‘Photography Makes Me Look Within’: a Tribute to Laura Aguilar (1959–2018)

Remembering the photographer’s invaluable contribution to the history of queer aesthetics

Remembering the photographer’s invaluable contribution to the history of queer aesthetics

‘most of all, photography makes me look within’

At her 2015 talk at Cal Arts about her work, Laura Aguilar credited her cousins with being her first photographic subjects. The picture Cousins at Disneyland (1978) is of her family, smiling and being happy and in the talk she attributes learning how to be a photographer to learning how to photograph them. Her brother taught her how to develop film. Here was an artistic practice that emerged out of compassion and kinship and those two themes cut across Aguilar’s copious work. In her Cal Arts talk video from 2015, she opens with the biographical, showing how important that was to her work. For Aguilar the biographical was political – her family was from the San Gabriel Valley, of Chicanx and Latinx heritage – and radiated outwards. Her profound and probing work grappled with what it meant to be queer in a Latinx and Chicanx community and how that community is portrayed and also absented from dominant depictions of the queer community in Los Angeles. What does it mean to share community, to share intimacies, to forge relationships? Even more outward than these questions, what does it mean to share ground and Earth?

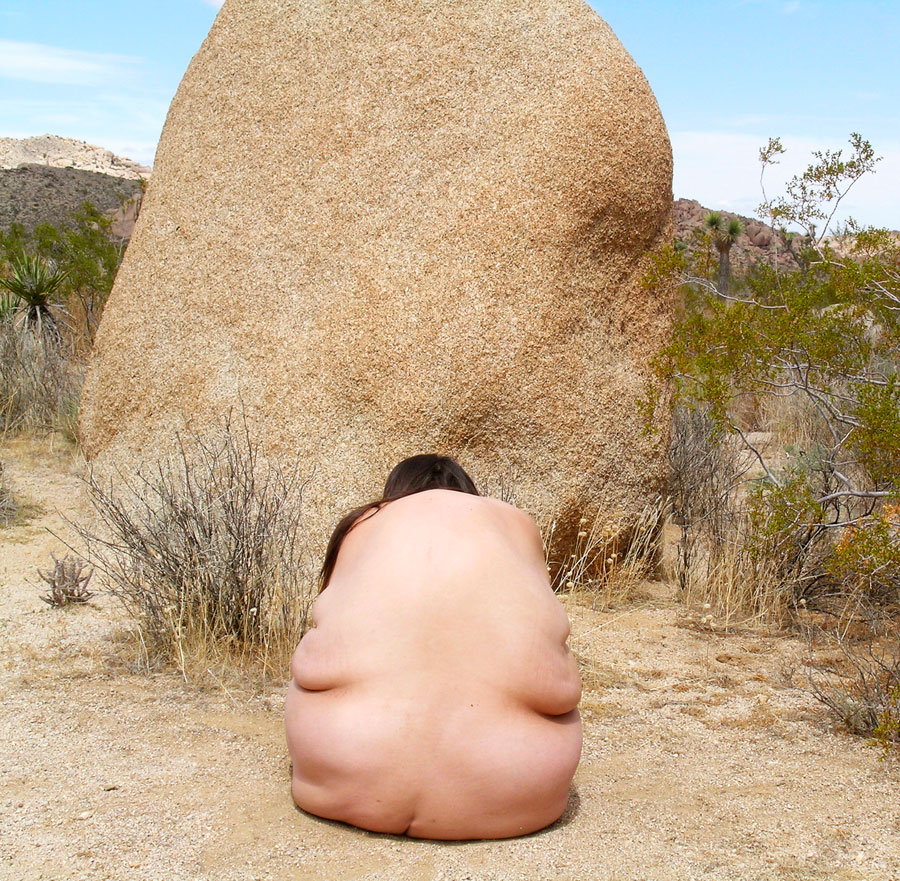

Some of Aguilar’s most famous works aren’t about queer sociality and representation but rather, what queer brown and Black and fat embodiment does to shift, gently and powerfully like an undercurrent, how we think about the parameters of the natural and unnatural, subject and object, human and non-human. This work is an actual queer materialism through photography. Aguilar creates another landscape and ecology. She turned Joshua Tree National Monument into a queer and decolonial topography. The work is compelling; in a rather subtle way Grounded #114 (2006) queers the natural. In the image she relinquishes the coordinates of the Human as subject and instead becomes another flourishing of the Earth’s ecological immanence. What is considered aesthetically trespassing and transgressing – the brown and fat queer body – is now given ground: situated. The ground is lateral, horizontal: a landscape. A continuum of animacy is revealed in the landscape she creates in the photograph: a stone boulder resembles embodied flesh. Rather than positioning herself in the photograph as a Subject that sovereignly transcends and rules nature around her, Aguilar instead opts for dis-individuation and de-subjectification. She situates her body within a general ecological field. Her face is turned away from the camera; she blends in with the setting. Body becomes boulder. Here it is not the Human we are confronted with but ecological entanglement. The aesthetic of the settler is quite literally, to borrow from Frantz Fanon, ‘put out of the picture.’ This is not done through an iconography of political violence, rather it is almost like a subliminal shift of focus of her lens.

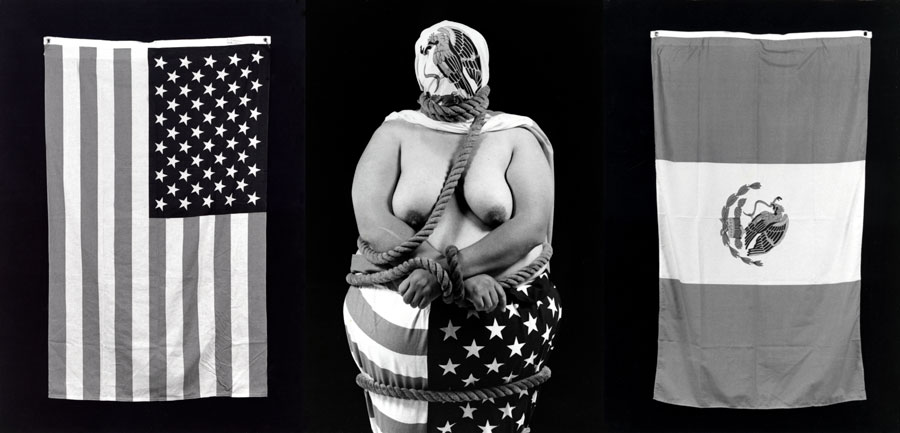

Aguilar constantly furnished her body as the site of political intervention, into the nation state, with its securitizing apparatuses – Three Eagles Flying (1990) stages this critique of American imperialism and borders while also making an immanent critique of the Mexican state and, especially, of sovereignty itself. Her work Motion #56 (1999) turns stationary bodies into a cascade. Again the face is partially concealed, not in antagonistic defiance but as a covering – her hair obscuring her face, in an act of subtle refusal of the gaze. Aguilar’s self-portraiture remains so powerful in the ways that it inverts and queers the given, turning it into elsewhere and de-materializing the self so that there is a mimeticism with the environment and surroundings.

In Invisible Man (1952) Ralph Ellison wrote about the phantasmic and spectral nature of being looked through and invisibilized – the absented presence of the anti-black gaze that denies interiority to Black personhood. Aguilar’s work both dramatizes the invisibilization – ‘we are present, but remain unseen’ – that accompanies the colonial gaze and problematizes perception itself. As we don’t know what to make of her situation in the New Mexican desert, it moves away from a focus on the singular self and foregrounds the materiality of the body. What is left is a queer liminality that presses at the limit and threshold of the boundaries between the mind and the body, self and bodily substance. Aguilar communed with queer Latina women, centering their sociality but even more than that, co-creating it. ‘My work is a collaboration between the sitters and myself.’ She created a queer Latina aesthetic vernacular that she felt was missing from the dominant discourse of queer LA communities.

Aguilar’s work offers us a wonderful and beautiful gift. She helps us think about the queer aesthetics of relation and entanglement, from the relation and entanglement between queer Latinx and Chicanx communities in East Los Angeles, moving outward to the sphere of the globe and the queer relation that blurs the distinction between rock and body. Passing on 25 April, she will be dearly missed and dearly mourned. Yet the queer aesthetic intimacies and inquiries that she gifted us with and through her lens as a photographer live on in her work for us to explore and pass on.

Main image: Laura Aguilar, In Sandy's Room (detail), 1989, silver gelatin print, 1.1 x 1.3 m. Courtesy: the artist and the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center © the artist