Robert Morris

A mini retrospective at Sprüth Magers, Berlin, shows the artist was never the cut-and-dried Minimalist of legend

A mini retrospective at Sprüth Magers, Berlin, shows the artist was never the cut-and-dried Minimalist of legend

When Michael Fried, in his essay ‘Art and Objecthood’ (1967), disparaged Minimal Art’s promiscuous ‘theatricality’ and its erosion of Modernist autonomy, he cannot have known the extent to which the recontextualization and re-creation of contemporary art objects would make that erosion the rule rather than the exception. A mini-retrospective of Robert Morris’s work at Sprüth Magers in Berlin made it clear that art’s passivity to a viewer’s interaction is now part of a larger passivity to the context in which it is displayed and trafficked.

As has been common practice since they were first exhibited, Morris’s mid-1960s plywood sculptures were recreated here according to his original specifications. These re-fabrications are not seen as editions or as copies of an original, but as equal manifestations of a sculptural concept. Floor Piece (Bench) (1964) is a 7.5-metre-long plywood block with one of its long upper edges bevelled to a curve, and sealed in the same yellowish mid-grey emulsion that coated all the 1960s works in the show. Rather than a generic neutral grey, the shade suggests aestheticized interior design, conferring on these objects the replicant aura of ghosts of a lost specificity. What Donald Judd called ‘specific objects’ prove to be only as specific as a set of measurements and a number on an RAL colour chart – that is, not objects, but ideas for objects.

That aura was heightened by a gallery which implicitly asks Morris’s art to function as a precursor of the work of younger artists who have exhibited here, whose art is pitched as a subversion of what Fried described as Minimal Art’s ‘risk [...] of seeing works of art as nothing more than objects’. Last year, for example, Sterling Ruby showed plywood benches graffitied with spraypaint – a dressing of Morris’s neutral forms in the tattooed skin of pop culture and an attempt to evoke what Bruce Hainley has called ‘the private life of Minimalism’. Consequently, Morris’s grey semi-originals displayed in the same space acquired the air of inverted déjà vu, as though they recalled what they themselves have spawned.

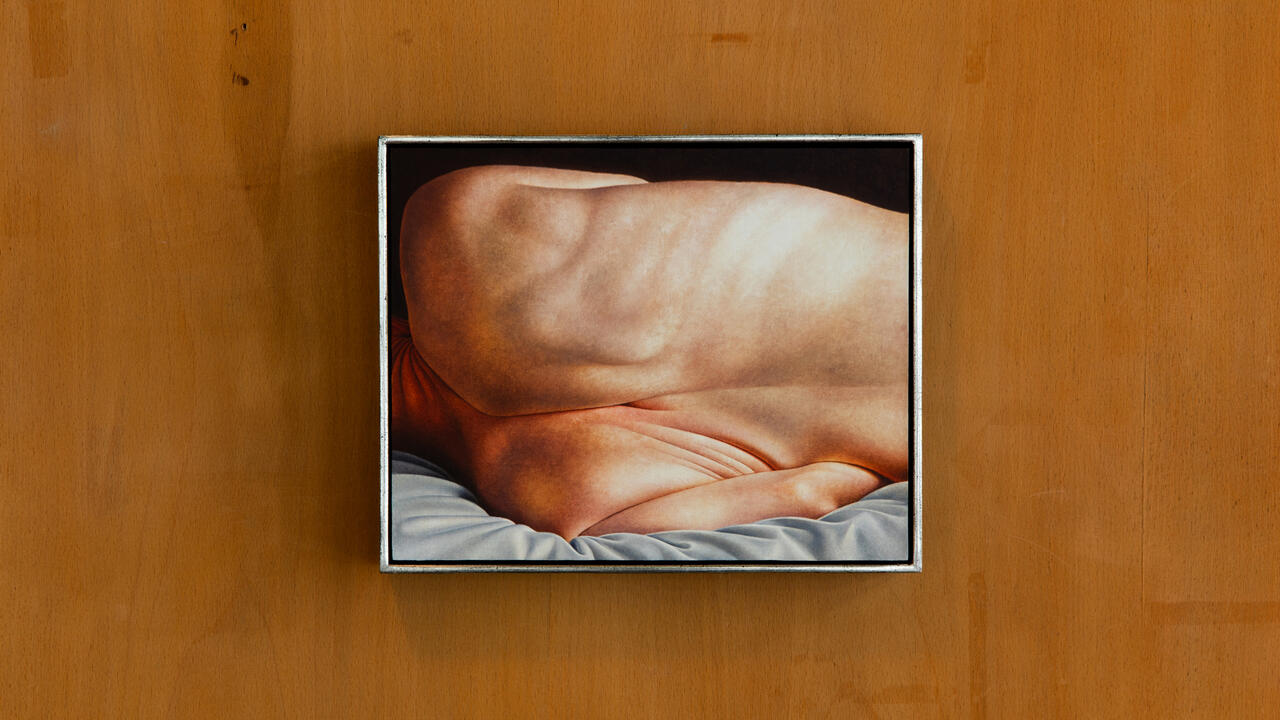

But Morris was never the cut-and-dried Minimalist of legend or the reliable purveyor of non-referential boxes that neatly confirm the revisionist narratives of artists like Ruby. Rather, he predated their critiques, conflating phenomenological materialism with the Freudian unconscious. Seen in overview, his career is characterized by its resistance to being reduced to any single narrative, whether empirical, political or formalist. Untitled (Ring with Light) (1965/6), like a mammoth grey Polo mint that has been surgically bisected, reveals an inner light that might be directing a beam of the finest critical irony in the direction of Fried’s yearning for Modernism’s air of harbouring secrets it couldn’t bring itself to impart. (Fried, however, interpreted the work’s intimation of ‘an inner, even secret, life’ as an example of the ‘anthropomorphism’ he found objectionable in Minimal Art.) Even the hanging felt work Untitled (1976), one of a series with a reputation for the purest materialistic exposition, is an oblique sexual metaphor. Fabric peels back, like the petals of a great black flower, to reveal a narrow vertical slit.

Scatter Piece (1968), a chaos of metal and felt off-cuts, is the entropic disintegration of these formal geometries and the most radical manifestation of Morris’s challenge to the viewer to project order onto dumb material. The fragments themselves are relatively recent – produced for a 1980s presentation – so his gambit now asks us to register them as ‘specific objects’ and not approximating cyphers. This was always the trajectory of Morris’s method: to intimate the unfathomable nature of interpretation required by even the most rudimentary of forms, and ask the viewer to plumb its depths. It is a challenge that can make his art seem manipulative, as though we were puppets tugged to and fro on a stage of his devising. The sound installation Voice (1973–4), for instance, comprises eight door-sized speakers in a windowless room, each seeping a male voice’s stream of consciousness. Narratives merge as the viewer drifts into the orbit of one speaker after another. The installation claims the room as a metaphor for the dimensions of a mind inundated by a torrent of inchoate thoughts. The box speakers are Minimalist objects with an audio component, like Morris’s earlier Box with the Sound of its own Making (1961), which denies their present-tense singularity by implying the past in which it was recorded. Paradoxically, this resembles the back-to-the-future air of temporal displacement that the gallery context foists upon Morris’s work: perhaps we should see him as capable of wresting a passivity to the manipulations of context, and converting it into positive content. The reconstructed work’s spooky aura of bucking natural historical sequence may well be his intention.

This fertile tension between ideally centred perception and its entropy – through psychic dissolution or the atomizing of mediation – was conspicuously diffused in recent pieces. A circle of eight children’s chairs (Chairs, 2001), each covered by a sheet of crumpled lead, seemed a sentimentalized outpouring of the repression glimpsed though the geometric interstices of the earlier work. In order to become present, the elusive materiality of Morris’s work from the 1960s and ’70s has had to re-emerge on the other side of his imitators and detractors, only to find the present is a place in which it is as corrupted for him as it is for them.