Politics, Slogan Clothing and Pop Culture: A Brief History of Melania Trump’s Jacket

Decoding the First Lady’s off-brand fashion choice

Decoding the First Lady’s off-brand fashion choice

In January 1961, a week before John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, it was announced that Oleg Cassini would be the sole designer for the imminent First Lady. As reported in Women’s Wear Daily, Cassini told the press they were on the threshold of a ‘new American elegance’ thanks to Jackie Kennedy’s ‘beauty, naturalness, understatement, exposure and symbolism.’

It’s not unusual for American politicians to send political messages through their clothing. Barack Obama often wore suits by Brooklyn-based tailor Martin Greenfield, signifying his support of US industry and jobs. As Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright used brooches to communicate diplomatic intentions. Donald Trump wears the Make America Great Again (MAGA) slogan on his cap. But the First Lady occupies a particular place in American politics where the symbolism of dress takes on a heightened role, becoming a form of diplomacy on a global and domestic stage. This is so embedded into American culture that the Smithsonian National Museum of American History has been adding to their First Ladies Collection for more than a century, asking each First Lady to donate a garment that represents them.

So how do we read Melania Trump’s decision to wear a Zara jacket emblazoned with ‘I really don’t care. Do U?’ while travelling to and from a child detention centre in Texas? The First Lady’s unannounced visit came in the wake of the family separation scandal that has engulfed American politics, and which culminated with the President signing an executive order to end the enforced separations which were a direct result of the administration’s ‘zero tolerance’ immigration policy. Trump’s communications director, Stephanie Grisham, reportedly said: ‘It’s a jacket. There was no hidden message. After today’s important visit to Texas, I hope the media isn’t going to choose to focus on her wardrobe.’

The focus on the clothing of women in public life is indeed a gendered issue. One which speaks to the fact that historically women had scarce alternative means of public expression. But it is disingenuous to suggest that the First Lady’s wardrobe is not primarily about communication, and the current inhabitants of the White House understand this just as well as previous administrations have. In many ways the jacket is a perfect example of Trumpian doublespeak: boldly proclaiming a message while telling those that focus on the message that they are wrong to do so.

There is often an ambiguity in interpreting dress and using words adds clarity. Text anchors meaning in a way that cut or fabrication can’t, turning the polysemic codes of clothing into an unequivocal statement. The jacket loudly declared a very different message from the one Melania Trump spoke when she asked how she could ‘help these children to reunite with their families as quickly as possible.’ The jacket instead signalled a lack of empathy as a political stance in itself, in Rebecca Solnit’s words, ‘a politics of disconnection.’ The flippancy of the remark is unprecedented in First Lady dressing, a position which (largely due to outdated gender codes) is intended to symbolize compassion in any given administration.

To wear a USD$39 Zara jacket is off-brand for Melania Trump. Her usual fashion choices tend towards the formal – with a penchant for European luxury labels which sits at odds with the administration’s America First focus on US manufacturing. In this she differs from her predecessor. Michelle Obama was credited with democratizing the First Lady wardrobe by mixing brands such as J.Crew and the Gap with established and up-and-coming American-based designers from Calvin Klein to Thakoon and Jason Wu.

Political slogans, however, are very much Team Trump. The incandescent red of Trump’s MAGA cap ensured that slogan clothing was a key part of the presidential campaign. Associated with the counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s, slogan dressing is redolent of rebellion and was used to challenge the establishment rather than uphold the status quo. This notion chimes with Trump’s nativist brand of ‘drain the swamp’ populism. As a stand against the mainstream or to show allegiance to a particular group, slogan T-shirts have history on both sides of the political divide. A 1973 New York Times article titled, ‘The T-Shirt Has Become the Medium for a Message’ featured Watergate-inspired shirts with slogans such as ‘I'm Democrat, Don't Bug Me.’

The T-shirt as sartorial activism reached a crescendo when designer Katharine Hamnett met Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher at a Downing Street reception in 1984 emblazoned with the anti-nuclear statement ‘58% DON’T WANT PERSHING’ (referring to the proliferation of US Pershing nuclear missiles across Europe). Using simple, bold text Hamnett’s T-shirts are designed to be read from far away and decipherable even in small photographs, imitating the tactics of tabloid headlines. Her current designs include ‘Cancel Brexit’, and she repurposed her original ‘Choose Life’ T-shirt as ‘Choose Love’ for the charity Help Refugees. Women’s Marches, Black Lives Matter and the Time’s Up movement all have related merchandise, which is a useful tool for expressing solidarity and raising awareness, but has at times been criticized for marketizing activism.

With politics more polarized than it has been in decades, it’s unsurprising that slogan T-shirts have been embraced as a trend. But issues arise when politics and activism intersect with fashion, which can result in the luxury market commodifying the aesthetics of protest (see Karl Lagerfeld co-opting feminism for a Chanel catwalk finale), and high street stores using text to fetishize the working class experience, a move that has been branded ‘poverty chic’.

Three years after Hamnett wore her anti-nuclear T-shirt to Downing Street, the magazine Smash Hits published an interview with Margaret Thatcher. ‘Some of the kindest people have the most strange appearance,’ Thatcher said. ‘You can't tell their politics by what they look like. You might be able to tell by what they've got printed on their T-shirt but not by what they look like.’ Until last week, this was arguably the most unlikely Venn diagram of politics, slogan clothing and popular culture. In denying there’s any hidden meaning to her jacket, we should take the First Lady’s declaration at face value.

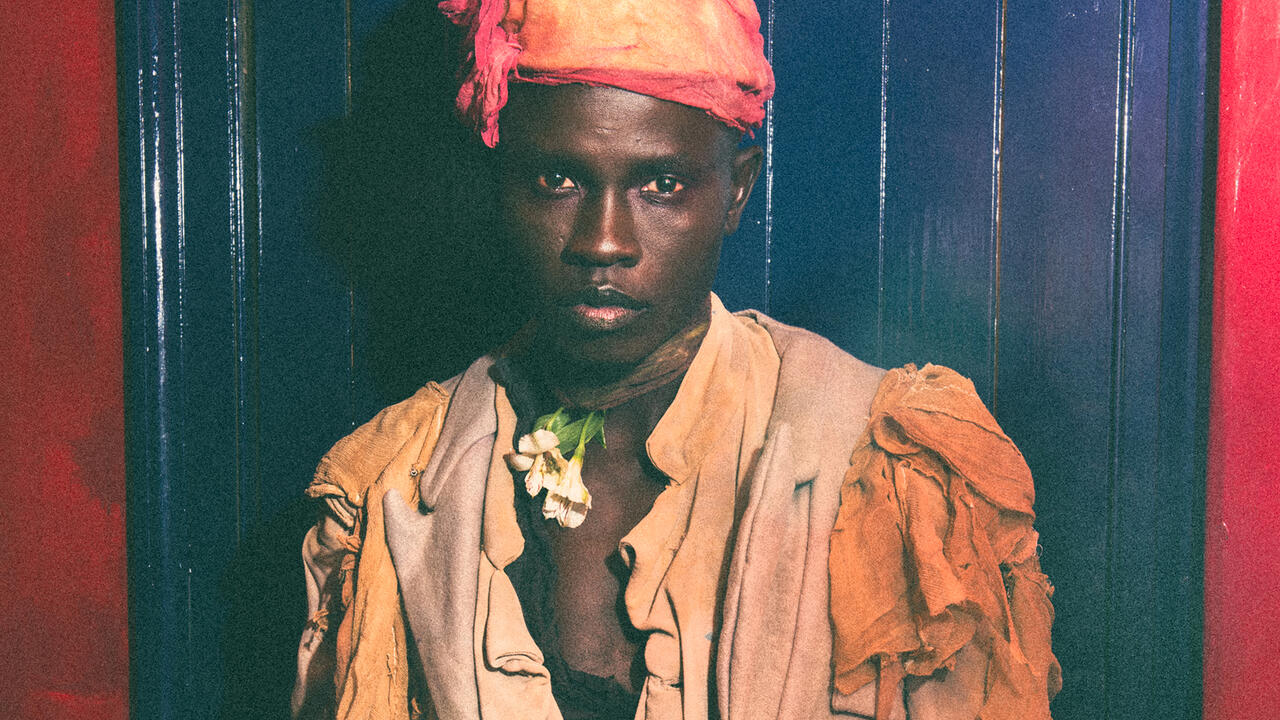

Main image: US first lady Melania Trump boards an Air Force plane at Joint Base Andrews, Maryland, travelling to Texas to visit facilities that house and care for children taken from their parents at the US-Mexico border, 21 June, 2018. Courtesy: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images