Poet in Action

An interview with Alejandro Jodorowsky

An interview with Alejandro Jodorowsky

As inventor and grand exalted magus of the ‘midnight movie’ – a late-night cult phenomenon conceived at New York’s Elgin Theater with the release of El Topo (The Mole, 1970) and La Montaña Sagrada (Holy Mountain, 1973) – Alejandro Jodorowsky’s strange trip into renegade cinema has been narrated ad nauseam over the last 40 years. But Jodorowsky is much more than the sum of these two unlikely classics, and the context of the director/author/composer/psychologist’s career stretches far beyond the narrow era of counterculture to which he imparted a series of ineluctable, cinematic images.

Born in 1929 to Russian émigrés in the hinterlands of Chile, Jodorowsky, barely out of adolescence, abandoned his family for Paris, where he hoped to pursue his ambitions as a poet, scholar and mime. It was in the postwar metropolis that he encountered those patrician figures of an elder generation who would inspire him both into service and rebellion: Gaston Bachelard, André Breton, Maurice Chevalier and Marcel Marceau. Although he never had the opportunity to meet him, Jodorowsky’s greatest inspiration, Antonin Artaud, was the young provocateur’s second in his duel with European artistic conventions.

Returning to the Americas in the early 1960s, Jodorowsky discovered the work of Spanish author and playwright Fernando Arrabal, whose violent drama Fando y Lis (Fando and Lis, 1968) would be the subject of the fledgling filmmaker’s first feature – and, depending on whom you believe, the inception of a performance-art grift that Jodorowsky, Arrabal and the novelist Roland Topor jocosely designated the Panic Movement.

Jodorowsky’s reputation burned brightly and incinerated quickly, due in large part to his infamous quarrels with music impresario and film producer Allen Klein, whose refusal to distribute El Topo and La Montaña Sagrada for nearly 30 years killed many of Jodorowsky’s funding opportunities. By the time of Santa Sangre (Holy Blood, 1989), another, more prolific Jodorowsky – as scribe – had already risen to prominence. Having published several collections of short stories and comic strips since the mid-1960s, and without a viable project in the early 1990s, the filmmaker began an effusive regimen of writing, producing works on tarot, psychomagic (a form of Jungian and koan-inspired psychology) and Eastern philosophy, in addition to an impressive catalogue of science-fiction comics and graphic novels. Most of these texts remain untranslated into English, though the long-running series L’incal (The Incal, 1981–ongoing), conceived by Jodorowsky and the French illustrator Moebius, continues to receive plaudits for its singular contributions to the graphic-novel genre.

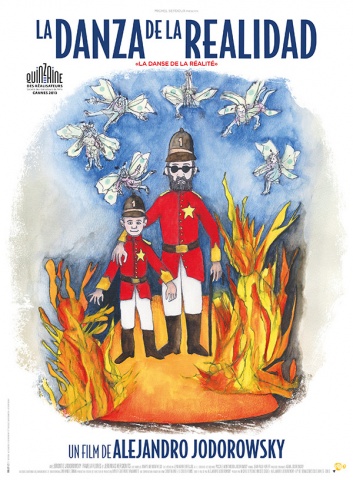

Published as a memoir in 2001, La danza de la realidad (The Dance of Reality) narrates the difficulties and whimsies of Jodorowsky’s youth in the town of Tocopilla; he would later use this text as the springboard for his overdue return to directing in 2013. Shortly before the film’s much anticipated screening at Cannes, Jodorowsky paused to discuss his life and work both on and off the screen.

Erik Morse You arrived in Paris from Chile in 1953 as an exile and an outsider. I have read that it was originally your work in the circus and pantomime in Santiago with the Teatro Mimico, a troupe of your own creation, which originally led you to Europe. Could you say something about your early fascination with mime?

Alejandro Jodorowsky I didn’t want to be an interpreter; that is to say to be an actor who repeats words that he hasn’t written. I wanted to be a creator: to express myself with my body and not with words. The only words that interested me were those of poetry, because they were proposing, tragically, to attempt to explain silence.

EM Despite the emphasis that is often placed on visuality in your films, the condition of silence – whether it be in Zen koans, meditation, catatonia or aphasia – is central to your work. Do you think we have forgotten the preciousness of silence?

AJ Spiritual silence does not eliminate noises but peels off from them. When I speak about silence in art, I speak about a spiritual, interior silence, a removal from the world, a living in the world without being of the world. Sounds and words are always like clouds that ambulate below the silence of an unaffected sky, always clear and blue.

EM You’ve said that, at the age of 15, you destroyed all of the photos you had of yourself in an effort to erase any memories of your life in Chile. I gather from your writing that your relationship with your father was very difficult. Did you recognize at this early age that you belonged to no family, no community, no country?

AJ I was born in a very small, industrial desert town called Tocopilla, lacking any culture. My parents were merchants, as without culture as my native town. I do not know why I was born a mutant. I came into the world with ten teeth and fair hair. I learned to read, suddenly, at the age of four. At the age of seven I had already read the classics, amongst them all the works of Shakespeare. That family of mediocre people, who were blind to art, was a prison for me. I erased them all from my life at the age of 23 – father, mother, sister, grandparents, uncles, cousins. I never saw them again.

EM What do you recall of the artistic environment of Paris in the early 1950s? The immediate postwar years in France are usually contextualized as a jumble of various art and political subcultures filling the void left by war and the rise of Gaullism.

AJ I arrived in Paris with three goals: to work with Marceau, to study philosophy at the Sorbonne with Bachelard and to frequent Breton’s Surrealist group. And I did all those things. I became Marceau’s principal assistant (I wrote many of his pantomimes), created the philosophy of the Panic Movement, and attended Surrealist meetings for two years, inventing games for them.

EM How did you see yourself in those years before you met Arrabal and Topor and conceived of the Panic Movement? Was it primarily as a performer? An artist? A philosopher? A flâneur?

AJ What was I? I was a poet in action. I knew (or believed) that I had much more imagination than Salvador Dalí.

EM I’ve read that you also directed Chevalier during his theatrical comeback in the late 1950s. At that time, Chevalier had been reduced from a star to a traitor and criminal. Was there anything you learned from his cabaret musical style that influenced your more radical theatrical and cinematic vision?

AJ From Chevalier I only learned not to be greedy. That diva was sickened by avarice. I created a year-long stage revue for him, but it was difficult to get him to pay my salary. As for learning, he learned from me, because I taught him the art of pantomime, an art that he subsequently used in all of his tours.

EM You mentioned that you attended Bachelard’s final lectures at the Sorbonne. What were your impressions of his books on the elements and his general interest in psychology and shamanism?

AJ The book that most impressed me and forever left its mark on my mind was one of his least known: The Philosophy of No (1968). Through it, I learned to think correctly. Bachelard was one of the first professors to discover non-Aristotelian semantics. Today we would call this quantum thought.

EM The Panic Movement owes much of its conceptual and theatrical development to Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty. In fact, in an essay titled ‘The Goal of Theatre’ (1966), you write: ‘The Theatre should be based on what has until now been called “mistakes”: ephemeral accidents […] The Theatre […] should not last even a single day in a man’s life.’ How did Artaud’s work influence your oeuvre, from panic to film to tarot and psychologic?

AJ Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty filled me with enthusiasm only until I stopped searching for catharsis through cruelty and began searching for healing through kindness.

EM Do you think perhaps too much emphasis has been placed on the Artaud connection when your theatre and film works are just as inspired by Buster Keaton and Luis Buñuel? Where do you think this fascination with Artaud comes from?

AJ I am not interested in the fascinations of armchair philosophers, of people who warm office chairs with their asses. Everyone has a different vision of famous people. Your Keaton, your Artaud, are neither my Keaton nor my Artaud, nor are they the Keaton or Artaud of others. Every time that someone uses a plump woman with big bosoms in a movie, the critics say, ‘It’s Fellini-esque’. If we use a dwarf, people will say, ‘It’s Buñuel-esque’. If we use monsters people will say, ‘It’s Tod Browning-esque’. But the fat women, the dwarfs, the monsters can be absolutely Jodorowskian. I am a mutant – the only one that has inspired me is the immense black toad that lives in my soul.

EM The only evidence we have of the Panic Movement is a May 1965 video of an event titled Melodrama Sacramental. Can you briefly describe its central tenets? Is panic meant to be a confrontational and provocative act, a youthful rebellion designed to destroy the ego, or is it also meant to be a kind of theatrical therapy used to heal or calm in the manner of psychologic?

AJ Panic never existed as an organized movement with a manifesto, like Surrealism. Three artists with intense characters came together – Topor, Arrabal and myself – and we decided to make fun of culture, inventing the existence of something nonexistent. We would name any of the works that we were creating ‘Panic’; but separately, never together. In this way, fooling the critics, we would achieve something that without any definition would become a part of art history. And we achieved it.

EM I would like to hear about your first encounters with Arrabal. It seems that a collaborative spirit was unleashed that affected both of your careers tremendously. Did you immediately see in one another some kind of an artistic or spiritual brotherhood or was this a result of years of working together?

AJ When I was in Mexico, I mounted his stage play Fando y Lis, then, in my way, I turned it into a movie. Later, we were both in Paris. I adore dwarfs so I loved meeting him; he was of very small stature. In those days they didn’t have sex-shops in Paris. For me, pornographic photos were an art form. I had a big collection. Since they had given me an apartment in Paris with a large tub, I invited Arrabal to come for a bath. He did so. I handed him the pornographic photos. He said he was going to masturbate (at this time he wasn’t penetrating his wife, only masturbating with her because he believed that copulation would rob him of his creative power). And he did so, shut off in the bathroom. He came out with four of the books stained by jets of semen. This washis dedication. We never worked together nor did we influence each other. Each of us was faithful to his own style of creation.

EM You subcribe to psychomagic, an experimental form of performative psychology, but you still maintain a very traditional link to Jungian archetypes, myths and the family tree. Beginning in the 1950s, however, the anti-psychiatry movement, which grew from the same lineage of artists and theorists, has rejected this reliance on totemic imagery and sexual narratives – of the father and mother – as central to the formation of the subject. Do you think there is danger in a psychiatry that attempts to eradicate the traditional therapeutic role of the ‘unconscious’, and also searches beyond the family unit for the patient’s ego formation?

AJ Why ask me such academic questions? The language that you use, the scholarship that you exhibit, is a form of cultural idiocy. Jung tires me. He learned everything, he suspected it all, brought attention to the transpersonal, to the collective unconscious, to the ‘we’, but he remained locked in his elephantine ego. He was able to see the Buddha, but was incapable of becoming a Buddha. He spoke of alchemy without ever turning a piece of lead into gold. I give him the title ‘Tourist of Mysticism’. Psychoanalysis was created by doctors, men overfull with science, rigid intellects on the hunt for the chaotic language of dreams in order to translate it into a rational language. In Freud’s naiveté, blinded by his ego, he intended to explain dreams and put into words an unconsciousness that is expressed not in words but in rainbows. I could create psychomagic because I’ve been an artist since the age of five. I did the opposite of psychoanalysis: I taught our rational island to speak the language of the unconscious, to conceive of reality as if it were a dream, to get inside the dream by spitting butterflies and not words.

EM Throughout your artistic career, you have aspired to the disciplinary structure of artists like Leonardo, Petrarch or Jean Cocteau, as a sort of ‘Renaissance man’ – author, graphic novelist, filmmaker, playwright, director, spiritualist, psychiatrist. Why do you believe the modern art world disapproves so strongly of artists who attempt to expand their primary oeuvre to many genres or disciplines?

AJ Art is by no means one ‘artistic career’. A great artist does not use ‘disciplinary structures’. A true artist shits on the idea of being a ‘Renaissance man’. If you have testicles no larger than a walnut, you can only run behind a single rabbit. But if, like me, you have three or four testicles the size of melons you can run behind 30 rabbits at once and hunt all of them. I was ahead of my time by 30 years. In the 20th century, an artist devoted himself like a slave to one label: a ‘painter’ could not be a ‘writer’ or a ‘dancer’ or a ‘shaman’. Things in the 21st century have changed. Before, a phone was only a phone. Now what was just a phone is a device that photographs, plays music, sends texts, knows the weather, gives us directions. Soon it will be a vibrator and throw poisonous darts. Why, then, can’t an artist be countless things?

EM Between your fascination with medieval traditions like alchemy, tarot and the Borgias and your long-documented work with science-fiction in the graphic novel, you are constantly ‘time travelling’ between the distant past and distant future for inspiration. Do you think of yourself as belonging at all to the present moment? Is being rooted in the present important for you?

AJ At all times the past and the future exist in our present. But to live this you have to have a brain free of limits imposed by family, society and culture. Many live only in the past, blind and terrified, and do not want to see the future. They barely manage to live in a fragment of the present. What else can I say? Whenever I go out on the street, I see it full of the living dead moving about without going anywhere.

EM When you were recently asked which of your films remained your favourite, you answered Santa Sangre. This was a wonderful surprise because of the devotion shown toward films like Fando y Lis, El Topo and La Montaña Sagrada. It is also my favourite. Can you tell me about the film’s origin and the history of Gregorio Cárdenas Hernández?

AJ Don’t make me tell you the story of Goyo Cárdenas, the Mexican assassin! He was declared ‘cured’ following ten years of incarceration in a mental hospital, after murdering many women, then graduated as a lawyer, wrote novels, married and had several daughters. I met him one day at the café of a periodical we both worked at. I loved speaking with an ex-serial killer. I asked him what he felt. He told me that he remembered nothing, that he was now a normal and very good man. He felt redeemed. Then I thought: if this man, who has strangled many female victims, has forgotten everything, lives a quiet life and is well respected, this criminal society in which I live, this dirty, cruel and shameful period of human history, can be forgotten, thrown into the rubbish-filled waste bin of history: MURDEROUS HUMANITY CAN BE REDEEMED! From my meeting with him, Santa Sangre was born.

EM The Dance of Reality is your first feature in over 20 years. However, fans of your films have followed the rumours of mysterious projects like Abel Cain, Sons of El Topo and King Shot with purported collaborators including David Lynch, Marilyn Manson and Johnny Depp. No doubt the Dune adaptation – on which you famously began production in 1974 with collaborators including Moebius and H.R. Giger, Orson Welles and Dalí – is the most famous of these aborted attempts. Do you look at these ‘failed’ works as a necessary part/effect of your process and your uncompromising cinematic perspective?

AJ Everything is for the best. If I did not make a film in 20 years, I never stopped being a filmmaker – that is to say, a poet. All the previous projects were a preparation that made me what I am today. The universe is in continual expansion, like the mind of an artist. If I didn’t film those earlier projects, it’s because I should not have filmed them. They were not aborted, they were grand seeds. The Dance of Reality is definitively the best of my previous films, but it’s not better than my next films.

EM Can you tell me a little bit about the process of filming The Dance of Reality? It seems shrouded in secrecy at the moment. We know only a few things: it is based on your autobiography of the same name that focuses mostly on your childhood; it is financed by a handful of wealthy patrons; it was filmed in a village near your hometown of Tocopilla; and it stars most of your sons. Does the movie hew close to the book or was that only used as a rough blueprint during filming?

AJ I obtained enough money to produce a film so that losing money doesn’t matter. I’m an artist, not an employee of Hollywood. No producer comes to me to tell me what I can or cannot film. I don’t use subliminal political propaganda, nor do I use subliminal propaganda for commercial products. I don’t address an audience of buyers, nor am I interested in how idiots or infantilized adults will react. I don’t do advanced publicity, nor do I allow a ‘making-of’ film; I prohibit photos or videos during the filming. I don’t say anything. Children gestate in the darkness of their mother’s womb, I have no reason for bringing my foetus to light before its proper time. The movie is finished. I assure you: it’s a masterpiece.

EM What was your experience of revisiting Tocopilla after all these years? I read that locals dubbed you ‘Mayor Jodorowsky’ because you practically rebuilt the town for the shoot.

AJ I only had to rebuild my house, because it had burned down. Tocopilla is almost a ghost town. It has about 30,000 inhabitants, who go to neighbouring cities for work. Nothing has changed in 80 years. There is not a single new building. I found Tocopilla exactly as I knew it as a child. All the Tocopillans collaborated on my film. In the next month, I’m trying to do the official premiere of The Dance of Reality in Tocopilla, even though the town only has two very small hotels that can host no more than 50 people. The guests will have to sleep in tents.

EM Was the filming of The Dance of Reality and the return to Tocopilla a ritual of healing for you after renouncing your name as a 15-year-old so long ago?

AJ That’s right. Just like you said it.

EM With films like Santa Sangre and Tusk (1980), you’ve dealt with the subjects of childhood and memory and immersed us in the world experience of the child. Can you explain that special psycho-logical or fantastical connection that exists between a child’s eyes and the movie screen?

AJ We all keep in our souls a secret child. This ‘special psychological or fantastical connection that exists between a child’s eyes and the movie screen’ is the same that everyday, moment to moment, exists in our everyday. There is no adult in this society who is not a child who suffers from not living in the ideal world that he longs for.

EM It’s also been rumoured that you will begin production on Sons of El Topo, the long-awaited sequel to El Topo? Do you foresee a day when you will retire from filmmaking?

AJ I have returned to the cinema. I am surely going to continue. I am shuffling several projects, waiting for the magic of circumstances, that divine synchronicity, to reveal which one I should produce. The Children of El Topo? Juan Solo? Albino and the Dog-Men? The continuation of The Dance of the Reality? I still don’t know.

Translated by Erik Morse and Veronica Gonzalez-Peña. Veronica Gonzalez-Peña’s latest novel, The Sad Passions (2013), is published by Semiotext(e).