A Personal Latin America

Curator Fernanda Brenner and artists Mario García Torres, Carlos Motta and Amalia Pica discuss what Latin American art means to them

Curator Fernanda Brenner and artists Mario García Torres, Carlos Motta and Amalia Pica discuss what Latin American art means to them

In the 25 years since frieze began, contemporary art from Latin America has undergone profound changes. The global expansion of the art world has been reflected in the growth of the gallery and museum scenes in the region. As information about the histories of Latin America has spread via the internet, dominant art-historical narratives from Europe and North America have been reshaped. Yet, it is a vast continent, stretching from Tierra del Fuego in the south to Punta Gallinas in the north. ‘There are thousands of Latin Americas,’ writes artist Mario Garcia Torres, each of them subject to the social and political weather patterns of individual countries and to conversations between artists, writers and curators at a local level. With that in mind, we asked four people — curator Fernanda Brenner (Brazil), and artists Garcia Torres (Mexico), Carlos Motta (Colombia) and Amalia Pica (Argentina) — for their take on what Latin American art means to them and their region.

Carlos Motta

Carlos Motta is a multi-disciplinary artist based in New York, USA. Recent and upcoming solo exhibitions in 2016 include: Mercer Union, Toronto, Canada; PPOW Gallery, New York, USA; Pérez Art Museum, Miami, USA; Hordaland Kunstsenter, Bergen, Norway; and MALBA, Buenos Aires, Argentina. He will also participate in the 32nd Bienal de São Paulo, Brazil, in 2016.

On 23 June 2016, the Colombian government held a ceremony in Havana, Cuba, to announce a peace accord with FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), purportedly ending the devastating six-decade armed struggle that has permeated every aspect of Colombian society. Colombian contemporary art has broadly addressed the war, producing works that reflect on the countless consequences of the conflict: the displacement of populations, the loss of human dignity and life, the prevalence of conservative social politics and episodic attempts to memorialize the victims. It has also engaged with issues of class, as well as racial and (more rarely) gender and sexual inequalities.

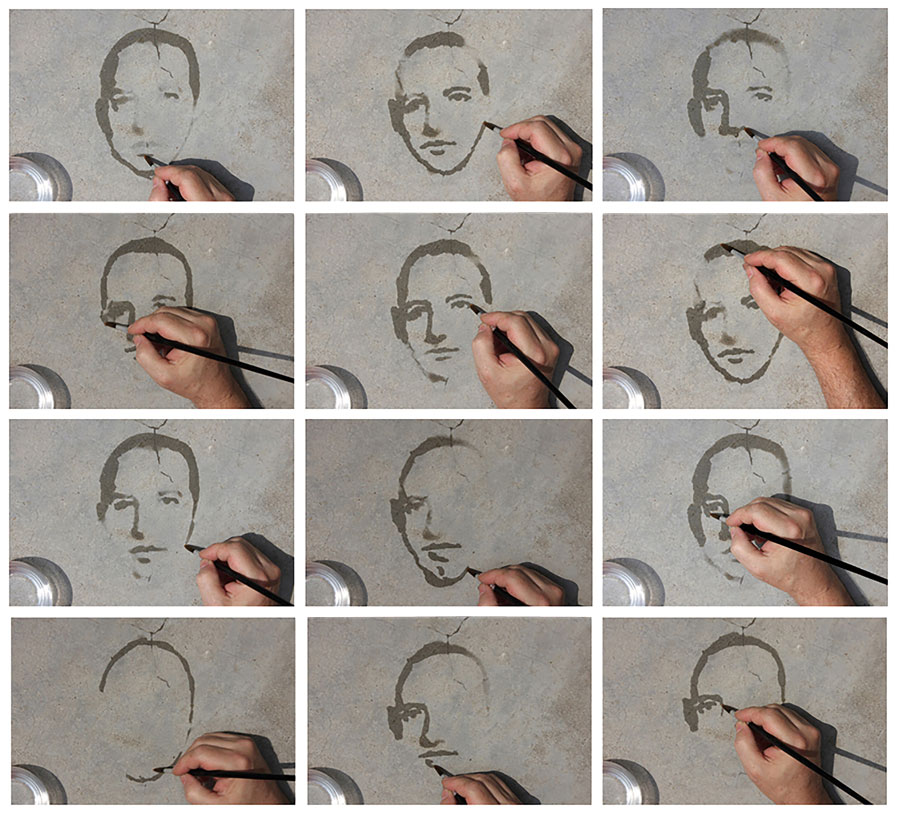

Although a generation of artists – including Eduardo Ramírez Villamizar, Omar Rayo and Fanny Sanín – produced distinctive formal approaches to modernist painting and sculpture, it could be argued that Colombian artists have resisted distancing their work from the country’s social and political violence and have, instead, sought ways to critically reflect upon it. Important artists, such as Débora Arango, Beatriz González, Oscar Muñoz, José Alejandro Restrepo, Miguel Ángel Rojas and Doris Salcedo developed poignant practices that defined the character of Colombian art as politically charged. For example, Arango’s expressive figurative paintings depict the years of la Violencia (the Violence, 1948–58), a period of civil war between the liberal and conservative parties that is often considered to have initiated the subsequent decades of unrest, while Salcedo’s La casa viuda (The Widow’s House, 1992–94) is a tribute to rural displaced women. From Restrepo’s Musa paradisíaca (1993–96), an excruciating video installation about massacres in banana plantations, through Muñoz’s haunting Proyecto para un memorial (Project for a Memorial, 2004–05), a series of video projections in which a hand attempts to paint portraits with water onto a concrete surface that rapidly dries, erasing all traces of the person depicted, to Rojas’s affecting and suggestively homoerotic David (2005), a series of full body portraits of a mutilated Colombian soldier posing as Michelangelo’s famed sculpture: artists in Colombia have chronicled the war and its effects both literally and allegorically.

As an artist who grew up during the 1980s and ’90s – arguably the most violent decades of the country’s recent history – and who began producing work during the 2000s, I looked up to these artists as role models and was interested in the ways in which they demonstrated a commitment to the representation of the political. In my own work, I have inquired about the role of art as a tool for social change and have wondered whether or not a sense of political responsibility to one’s socio-political and geographic context is empowering, limiting or even crippling when developing an artistic language. I have also asked myself: what should the role of art be in times of conflict? Should artistic expression reflect on the realities of war? How do these imperatives affect other forms of artistic production and, thus, the varieties of artistic growth in a country?

Over the last 15 years, Colombia has undergone a major shift in both its internal situation and international perception – from a war-torn, drug-producing country to a tourist destination that attracts foreign investors. In parallel to this shift, the international art world and market set their eyes on Colombia, strengthening its museums and independent spaces, its art fairs and collectors, and the visibility of its artists and the diversity of their practices. While myself and many of my colleagues – including Felipe Arturo, Milena Bonilla, Carolina Caycedo, Wilson Díaz and Ana María Millán – continuously engage with the socio-political realities of the present, artists such as María José Arjona, Iván Argote, Pedro Gómez-Egaña, Mateo López, Nicolás Paris and Gabriel Sierra have gained extensive international recognition with practices that investigate a wide range of conceptual and formal issues, mostly unrelated to Colombian identity or politics.

During the militaristic political regime that transformed the country through war, and the implementation of a neoliberal economic model under President Álvaro Uribe (2002–10), an opening for social and cultural progress appeared that was paradoxical and certainly unintended. I see this growth in the recognition of different kinds of research, artistic languages and form both inside and outside of the country: a freeing effect that has rendered the stereotypes associated with Colombian artistic production irrelevant. Today, the country boasts a wide range of artists that have the choice to engage with our histories of violence, or not.

I do not believe that art is inherently political, contrary to the frequently stated cliché. But some art may disrupt hegemonic historical narratives and processes of political and social oppression. The best contemporary Colombian art has provided forms to relinquish the pressure of war and, in spite of its fog, produced counter narratives of resistance and freedom.

Amalia Pica

Amalia Pica lives in London, UK. Her work is currently included in the new Tate Modern collection display in London, at Manifesta 11 in Zurich, Switzerland (11 June – 18 September), in ‘Under the Same Sun: Art from Latin America Today’ at South London Gallery (10 June – 4 September), and in the Gwangju Biennale, South Korea (2 September – 6 November). This autumn, she will have solo exhibitions at Kunstverein Freiburg, Germany, and Marc Foxx Gallery, Los Angeles, USA.

Every day, on my way to the National School of Fine Arts Prilidiano Pueyrredón in Buenos Aires, in the late 1990s, I walked passed Belleza y Felicidad (Beauty and Happiness). It was a project space started by Fernanda Laguna where art was being made with felt-tip pens, coloured card and tampons. I found the modesty of means confusing, but the sense that not much was needed in order to make art was hard to resist.

While in class, the process of resisting the absorption of the art school into the newly created Instituto Universitario Nacional del Arte led us to occupy the school for several weeks. It was hard to predict that the groups which then supported some of our demos (such as Grupo de Arte Callejero [Street Art Group]) would end up as part of the international art world, as their activities maybe didn’t seem enough like art.

The end of the 1990s was perceived by many as an era of ornamental abstraction in the hands of artists such as Jorge Gumier Maier and his Grupo del Rojas (Rojas Group). As much as there was a political side to materiality, the imagination and the queer, to a confused art student these tendencies seemed to be removed from bigger issues which led to the economic crisis at the beginning of the new millennium. (I finished art school in 2001, on the day the country’s economy collapsed.) Yet Ana Longoni, the art historian of the Left, was, at the time, building an archive documenting the interventions and actions of artists and collectives who had spoken out against the recent dictatorship and were dealing with its aftermath.

In the 2000s, distinctions between formal and politically engaged art were no longer so black and white. Abstract painter Magdalena Jitrik was also a founding member of the Taller Popular de Serigrafia (People’s Screen-Printing Workshop), an artist collective that lent images to workers’ protests: they would stamp the T-shirts of attendees in demonstrations and worked in collaboration with textile factories that had been recuperated by workers co-operatives.

‘What should the role of art be in times of conflict? Should artistic expression reflect on the realities of war?’ Carlos Motta

We had access to international information, although mostly I remember hearing a lot about the Bienal de São Paulo (Brazil was always a reference) and reading a Spanish art magazine called Lápiz (Pencil). With the expansion of the internet, international information became much more easily available but it also provided a way to connect different places within Argentina. Buenos Aires, like many big cities, has always been a bit bossy with regards to the rest of the country and the first half of the 2000s saw this start to change in a big way. TRAMA was a five-year artistic and educational initiative that played a major role in the federalization of the art scene. They organized workshops with local artists in cities such as Tucumán and hosted artists and tutors from both Buenos Aires and abroad. The internet also enabled artists to take part in the art world without having to move their studios to Buenos Aires. (For instance, Adrián Villar Rojas, who represented Argentina at the Venice Biennale in 2011, has a studio in Rosario.)

An interest in local politics has also developed hand-in-hand with the much greater participation of Argentinian artists in international biennials and fairs.

Whereas, in the past, historians and artists tended to direct institutions, curators educated abroad now return to Argentina to take on these posts: Victoria Noorthoon at the Museum of Modern Art Buenos Aires, for instance, or Ines Katzenstein, who is in charge of the Universidad Torcuato di Tella. Important private museums, such as the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, have opened with high attendance numbers and popular exhibitions. The oldest art fair in Latin America, Arte BA, which also turned 25 this year, has an international outlook and has become a major event in the calendar. In this sense, Argentina is no different to other places. The independent Argie spirit has also made its mark with projects such as El Basilisco, an international residency programme based in Avellaneda, a neighbourhood just south of Buenos Aires, and La Ene, also in the capital, which is both a residency and an experimental contemporary art museum.

I left Argentina 12 years ago, but have followed the country’s development both through sporadic visits and online. It remains a place where wonderful art is being produced and exhibited in institutions that are becoming more solid. But the working conditions of artists are still precarious: production expenses and artist fees are unheard of, and many curators and artists continue to have to draw on very limited resources in order to make things possible in a country that is very far south, even by South American standards.

Fernanda Brenner

Fernanda Brenner is the founder and Artistic Director of Pivô, an independent, non-profit art space in São Paulo. Since 2012, the space has hosted around 40 projects, including exhibitions, site-specific works, artist residencies and a studio programme, featuring more than 200 artists from 15 different countries. Brenner recently curated the show ‘So Far So Good’ as part of White Cube’s ‘Inside the White Cube’ programme.

I was born in Brazil in the 1980s, an era of economic stagnation marked by the end of 21 years of military dictatorship. In this unstable albeit optimistic context, Brazil’s small art scene started to take a different shape.

Swept up in the excitement of political change, a new way of thinking about cultural policy began to emerge. In 1985, the Ministry of Culture was founded as the art market started to gain momentum, timidly expanding its network of collectors and establishing an international presence, resulting in more public exposure to the visual arts. However, this era of optimism didn’t last long as the cultural sector was once again wrecked by the disastrous government of President Fernando Collor de Mello, and only began picking up at the start of the 2000s.

In order to understand the Brazilian cultural scene, we must take into account its resilience and its contradictions. National cultural policies seem to revolve around three axes: neglect, authoritarianism and instability. Whilst the institutional context has been a direct victim of this perverse discontinuity, the art market has found other solutions to keep pace. In my attempt to loosely map the complex context of the visual arts scene in Brazil in recent decades, two landmark events immediately come to mind: Walter Zanini’s role as director of the University of São Paulo Museum of Contemporary Art, between 1963 and 1978, and the 24th Bienal de São Paulo curated by Paulo Herkenhoff in 1998.

‘It didn't take long for it to become clear to me that the concept of a Latin America confined to geographical limits was a fiction; it was a subjective mother-tongue that existed in several places.’ Mario Garcia Torres

Zanini was one of the first to question Brazil’s institutional scene. He directed a museum that, in his own words, ‘no longer entered the scene after the artwork but was concomitant to it’, shifting the focus from the collectable object to the artistic process. Almost 20 years later, Herkenhoff also changed curatorial thinking in Brazil. His Bienal de São Paulo re-examined Brazilian culture in relation to the West, inverting a pervasive logic inherited from colonialism, whereby the country has stronger ties with Europe and the US than with the rest of Latin America.

The early years of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s government and its economic optimism re-invigorated the local art scene with an energy similar to that of the 1980s. Despite the global economic crisis, Brazil enjoyed a period of significant growth in the early 2000s, followed by the exponential expansion of the visual arts market and public interest. 2005 provided the ideal environment for SP Arte, the first art fair in São Paulo:

a budding internal market driven almost exclusively by local production; a new generation of art galleries; and growing international interest, evidenced by the presence of Brazilian artists at the Venice Biennale in 2001 and 2003. In 2006, Bernardo Paz turned his gigantic art collection into a public park, Inhotim: an unprecedented initiative showcasing the potential of Brazilian collections. A more balanced and healthier art scene saw the launch of a series of autonomous platforms for the production and dissemination of the arts, including specialized magazines and publishers, artist-run initiatives, independent institutions and private collections open to the public.

Nowadays, people say ‘art is the new thing’ and I hear this with a mixture of sympathy and scepticism. On one hand, the proliferation of interest in contemporary art and a new public is fundamental; however, on the other hand, the structures necessary to ensure its consistency and development are absolutely unstable, particularly in the current complex political and economic conditions following the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff. The lack of continuity and the tendency to support spectacular events instead of investing in cultural infrastructure are the biggest challenges to the development of an art scene in which the only constant is the quality of its artists.

Mario Garcia Torres

Mario Garcia Torres is an artist living in Mexico City, Mexico. He will co-curate, with Magali Arriola, a performance programme at ArtBo, Bogotá, from 27–30 October.

There are thousands of Latin Americas. When an overarching concept such as ‘Latin America’ is imposed on people’s daily life, they are pushed into replicating it in a personal way. One version I discovered early on in my career in the arts was largely defined by the exhibition ‘Re-Aligning Vision – Alternative Currents in South American Drawing’, at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo in Monterrey, where I was living in 1998. The exhibition widened the perspective I had on conceptually oriented practices. The artists included in the show offered a framework I could use to negotiate my own desires and intentions.

Until then, the region conventionally defined by the southern border of the US and the tip of Argentina could be perceived as a vast archipelago that one had to piece together – at least in terms of the visual arts. Literature and pop culture, on the other hand, felt easier to grasp. Over the decades, writers such as Mario Vargas Llosa and Jorge Luis Borges, or musicians like El General and Tito Puente, had managed to create a common ground that influenced other authors and performers all around the region. Not so in the art world. With only a dial-up internet connection available in the north of Mexico, that type of artistic discourse was simply not accessible to me.

‘Re-Aligning Vision’ was conceived during a global revisionist moment that shone light on many overlooked practices from the 1960s and ’70s. And, like elsewhere in the world, the recirculation of those works greatly influenced the practices of those of us who started working during the first decade of the 21st century. We didn’t know about art made decades before in the region, but we could listen to the Argentinian band Virus, which included lyrics by artists Roberto Jacoby and Eduardo Costa, and early versions of now world-famous reggaetón songs such as El General’s No me trates de engañar (Don’t Try To Fool Me, 1991) had being blasting around for sometime.

It didn’t take long for it to become clear to me that the concept of a Latin America confined to geographical limits was a fiction; it was a subjective mother tongue that existed in several places. By the early 2000s, when I first met Luis Camnitzer and David Lamelas, two key figures in the development of conceptually-oriented practices from the region, it felt that Latin America had expanded into the US and Europe where those artists had developed their careers, that Latin America existed somewhere else.

Later, when I met Rafael Ferrer, a Puerto Rican musician-cum-artist who had played an important role in the process art movement in New York, information was travelling faster and sharing had become a priority for artists. The internet had helped to bypass the fragility of local institutions and unprofessional government agencies. Over the past 15 years, the region’s old, anachronistic biennials have been slowly taken over by a younger generation of art professionals and its art fairs have become more established. Artists who didn’t relocate outside the region managed to open up the local scenes to an international dialogue.

During that transformation, blogs such as Pablo León de la Barra’s ‘Centre for the Aesthetic Revolution’, to mention just one example, played an important role in creating a multi-layered platform through which art from the region was circulated unfiltered, eventually creating a real exchange: a world in which Los Super Elegantes’ funk carioca performances could co-exist with Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla’s installation Puerto Rican Light (2015). It was, for me, an important moment; the early examples of radical practices had been consciously transformed and the Latin American archipelago had revealed itself as a mass of land, where thousands of ideas influenced each other.

Like a cumbia song that had travelled fast and been adopted and transformed multiple times along the way, it felt that those many Latin Americas could finally share the same rhythm and, for a moment, synch themselves.