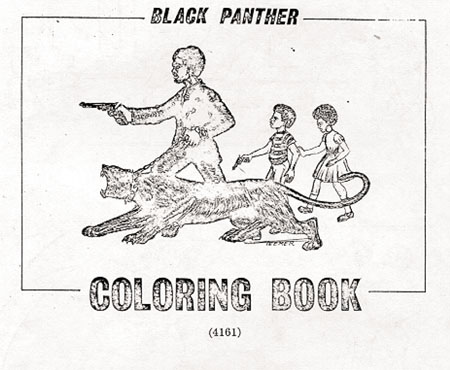

Picture Piece: The Black Panther Coloring Book

The aesthetics of Black Power

The aesthetics of Black Power

In the post-Twin Towers world, the barricade-cool appeal of 1960s ‘radical chic’ seems comfortingly wholesome. These days, along with Baader-Meinhof coffee table books and lucrative May 1968 nostalgia trips, Black Power imagery is more likely to be used to sell Jazz-Funk compilations than revolution. Yet, with its berets, shades and leathers, and Emory Douglas’ distinctive graphic emblems, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defence was, at its peak, a group acutely aware of its powerful public image.

In 1967, the US government’s covert agency COINTELPRO began a sustained campaign to undermine the activities of militant black nationalist organisations such as the Panthers. One prurient document that surfaced in the late 1960s was The Black Panther Coloring Book. Opinions differ as to its origins. One story goes that the FBI, concerned about the popularity of the Party’s Free Breakfast Programme for schools, designed the book and distributed it to shops and community organisations sympathetic to the Panthers. Another, more complex theory alleges that the book was created by an eager new party recruit, but was subsequently denounced as racist and too violent by the BPP before copies fell into COINTELPRO’s hands. The crude drawings depicting gun-toting children and wild pigs in police uniform would seem laughably crass if it weren’t for the needless loss of life incurred by both sides throughout the BPP’s troubled existence.

Here, one-time Black Panther Party leader Eldridge Cleaver poses with a sculpture made whilst serving time in prison following his return from self-imposed exile abroad. Up against the Panther’s high impact visuals, the significance of Cleaver’s sculpture – a strange hybrid of a Paul Thek ‘Meat Piece’ and an engine block covered in limpets – seems oddly indistinct. When the revolution comes, high Modernism will be no match for simple graphics and a sharp suit.