the same and sported a similar style. Burning Man was not my beach. I was there to work and I worked my ass off. But I don’t want to sound like I’m saying, ‘Oh, it was better back in my day.’ Probably older generations looking at mine thought the same, whilst I sometimes thought I was inventing the wheel or making the world a better place.

DF TV plays a big role in your work – in the game show that the spooks make Mike play in Secret Horror [1980], for instance, or Interstitial [1999], your note-perfect parody of public access TV and the downtown New York art scene of the 1980s.

MS For many years, when I was making video, I had a TV, but I didn’t have cable because I couldn’t afford it. On the rare occasions when I watched network TV, I’d get stuff that was in syndication, programmes that were older, years out of date. In a way, it echoed the Mike character – getting ideas, fashion and everything late. Public access seemed to be this kind of utopian space and artists talked about it as if it was this place they could inhabit and improve. Some did, but usually after 3am. Maybe I’m a little cynical, and it’s possible I’d be more positive if I actually had cable TV. I made Interstitial with Joshua White. We shot a lot of clips in one day at the same studio where many public access TV programmes were produced in the 1980s. It definitely helped to give Interstitial the look and feel of the period. I wore ridiculous wigs and horrible make-up, and artist friends would play the artist interviewees in the show. I gave them topics suitable to the period, such as the Tilted Arc public sculpture controversy or the representation of women in the Whitney Biennial or even President Reagan. The title, Interstitial, I just find it so funny. It’s one of those words that was bandied about in the art world 30 years ago and still crops up in art conversations today. I really liked that video. I was never big on improvisation, but almost the entire film is improvised. Some people think it is the funniest piece I’ve ever done.

DF I really enjoyed the segment featuring an artist called Zandra, who talks earnestly about making a performance piece called Flying, which evolved into Soaring. [Laughs]

MS Zandra was played by the artist Alix Pearlstein. She came in for the shoot with that kind of ‘artiste’ look. She was great. I think I requested she do that piece.

DF You once talked in an interview about ‘using TV to approximate TV’. Is this idea of approximation applicable to your work in general?

MS Yeah, that’s a good word to use. A work might have the look of TV, or an industry information film, but it’s not perfect; there’s always something a little off. In my early performances, I’d try to do some things with a certain degree of skill – like tap dancing or flipping forks and catching them in a hat or twirling a baton; nothing great, but just enough to show you that I could do it. It’s sort of an acknowledgement, a way of paying lip-service to how a prop functions.

DF So, approximation is also about the basic amount of information needed for us to recognize baton twirling or tap dancing?

MS Yeah, maybe those skills are amateurish, but my timing is usually pretty good, which adds some charm and pizzazz to what is really an ordinary performance.

DF Your timing is highly effective. I remember seeing the performance you did as Mike with the band Title TK, in which you stood off-stage, trying to phone up the band members to ask them whether or not you should bring your drum stool to the practice. None of them picks up the phone, and the audience just hears Mike’s internal monologue wondering over and over again why they won’t pick up the phone. It was painful and, at the same time, inexplicably funny. The performance had strong echoes of Andy Kaufman, with the repetitions, drawn-out pauses and awkward silences.

MS I modelled it after a famous joke by Danny Thomas called ‘The Jack Story’. He was Lebanese but worked the Borscht Belt circuit and people thought he was Jewish. The joke is that this guy is driving along in the pouring rain and he gets a flat tyre. He’s a mile away from the nearest gas station and he needs to get a jack. So, he starts walking to the gas station, and the whole time he’s thinking about getting the jack. He’s getting wetter and wetter, and brooding more and more about what the person is going to charge him for the jack. ‘What can they charge me? Five bucks? Ten bucks?’ After walking a mile in the rain, he’s working himself up into a state where he thinks the guy is going to charge him 50 bucks, and he’s so outraged that when he gets to the gas station and the guy asks, ‘Sir, may I help you?’ He says, ‘Yeah, take your fuckin’ jack and shove it up your ass!’ [Laughs] That’s the model for the performance with Title TK. It’s a slow, slow build.

DF When I saw your work in the exhibition ‘Rituals of Rented Island’ at the Whitney Museum last year, I had such a pleasurable experience watching your video Secret Horror. The scene in which the Mike character is singing ‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’ [1961] by The Kingston Trio, surrounded by dancing ghosts, had me giggling like an idiot. It made me very aware of how, within an art context, people can be allergic to the idea of entertainment or comedy, as if to admit to being entertained might undermine their identity as being critically minded. How do you relate to entertainment?

MS I like to be entertained. I also like being manipulated. It’s great when you can be transported by someone or something to some unknown place. Laughter can do that, and it can be pleasurable. It is a good emotion to have. In a way, I play a kind of clown or jester as a means to elicit laughter and to make comment or critique.

DF Comedy has run through art since the dadaists, but all too often it gets academicized. Critics and curators want to break the first rule of comedy; they want to explain the joke. In the same way that art ‘about’ sex is rarely sexy, artists who make work ‘about’ comedy are usually the least funny artists you can imagine.

MS Right, and there is only so much room for humour in art. Every three to four years they’ll have a humour show. ‘Strictly for Laughs’, ‘Not Just for Laughs’, ‘Laughing Matters’, you know – there’s a lot of them. I think I’ve been in a good five or six!

DF A big theme of yours is obsolescence. The artist Dan Graham once described your work as being about the ‘just past’. Mike arrives at things just when they’re on the way out, fading from view. What interests you about this?

MS It gives you distance. What I’m critiquing becomes clear; it’s dealing with something that’s already been assessed, evaluated and discarded – whether it’s a fashion or a TV show or an idea. And so you wonder why it’s been discarded. Is it because we need to make room for something else that is, basically, similar? It’s a way of illustrating how things work.

DF Mike illustrates what’s happening to all of us in the immediate present. You buy the latest iPhone; then, not so far down the line, you realize that everyone else has a new phone and yours looks dated. Even though it still functions perfectly well, you feel compelled to keep up with the crowd. This absurd process of consumer seduction is so close that we can’t see it, but Mike’s inability to catch up brings it into focus.

MS Right. The same things that drive us in the present happened in the past. My work allows people to get some distance from those impulses, because they can recognize those same drives in Mike.

DF Do you think this relates to the idea of fitting in versus being an outsider? Mike wants to fit in, but people don’t turn up to his parties, his business ventures seem doomed, he dances alone and is never as cool as the other artists on his TV show …

MS He’s constantly trying to fit in …

DF Is your work about loneliness?

MS Yeah, a lot of it. Mike’s just in this world of objects. It’s him and these objects and even when he’s around other people – in the disco-dancing piece, for instance, or as the host of Interstitial – ultimately he’s alone. Even Baby Ikki out in the street is alone. It probably has something to do with my interest in stand-up comedy.

DF Because it’s a lone, terrifying pursuit?

MS It’s to do with being alienated from what’s going on – from family and so on. A lot of comics are deeply depressed people. For me, it comes out of a lone studio practice. With performance you get an immediate response; you get to hear laughter and you know if something works or not.

DF Your work is frequently set in domestic environments – kitchens, living rooms. Mike is often seen doing household chores and your installation at ‘Rituals of Rented Island’ featured a baby-changing station for Ikki. Where does that interest come from?

MS It’s funny that you mention loneliness. In 1982, I did this audio piece called It Starts at Home about living alone with all these domestic appliances and wanting them to respond in some way. There’s a certain weight to these objects; they almost become characters. These appliances are useful, but we don’t just engage with them; they offer us hope and a comforting familiarity because they might have company some day. Something happens to us when we use them, but we never feel completely fulfilled by them, so we’re always left thinking, ‘Maybe it’ll be better with the next one.’

DF So, it’s also tied up with disappointment and self-improvement?

MS Perhaps. I’m interested in failure, and I’m also not very disciplined. So, the idea of self-improvement is difficult; it’s hard to stay on track and it’s very easy to fail – you can always move on to something else, to little things. Every year I make New Year’s resolutions. One year, I thought I should drink more fluids, but I didn’t. This year, I’m trying not to make as many sounds; you know, like sighs and moans for every physical movement – groaning whilst getting up out of chair or manifesting a feeling with a sound, whether it’s disgust, pain, impatience. I don’t need to vocalize everything. It’s like talking out loud. Maybe that’s like loneliness too, you have to put it out there so you can hear it, and then hopefully someone else will hear it. There’s a phrase that keeps coming back to me: when this friend’s father was wished a happy birthday, he responded: ‘It only gets worse.’

Michael Smith is based in New York, USA, and Austin, USA. In 2013, he had a solo show at Hales Gallery, London, UK, and participated in Performa 13, New York. This year, his work was included in 'Rituals of Rented Island' at the Whitney Museum, New York, and in Glasgow International, UK.