Phyllis Bramson

Carl Hammer Gallery, Chicago, USA

Carl Hammer Gallery, Chicago, USA

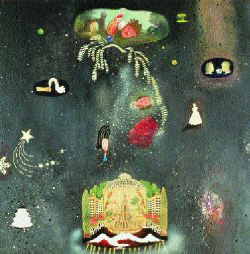

Phyllis Bramson's paintings are coy affairs - girls languish, swans circle slowly, and bold little animals pout and dance in quirky snippets from unfinished narratives. 'Cosmic Disorder' (all works 2000), is a series of nine exuberant collages of coloured photocopies, oil paint and kitschy additions which hang off the sides or tops of unframed canvases. Porcelain swans, figurines and junk shop trinkets perch above the paintings like wordless titles, simultaneously joining and offsetting the work. Luxuriant colour abounds, and painted beads and baubles dangle like wind-chimes in a breezy Orientalism populated by maidens and patterned dreamscapes.

Flutter, a picture which gives the word 'playful' new meaning, is a peachy-red canvas with a rebus-like phrasing of images set against an elongated cloud. Two legs run as a pair, one male, in slacks, and the other bare, wearing a girlish pump. Painted, cartoonish faces float disconnectedly, a tongue licks a scoop of ice cream, and an Ottoman jug teeters dangerously close to a woman's head. Crammed with movement, the images recall Takashi Murakami's cartoon-like paintings and Nancy Spero's figuration. Curvaceous urns and ruffles crowd a corner, and the top of the canvas is lined in a dazzling array of pastel sparkly balls known and loved by every cat I've ever owned.

The pet motif reappears in Wind Disorders, which features the wet affection of stylised blue dogs licking young girls' faces and mouths, a cuddly bestiality reminiscent of Carolee Schneeman's collage of the artist French kissing her cat in numerous positions or, more darkly, Henry Fuseli's (The Nightmare) (1781), which depicts a gargoyle seducing a sleeping woman. Bramson's work is full of art historical quotations. Bouquets of Odilon Redon-esque flowers share a space with Indian beaded peacocks and black and white newsprint graphics in Combating Drowsiness, while the sensuality of Japanese woodcuts is alluded to in Decorum, an image of two traditionally dressed Oriental couples engaging in various degrees of foreplay. Ingres' Large Odalisque (1814), is revisited in Telling Tales in Winter, a painting dominated by an elongated woman's naked back, and a bare-breasted Arabian couple.

Bramson toys with imagery that is difficult and temptingly droll. She also makes use of other artists, purchasing paintings at 'starving artist sales', (awful discount affairs that hawk 'fine art' to match the sofa), before cutting them up and applying sections to her own canvases. It is nearly impossible to tell what's what, as the layers and groupings result in cohesive, seamless canvases.

Tactile adornments such as plastic grapes and ostrich feathers compete with decorative, painted embellishments: cobwebs, floral motifs, curlicues, and starlight. The only whisper of a frame is a retro one that contains only two sides of the Winter canvas. Traditional zones of sexuality, such as female legs or necks, are combined with seductive symbols such as pearls, eggs, and lush red mouths, along with all sorts of flora and fauna: orchids, roses, cherries, apples, and birds. Desire seems to seep from all the paintings.

For a long time Chicago's painters have been overshadowed by the legacy of its Imagist movement of the 1960s, which was dominated by humourless, cartoon-like figurative work. In the 1980s, Conceptualism took over, but Bramson's opulent sprawl has weathered both periods. Her whimsical canvases are nimble and her approach to collage remains fresh, an explosion of unselfconscious eroticism that captures storybook Surrealism in the twilight territory of adult play.