Peter Hujar

Maureen Paley, London, UK

Maureen Paley, London, UK

A few years ago, I had the good fortune to find myself with an afternoon to kill in Palermo, Sicily. Though the city was bathed in bright light that day, I felt compelled to seek out one of its murkier attractions. The Capuchin Catacombs are a network of burial passages beneath Palermo’s Capuchin monastery. Between 1599 and 1880 around 8,000 bodies were interned there. It’s an extraordinarily morbid place, bearable only due to the welcome distraction of an endless flow of visitors who, like me that afternoon, purchase a €3 entry ticket to descend into the rayless tomb for a glimpse at its skeletal bestiary.

For my prior knowledge of this remarkable place, I had the late American photographer Peter Hujar to thank. More precisely, a single image of Hujar’s – Thek in the Palermo Catacombs (II) (1963) – a portrait of his lover and fellow artist Paul Thek. In this photograph, a willowy and handsome Thek appears just to the right of frame. He’s leaning back, arms folded – his pout issuing a soupçon of libidinous suggestion. But sex is just the image’s foil. All around, skeletons gather. Though not included in Hujar’s third posthumous exhibition at Maureen Paley, this single image – its grim vitality – can be read as symptomatic of the photographer’s output at large. For Hujar, death was always looming.

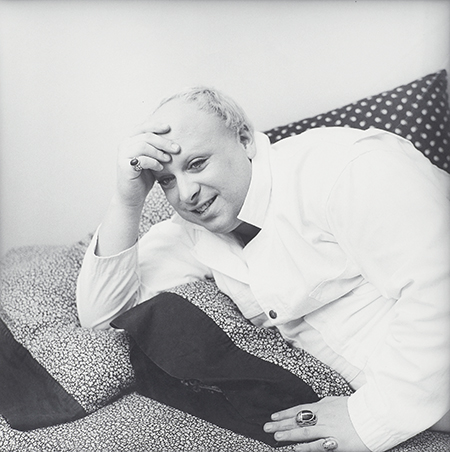

A fashion photographer in the 1950s and ’60s, by the early ’70s Hujar began to move in the avant-garde circles of Manhattan’s Lower East Side. He soon left fashion behind, though not without retaining in his artwork the formality of studio photography. Shot in black and white with a twin-lens reflex camera, Hujar’s photos are rich in tone, warm in contrast and mostly, as is the case with the 12 vintage silver gelatin prints in this exhibition, focused simply on sitting or reclining subjects.

In the introduction to Portraits in Life and Death (1976), the only book of Hujar’s work published in his short lifetime, writer and close friend Susan Sontag suggested that, in the way they ‘sit, slouch, mostly lie’, Hujar’s subjects appear to ‘meditate on their own mortality’.

Sontag’s saturnine description came across clearly as I moved along the stuttering line of uniformly square prints installed along three walls of the gallery’s downstairs space. Sitters appear emptied of pretence, radically alone in the world yet somehow ok. Even when not literally on their own, as in the case of Merce Cunningham and John Cage Seated (II) (1986), there remains something divinely empty in the way they just sit there. In William Burroughs (II) (1975) the beat author, sat in a low chair, offers a starkly unmoved pose straight to camera. Yet the curio here – and Hujar knows it – is Burroughs’s exotically trimmed waistcoat. ‘This man has seen things,’ the garment says. ‘Perhaps more than you or I ever will.’

Other less celestial, but no less cosmic, doyens of the American avant-garde also feature. John Waters’s principal muse, Divine, is pictured out of drag, falling forward onto a pillowed chaise longue, (Divine II, 1975) while Jackie Curtis, the star of Andy Warhol’s Flesh (1968) and Women in Revolt (1971), appears stone dead, laid to rest in an open coffin (Jackie Curtis Dead, 1985).

This last image suggests a shift in register, one significant for this exhibition as well as for the ongoing legacy (and continued revival) of Hujar’s work. For here it’s not – as suggested by Sontag – the sitter that contemplates mortality but, rather, mortality that’s contemplating the viewer.

Moving between photographs, I searched Wikipedia on my phone. Out of the 12 subjects captured by Hujar between 1958 and 1986, the New York-based music journalist and photography critic Vince Aletti is the only one still alive. The others, like Curtis back in ’85, now rest in peace (many having suffered premature deaths through illness, suicide or overdose).

Hujar himself, like his fellow Palermo adventurer Thek, succumbed to AIDS-related illness in the late 1980s, part of a generation of New York artists laid waste by the deleterious virus. Death is everywhere; time, illness and incident underwriting and expanding the grave portent of Sontag’s original reading of this work.