Pacific Standard Time

‘Pacific Standard Time’ is an collaboration that traces different histories of Southern Californian art from 1945 to 1980

‘Pacific Standard Time’ is an collaboration that traces different histories of Southern Californian art from 1945 to 1980

Sam Thorne

Associate editor of frieze, based in London, UK.

Sniping at the Getty’s activities is nothing new. As early as 1977, Joan Didion noted that, ‘From the beginning, the Getty was said to be vulgar […] ritually dismissed as “inauthentic”, although what “authentic” could mean in this context is hard to say.’ So, when ‘Pacific Standard Time’ (PST) – which was initiated and funded by the Getty Foundation – opened at the end of September, the reactions were fun to watch. Taking in around 70 cultural institutions in Southern California, PST is, as the Getty’s catalogue claims, ‘quite possibly the largest visual arts initiative ever’. Discounting New Deal-style programmes, this is surely the case; the collaboration, which runs for almost eight months and focuses on Southern Californian art produced between 1945 and 1980, has few precedents. But there was a derisive note to several of the early responses. Roberta Smith’s review in The New York Times was titled ‘A New Pin on the Art Map’, as though land had just been sighted by pith-helmeted art historians. Condescension was alloyed with the feeling that self-celebration on this scale is gauche or even paranoid – the kind of thing, as Dave Hickey opined, that Denver would do.

Other reactions saw PST as a brazen act of regional boosterism: city-myth production not so different from the antics of Los Angeles’s original boosters – those Downtown bureaucrats and PR men who ruthlessly promoted urban development early last century. But PST is better understood, I think, as recuperative rather than self-promoting, a long-due counterweight to the centrifugal pull of New York in accounts of postwar art in the US. Certainly this is how it was first imagined by the Getty Foundation and the Getty Research Institute in 2001, when the then-unnamed initiative had the relatively modest ambition of locating and preserving the historical record of LA’s art production. This was prompted by a dearth of scholarly books on the subject, made urgent by the fact that many of the artists who had come of age during World War II were growing old. By 2008, what began as an LA-focused archival endeavour had grown to encompass the whole of Southern California and, more dramatically, had developed an extensive exhibition component with a total budget of around US$10 million provided by the Getty. The initiative was to be led by the Getty, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA) and the Hammer Museum, but would take in dozens of smaller institutions and alternative, artist-led and commercial spaces.

At this point, any evaluation of PST will be partial in the extreme. This is not only because the programme is less than halfway through, but, with the enormous quantity of background scholarship and parallel publications, a clear sense of its impact is unlikely to be possible for some years. Such is the range and depth of material generated by the Getty’s investment, it’s even likely that our understanding of Southern Californian art will at some point be measured in pre- and post-PST terms. Less optimistically, this one-off cash injection provides a unique opportunity for those institutions which otherwise pay scant attention to marginalized artists to organize something they’d never usually get past the board.

The umbrella title – ‘Pacific Standard Time’ – insinuates a geographical zone that stretches from Vancouver and Seattle to Tijuana, but the focus is almost exclusively on Southern California, with no more than a smattering of Bay Area art. Few people, if any, will be able to see all of these exhibitions, which are clustered in and around LA, but framed by a triangle of outliers a couple of hours’ drive in each direction: down the coast to San Diego, north to Santa Barbara and as far inland as Palm Springs. Over the course of a week, I saw around 25 affiliated exhibitions. Aside from the flagship shows presented by the four lead institutions, these encompassed spaces as diverse as the Robert Venturi-designed Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MOCASD) and a middle school in Santa Monica, the tiny Craft and Folk Art Museum on Wilshire Boulevard and a lone mezzanine of the Natural History Museum. Exhibitions are intensely varied in approach, including surveys of movements and tendencies – Light & Space and ceramics, as well as Chicano, African-American and feminist artists – and focuses on individuals as diverse as Sam Maloof and Wallace Berman, Fred Eversley and Barbara T. Smith. Others trace the history of specific sites, such as the Watts Towers Art Center, Pomona College, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives. Whether a greatest-hits show, like the Getty Center’s flagship ‘Pacific Standard Time: Crosscurrents in L.A. Painting and Sculpture, 1950–1970’, or a tiny, gem-like archival offering such as ‘She Accepts the Proposition: Six Women Gallerists, 1967–1977’ at the Crossroads School, the shared 35-year period and SoCal vicinity links these island exhibitions into an archipelago.

PST is best understood as recuperative rather than self-promoting, a long-due counterweight to New York's centrifugal pull.

There have been a number of major museum surveys of LA art in the last two decades, most notably the Centre Pompidou’s 2006 ‘Los Angeles 1955–1985: Birth of an Art Capital’, which covered a similar period to PST. These exhibitions have tended to present the city as either the polar opposite of New York (a binary Robert Smithson and Nancy Holt were satirizing as early as 1969, in their video East Coast, West Coast), or as a culturally and geographically conflicted anomaly. Implicit in many prominent accounts of LA – from Bertolt Brecht through Reyner Banham to Mike Davis – is its double-status: heaven and hell; Utopia and dystopia. Binary exhibition premises, such as ‘Sunshine & Noir: Art in LA 1960–97’ (1997) at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, follow this line of thinking. They counter a caricatured – and persistent – criticism of LA art as unerringly breezy, the kind of interpretation exemplified by a 1970 Artforum review of ‘A Decade of California Color’ at Pace Gallery in New York, in which the critic complained: ‘It is apparently as easy to rack up in Los Angeles as an artist as it is to be a stringer of beads or an importer of herbals.’ More than any other city, art from LA is remarkably still often understood as a primarily localized phenomenon, conditioned by unblinking light, gleaming automobiles – ‘suggestions for colour on wheels’, John McCracken called them – and the lucky proximity to surf-shop resin experiments, craft movements, Hollywood and the aerospace industry.

Instead, PST visualizes a radically subdivided metropolis that makes such binary or localist readings impossible to sustain. For a long time, the narrative has been dominated by the gifted gang of young men – including Billy Al Bengston, Robert Irwin, Ken Price and Ed Ruscha – associated with Ferus Gallery (1957–66), and dubbed the ‘Cool School’ by Philip Leider, who edited Artforum when it was based in LA (Leider had originally wanted the magazine to be called Art West). But, travelling through the PST archipelago, stories become unavoidably more complex, as artists are encountered in wildly different scenes, guises and locales. For example, Bruce Nauman pops up in an exquisite survey of Light & Space at MOCASD as well as in the Orange County Museum of Art’s fascinating overview of conceptual art. Suddenly, the perceptual environments of James Turrell, Eric Orr and Doug Wheeler don’t seem so far removed from the early process-based sculpture of Nauman, Paul McCarthy or Wolfgang Stoerchle, or even from Michael Asher’s first installations. Often-overlooked communities are also well represented: for example, Asco, the Chicano activist art group are given their first retrospective (which is reviewed on page 154 of this issue), while the Hammer has organized ‘Now Dig This!’, a superlative survey of African-American art. The markers that I’d previously used, as only an occasional visitor to LA, to navigate art in the city – Wallace Berman’s obscenity charge in 1957 or the Watts Riots of 1965; John Baldessari cremating his paintings in 1970 or Bas Jan Ader being lost at sea in 1975 – started to become unmoored. If PST has a canonizing impulse, as has been claimed, then it has surely failed. What emerges is so messy and irresolute that the well-told narratives and familiar categories start to break down.

What emerges is so messy and irresolute that the well-told narratives start to break down.

But the framing of PST also reinforces some of the art-historical orthodoxies it is attempting to dispute. ‘Art since 1945’ has been a standard periodization since the 1950s, though I wonder about its particular relevancy to LA. All but a few of the exhibitions in PST feel reluctant to acknowledge the first third of the 35-year period that it has set itself, and none of the key presentations from the four lead institutions touch the art of the ’40s (only the Getty Center’s show strays earlier than 1960). It may be that the main activity in that decade was in the Bay Area rather than in Southern California, and LA’s cultural infrastructure was certainly slow to develop: the Dwan and Ferus galleries didn’t open until towards the end of the ’50s, while the art museums either opened later or – like actor and collector Vincent Price’s Modern Institute of Art in Beverly Hills (1948–9) – were short-lived. In any case, the consistent focus of most exhibitions under the PST umbrella is not 1945–80, but rather the 1960s through to the early ’70s.

One major exhibition – both the biggest and, reputedly, the most expensive that PST has to offer – that does deal with the late ’70s is ‘Under the Big Black Sun’ at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. The show – which is bracketed by Richard Nixon’s resignation and Ronald Reagan’s ascension – includes masses of extraordinary work, though, in its evocation of a vibrant artistic pluralism, it is exhausting as well as enlightening. Highlights for me included early work by Jeffrey Vallance and Christopher Williams, documentation of performances by Suzanne Lacy and Lynn Hershman, and little-known series by John Divola and Robert Heinecken. The crux of curator Paul Schimmel’s catalogue essay is that the pluralism which ‘cohered as Postmodernism during the 1980s in New York effectively codified ideas and concepts made in California between 1974 and 1981’. To claim this period as a forerunner in any theoretical sense must overlook both European critical theory and New York’s own fertile scene. It’s a claim that doesn’t need to be made. But it is perhaps revealing of how acutely felt the decamping was of the so-called CalArts Mafia – former students of Baldessari, including Jack Goldstein, Matt Mullican and David Salle – from LA to New York in the mid-’70s. This collective move to the East Coast – Douglas Eklund once called it a ‘mass migration’ – marks the diminuendo of one strand of PST. Like museums everywhere, institutions in LA are being forced to broker increasingly Faustian pacts with collectors and corporations, but there is surely hope to be gleaned from a collaboration of this scale. For now, whether PST is regionalist, localist or even boosterist may not matter so much. The more pressing issue is how the research and exhibitions that it has produced can be developed. From wherever you’re sitting, its impact is going to be interesting to watch.

Stacey Allan

Executive editor of East of Borneo, a collaborative online art magazine of contemporary art and its history as seen from Los Angeles. She is based in Los Angeles, USA.

Sometime last year, I came across an interview with the nouvelle vague filmmaker Agnes Varda that touched on her time in California in the late 1960s. The reporter writes that Varda is sometimes reproached for missing the events of May ’68 in Paris. She was, at that time, living in Los Angeles with her husband, Jacques Demy, as he directed his first American feature film. When Varda was asked about regrets, I was moved by her elegant and unapologetic response: ‘[In California] we had flower children, we had love-ins and sit-ins and huge free concerts. What we found was a real desire for brotherhood that was magnificent, that wasn’t just about making demands. I wasn’t [in Paris], that’s all there is to it – but I saw things they didn’t see.'

My own sense of ‘Pacific Standard Time’ is that it is best taken as something along these lines: a simple statement of fact that we, in Los Angeles, saw things that others didn’t see. We had Wallace Berman, Womanhouse (an installation/performance space organized by Judy Chicago and Miriam Shapiro in 1972) and plastics. We had the 1965 riots in Watts and we had Wet (1976–81), ‘a magazine of gourmet bathing’. Some outside criticism of the project has framed it competitively, as overcompensation by a city that, compared to New York, has historically been the underdog. But to frame it in this way is to be out of step with a looser local objective: to open up new perspectives that complicate the idea of a singular US art history.

Like Los Angeles itself, far fewer people will experience 'Pacific Standard Time' than will read about it.

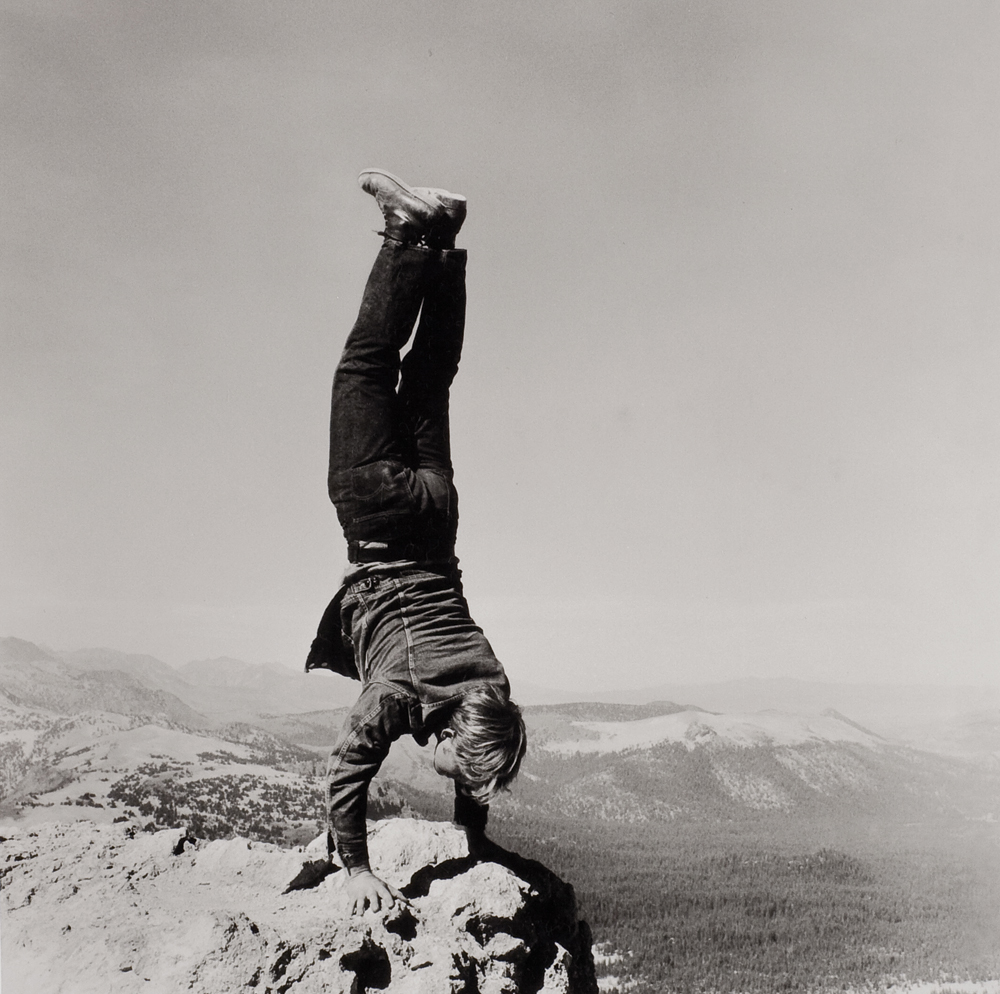

The lack of critical attention focused on LA has been much discussed as something that has positively shaped – and to some degree continues to shape – artistic developments here, affording greater experimentation with less fear of high-visibility failure. It also means that the successes, if viewed in this binary way, have been largely unrecorded. Take the work of Senga Nengudi, for instance, who is included in the Hammer Museum’s exhibition ‘Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980’. Nengudi, working with the collaborative group Studio Z (which included David Hammons, Maren Hassinger, Barbara McCullough, Ulysses Jenkins and others), staged and documented Ceremony for Freeway Fets (1978) – a largely improvised performance ritual with music and costumes – on an ignored patch of land under a freeway overpass. Nengudi used space, but not in the ‘Light & Space’ sense of the word.

One of the great things about LA’s sprawling geography is that it reinforces the feeling that nobody is looking, either literally or critically speaking. For Asco, a Chicano collective comprising a small group of friends from East LA, that invisibility both enabled and inspired theatrical street performances that were later promoted and distributed as ‘No-movies’ – essentially film stills for non-existent Chicano films, starring themselves. If invisible to the culture industry, though, they were certainly not invisible to law enforcement. Many of their works carry the sense of being undertaken quickly while no one was looking. First Supper (After a Major Riot) (1974) took place on a traffic island on Whittier Boulevard in East LA, not long after the Chicano moratorium, when the area was still heavily policed.

There has been some outside debate around PST’s geographical focus on Southern California – rather than encompassing, for instance, the entirety of San Francisco and the Bay Area. But despite the fact that many artists travelled and even lived for a time in both regions – most famously Berman, George Herms and those associated with the Beats – the two have distinct histories. One has to remember that San Francisco is some distance from LA: criticizing the localism of PST is a little like observing that a show about New York doesn’t cover Buffalo. The regionalism of California, one of the largest states in a country the size of the US, is not a great deal different to the regionalism one can find in, for instance, Western Europe.

Regionalism even exists within the city of Los Angeles itself, and this can be felt in the historical positioning of the various institutions involved. One truth about LA is that there has never been one ‘LA art scene’, but many. Artists communities now seem to be organized less geographically than academically: it is not a city where someone might describe themselves as, say, ‘an artist from Topanga’ or ‘an artist from Venice’, so much as whether they went to UCLA or CalArts or Art Center, and who they studied with. While PST may not leave a lasting legacy in terms of more inclusive exhibition programming in the city, my sense is that a lot will change at an academic level in terms of the diversity of scholarship that happens afterwards. As a result, there will hopefully be more access to, and perhaps more pride in, LA’s rich past as it impacts its present and future.

It was recently reported that of the more than 60 exhibitions that have been organized, few will travel and none will travel to New York. Sharon Mizota of the The Los Angeles Times has set about the task of seeing all the exhibitions – which is ambitious and admirable – but even most people here in the city won’t be able to see everything, and so much of the show has been mediated through print, through people’s words and perspectives. Like Los Angeles itself, far fewer people will experience PST than will read about it. In the aftermath of PST, a key part of the show’s legacy – after the billboards and advertisements have disappeared – will be the publications and the availability of new research material.