Pierre Soulages

Musée Soulages, Rodez, France

Musée Soulages, Rodez, France

Ninety-four years old and still active in his Paris studio, Pierre Soulages – the so-called ‘painter of black’ – has remained a star in Europe since his French debut in 1949. In 2001 he was the first living artist to have an exhibition in St Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum, in 2009, he was the subject of the Pompidou’s largest exhibition to date.

This year, on 30 May, President François Hollande travelled to Soulages’s native village of Rodez in southern France to inaugurate the long-anticipated Musée Soulages, funded by the Midi-Pyrénées regional council, the municipality of Aveyron and the French government. (Two donations made by the artist and his wife, comprising over 500 works, anchor the permanent collection.) Designed by Catalan architects RCR, this simple arrangement of Corten steel boxes merges with the surrounding landscape, while its sleek contours stand apart from Rodez’s 13th-century city centre. Perched on a hill like an exotic mushroom, the structure’s rust-streaked surfaces echo the traces of ochre and pink in the regional sandstone; cool, dark interiors of grey steel recall the province’s slate roofs.

Respect for the local environment has always informed Soulages’s work and – despite the international appeal of his large-scale canvases, works on paper and prints – he has regularly asserted the aesthetic influence of his provincial hometown, citing the austere architecture of the cathedral and its stark Romanesque facades. Born in 1919 on a street close to where the museum now stands, he was intrigued at a young age by artisanal craft. During a trip to the nearby Fenaille museum, he discovered menhirs –anthropomorphic stone monoliths etched in bas-relief that date from 3,500 – 2,300 BCE and are found throughout the Lacaune region – and has devoted much of his life to negotiating modern forms and crude materials.

The first installation of the museum’s permanent collection charts the development of that interest in various media, beginning with early landscape paintings from the 1930s. In Peinture 60 x 73 cm (Painting 60 x 73 cm, c. 1936), a small representation of trees on a sloping hillside, Soulages conspicuously eschews the lush and verdant, emphasizing instead the sear: wood and earth, dry branches cooked by the sun. Already, the largely self-taught artist was mediating between the abstract and the figurative, and using the branches of trees as a way to frame space.

In his ‘Brous de noix’ (Walnut Stains) series from the 1940s, Soulages eliminated representation altogether, placing fluid organic forms in conversation with geometric beams and grids, and opening windows onto the bare white of the supporting surface. This exploration of light, through contrast or transparency, would later come to fruition in his series of ‘Outrenoirs’, loosely translated as ‘Beyond Blacks’, which has occupied him since 1979. Works like Brou de noix 65.4 x 50.3 (Walnut Stain 65.4 x 50.3, 1948), in which architectural black bars appear silhouetted against a bright ground, draw positive and negative space into a physical tension that verges on sculptural.

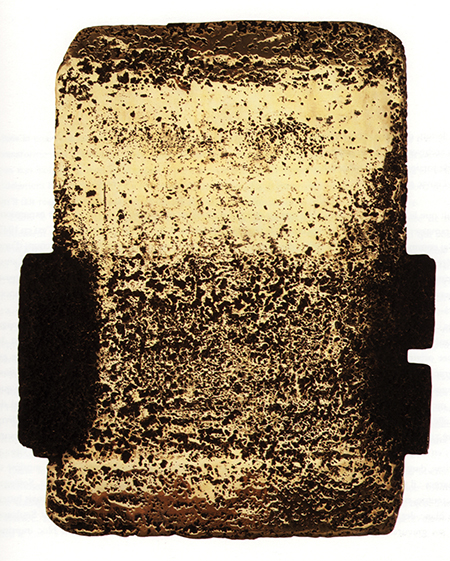

A similar manipulation of the flat surface is embodied in a striking selection of lithographs and aquatints presented in dark rooms along with their printing plates. Rendered in earth-toned blues, browns and sandy yellows, these abstract compositions have the spare, graphic quality of Japanese calligraphy and mottled surfaces that evoke raw stone. Both gestural and measured, they are occasionally translated into three dimensions as hanging bronze works, such as Bronze III (1977), which gleams against the wall like a plate of ancient armour.

By the end of the 1940s, Soulages returned to oil paint, but he abandoned the painter’s traditional tools for industrial materials such as rakes and rollers, which allowed him to adopt a more visceral relationship to the pigment. Black progressively dominated, leading eventually to the shimmering ‘Outrenoirs’, which feature exclusively black paint. Thirty of these towering canvases are shown as the museum’s inaugural temporary exhibition, and they demonstrate the range of the mark marking Soulages has pursued, as well as its surprisingly diverse effects. In some works, layers of thick black impasto are dragged across already hardened slats of paint, creating the appearance of modelled ridges and valleys or staggered tectonic plates whose edges curdle against one another like crashing waves. In Peinture 243 x 181 cm (Painting 243 x 181 cm, 2002), a triptych of horizontal canvases, violent strokes sweep down from the top right corner, evoking bolts of lightening; the black expanse of Peinture 162 x 181 cm (Painting 162 x 181 cm, 2004) seems to have been combed, and the light falls against it in gently white-peaked striations, while Peinture 162 x 724 cm (Painting 162 x 724 cm, 1986) could have been created with the tip of a pencil.

Throughout his life, Soulages has striven to eliminate excess from his work, attempting to access the most basic elements of perception: light and form. He has often declared that ‘black is light’ and his ‘Outrenoirs’ lend authority to that assertion. Deprived of distracting colours and subtly sculpted, these mono-pigmented canvases appear to have a luminous quality, shifting and blinking like windows in the sun.